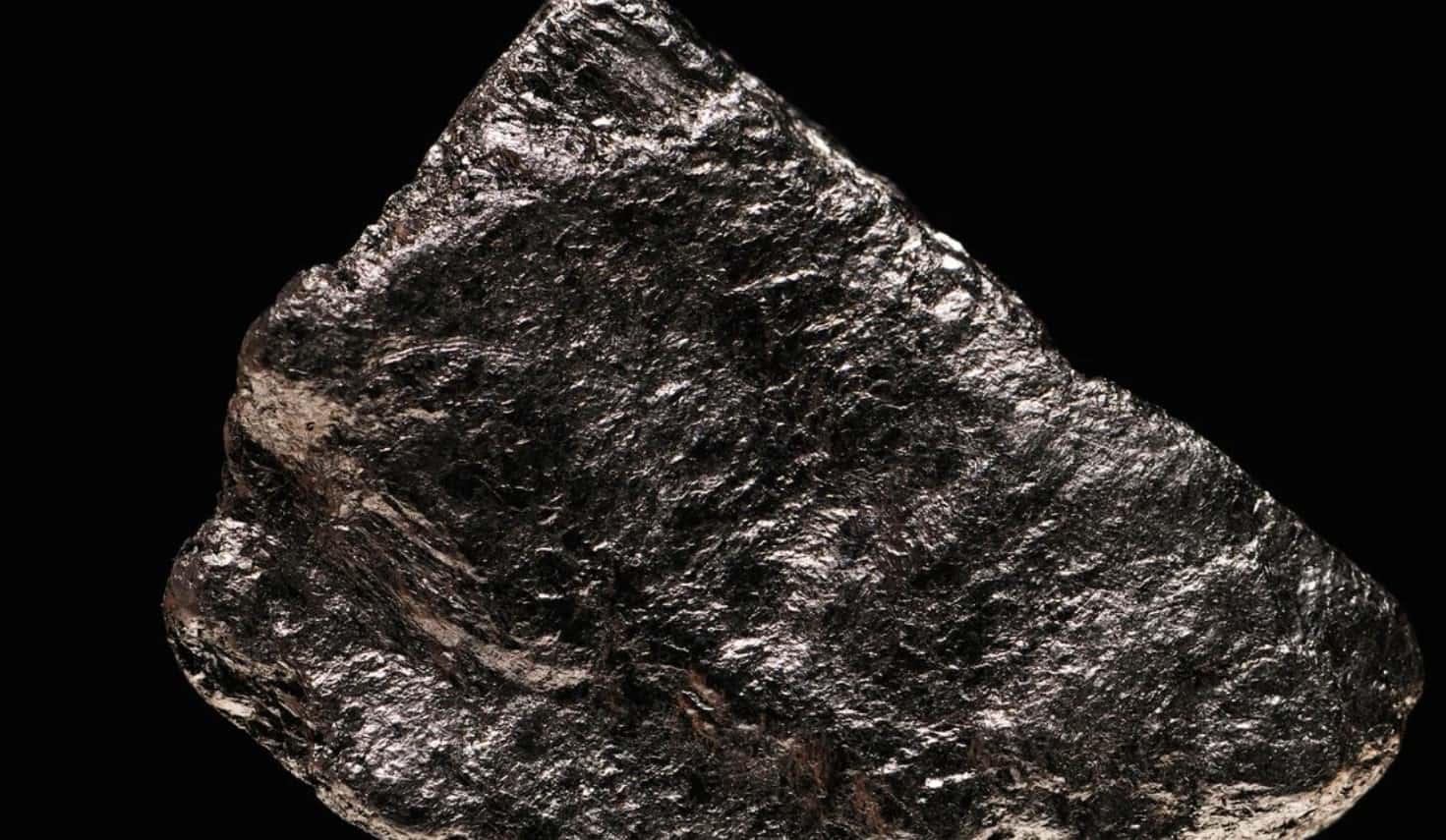

THE LACK OF a US supply chain for electric vehicle battery materials is often spun as a tale of inconvenient geography. In many ways, this is true. There’s cobalt from the Congo. Indonesian nickel. Latin American lithium. But there’s one critical material for which this isn’t the case: graphite. The material, which is the biggest component of battery cells by weight, isn’t a rare metal. It’s an arrangement of six carbon atoms that can be dug up basically anywhere in the world, including from large deposits in the United States and Canada. And where it isn’t found naturally, it can be made synthetically, usually from waste petroleum products. For long-lasting EV batteries, this approach is usually thought to be the best.

And yet, of all the critical materials that go into batteries, including those geographically constrained metals, the US is perhaps least equipped to produce its own EV-quality graphite. In fact, all of it is produced by China. Last year, when the federal government considered letting exemptions for tariffs on Chinese graphite products expire, domestic automakers (including Tesla) fiercely protested. There was nowhere else to get it—not because the US couldn’t source its own material, but because it simply had not invested in doing so.

It is, by now, no longer surprising that China leads on EVs. The country not only dominates in terms of sales—half of last year’s total sold in China—but, critically, in production. Backed by aggressive government policies, Chinese investors have spent the last decade building up the ability to extract raw materials and refine and assemble them into the large mighty batteries that power electrified vehicles. They’re set to cash in: The EV market is projected to bring in $9 trillion between now and 2030, according to a recent report from the research group Bloomberg New Energy Finance, and only grow from there.

Now American policymakers want in on the action. The Inflation Reduction Act, which passed through Congress last week and will likely reach President Joe Biden’s desk in the coming days, contains new subsidies for US drivers who want to buy an EV. It does away with an old program that capped tax credits at 200,000 per automaker. But there are also new conditions. Earning the full credit depends on the particulars of the car. Qualifying vehicles have to be manufactured in North America, and be made up, at least in part, of raw materials that are extracted and processed, and then refined and assembled into batteries, either in the US or in countries with which the US has friendly trade relations. (In other words: not in China.) The bill amounts to a sweeping attempt to stand up a US-led supply chain for the next generation of vehicles.

That’s gonna be tough. The legislation’s particulars could still change before it’s signed, and the Internal Revenue Service will ultimately determine which vehicles (and their supply chains) qualify for the credits. But the Alliance For Automotive Innovation, a trade group that represents most global automakers in Washington, says the current stringent rules will disqualify 70 percent of the EVs currently on the US market. An analysis of the bill by the Congressional Budget Office projects just 11,000 vehicles would receive the full credit in 2023.

Some argue that’s not such a bad thing. In an environment where the supply is crunched and many EV buyers face daunting waitlists, proponents of the restrictions say the country no longer needs tools like tax credits to convince people to buy battery-powered cars. Instead, the subsidies are an ambitious bid to change how automakers build them. Coupled with investments in critical materials producers through Biden’s invocation of the Defense Production Act, last year’s infrastructure bill, and last month’s bill to stimulate a domestic semiconductor industry, some hope that sufficiently aggressive policies can get the supply chains to a point where automakers and other battery end-users are willing to make all their stuff in the US, or at least US-friendly countries. The US is doing industrial policy, basically—matching what China did years earlier.

“This could be the US moment, where now there’s a guaranteed EV market,” says Kwasi Ampofo, who heads up metals and mining research at Bloomberg New Energy Finance. “This could potentially be a game changer, in the sense that it empowers US companies and US battery manufacturers to invest.”

Still, it isn’t going to be easy. The auto industry has made strides to produce battery cells and packs within the United States and closer to EV factories—a step that will help them qualify for half of the credits proposed in the IRA. But resource extraction and processing remain major gaps in the earlier stages of the supply chain. They will be hard to plug up quickly. “They build the cells here now, but they still build everything for the cells in China. So it’s just shifted the burden up one layer,” says Chris Burns, a former Tesla engineer and CEO of Novonix, which is building a plant to produce synthetic graphite in Tennessee.

While the share of domestic materials required to qualify for a tax credit in the Senate plan appears high—and indeed is—it is not theoretically impossible, analysts say. The US could have a domestic-ish EV industry, but it doesn’t yet.

Graphite is emblematic of the challenges. While the resources and technology to produce graphite are abundant, costs are typically higher for US processors than their Chinese counterparts because energy is more expensive and their operations are typically smaller and less efficient. Plus, there are environmental costs to graphite refining, which traditionally involves heating the material to extreme temperatures in open pits. Some companies, especially in Europe and the US, are trying cleaner methods that work at lower temperatures, in part because of local environmental regulations and in part to make their products more appealing to automakers concerned about their environmental footprints. But those processes are more expensive to scale up.

The next barriers for would-be graphite entrepreneurs are finding investment and securing agreements to sell their materials to EV makers. It’s a classic chicken-and-egg problem: EV-grade graphite requires more processing to ensure the material is safe and long-lasting enough to power cars for hundreds of thousands of miles, and each step along the supply chain requires qualification from automakers. More established Chinese firms already have those qualifications and buyers lined up, while newer graphite companies like Novonix need to prove themselves to customers while at the same time courting investors to expand their operations.

“It’s been a grind,” says Anthony Huston, CEO of Graphite One, a company that has been planning for 10 years to dig for graphite at a site in western Alaska that is believed to be North America’s largest known deposit. But that’s beginning to change, he says. The company has applied for grants included in the infrastructure bill that he hopes will act as a signal for automakers to invest in US suppliers. “What I think automakers are looking for is where the US government decides to dole out these grants,” he says. “They don’t want to get too far ahead of themselves.”

Automakers, for their part, are already in the early stages of reordering their supply chains, and the Alliance for Automotive Innovation says they’ve already spent more than $100 billion in the effort. For example: Tesla has struck agreements with Australia-based graphite producer Syrah Resources, which sources raw graphite from a mine in Mozambique and processes the material in Louisiana. The company received a $100 million loan from the US Department of Energy last month. General Motors has signed deals to secure lithium in southern California, cathode materials in Canada and Korea, and cobalt in Australia.

For the most part, automakers seemed pleased with their new tax credits, along with the other EV-friendly subsidies contained in the bill. Statements from Ford and General Motors officials both emphasized that the bill should help strengthen the American manufacturing and clean energy industries. In a statement to WIRED, a GM spokesperson wrote that the bill fits into its “work to establish the U.S. as a global leader in electrification.”

But automakers and resource companies alike warn that the changes will not occur overnight. Mining and refining can be a dirty business, and homegrown projects are likely to face local opposition. Even if projects are approved, “there’s a combination of national and local decision making around the sites, because every site is in a state and county,” says John Loehr, a managing director in the automotive and industrial practice at the consulting firm AlixPartners. “There can be many complications.”

So in many cases, auto and battery makers are still likely to source their raw or partially processed battery materials—including graphite—from China. It is unclear whether a vehicle that contains material that touches China, however briefly, will ever qualify for the new tax credit. If it is, a portion of the industry may be in a bind for a few years as it continues to be strapped for materials and demand skyrockets. “You’ll miss every goal that you don’t go after,” Huston says. “If we don’t have these milestones, we’ve guaranteed not to hit them. But if we have them, maybe we get halfway there.”

Ampofo, the metals and mining analyst, says to not count out American technological ingenuity—innovation could, say, totally reorder battery chemistries for the better, or cut out a now-crucial refining step. Tesla has, for example, teased a new and cheaper approach to lithium extraction. Policies like those outlined in the new bill “are the sort of incentives and opportunities that lead to research breakthrough technology,” Ampofo says. “We’re very optimistic that technology can actually influence some of these constraints that we’re talking about today.”