High-quality bonds should hold up better than stocks, right? Particularly if defaults aren’t really the worry.

But that hasn’t been the case lately for debt issued by many Fortune 500 companies, a sector hit notably hard since the Federal Reserve shifted its stance to urgently cool inflation.

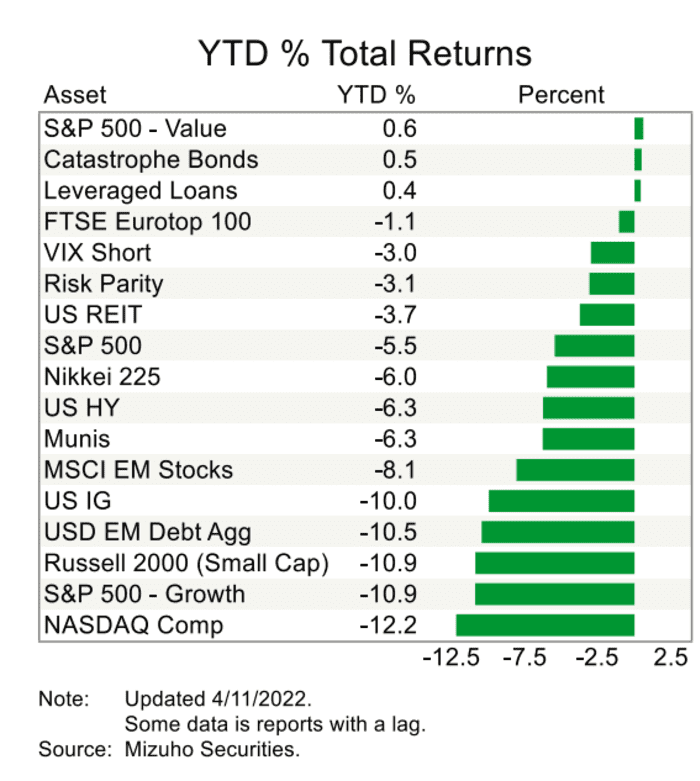

U.S. investment-grade corporate bonds, the debt sold by many big companies in the S&P 500 index SPX, +1.12%, have registered a negative-10% total return so far in 2022 (see chart), after booking their worst quarterly loss since the global financial crisis, according to Mizuho.

The rout in high-quality corporate bonds compares with a roughly minus-6% total return for the S&P 500 index SPX, +1.12% and negative-6% performance for bonds issued by municipalities and high-yield companies.

“We are in a tough environment,” said Jack McIntyre, a portfolio manager at Brandywine Global Asset Management. “Bonds are selling off, equities are selling off. The real return on cash is negative.”

McIntyre expects bonds to be a “great buy” at some point, given the steady march higher in yields, even though he expects bumps along the way.

For one thing, the Fed needs to figure out how much to increase its policy rate to help tamp down inflation that’s at 40-year highs, while also shrinking its nearly $9 trillion balance sheet, all without hurting the economy.

The rout in high-quality corporate bonds compares with a roughly minus-6% total return for the S&P 500 index SPX, +1.12% and negative-6% performance for bonds issued by municipalities and high-yield companies.

“We are in a tough environment,” said Jack McIntyre, a portfolio manager at Brandywine Global Asset Management. “Bonds are selling off, equities are selling off. The real return on cash is negative.”

McIntyre expects bonds to be a “great buy” at some point, given the steady march higher in yields, even though he expects bumps along the way.

For one thing, the Fed needs to figure out how much to increase its policy rate to help tamp down inflation that’s at 40-year highs, while also shrinking its nearly $9 trillion balance sheet, all without hurting the economy.