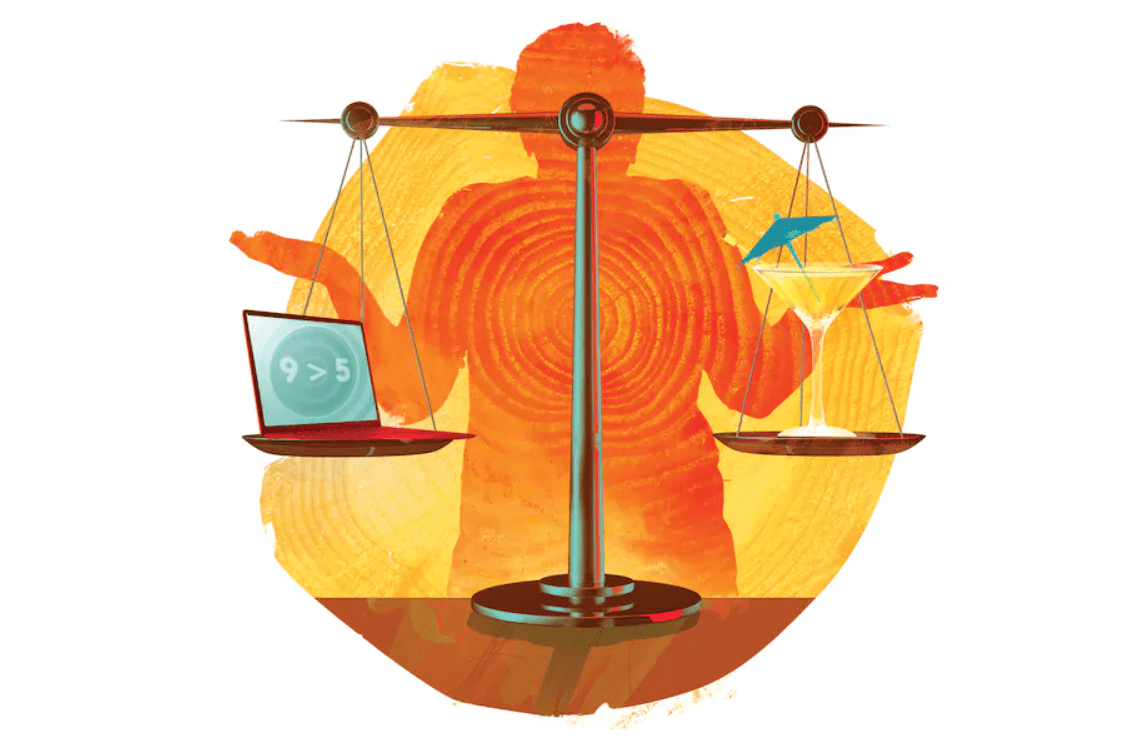

Retire early and live longer? Or to stay healthy, work until you drop? If you search the Internet for advice on how retirement may affect your health, you will probably come across both these statements.

To make things more confusing, catchy anecdotal evidence support these opposing ideas. You may hear about Shigeaki Hinohara, a Japanese longevity researcher, who claimed that working kept him healthy, and toiled 18 hours a day until the day he died at age 105. Or you may read stories of people happily ditching their jobs to suddenly recover strength and travel the world.

Scientific literature appears no less divided at first glance. For instance, various studies conducted in the United States, Austria, Greece and Denmark all found a link between working longer and reduced mortality risk — which roughly means that within the follow-up period of a particular study (say, five years or 10 years), certain people were less likely to die than they would otherwise be expected to. The U.S. study, of nearly 3,000 healthy retirees stepping away from their jobs on average about age 65, found that the longer people worked, the lower their mortality risk.

Yet a different U.S. study of more than 6,000 people 50 and older found “strong evidence that retirement improves reported health, mental health, and life satisfaction.” Studies in the Netherlands and Japan also noted the positive effects of retirement on health.

The message was probably best summed up in a 2020 meta-analysis, the gold standard for research, which looked at 25 studies and concluded that the effects of retirement on health are “mixed” — sometimes positive, sometimes negative depending on a variety of factors

So how should we think about when to retire and what it might mean for health?

Mo Wang, retirement researcher at the University of Florida, says some of the confusion in the studies stems from the fact that often they “do not take into the account the health issues as reasons for retirement.” He says, however, this “healthy worker effect” does not explain all differences in studies between those who stay on their jobs and those who leave. The rest is probably due to retirees being a diverse group — with various types of jobs and life circumstances — so if you lump everyone together, you will get confusing results.

That is key, says Maria Fitzpatrick, a social scientist at Cornell University who studies the health effects of retirement.

“What happens in retirement is going to be different for different people depending on what they did before retirement and what they do after.”

Based on his research, Wang says “about 20 percent of retirees . . . see their health go through some decline” after retirement, while “for about 5 to 10 per cent of population, retirement is really good for their health.” Research also suggests that the health status of those in manual professions won’t be hurt and may benefit from working longer years — provided the job itself doesn’t cause them health troubles.

In general, says Cécile Boot, an occupational health researcher at Amsterdam University and one of the authors of the mixed results meta-analysis, “if you have a healthy job” — meaning one that fits your capabilities well and is satisfying and not too stressful — “working is good for your heath.” That’s hardly surprising since work stress has been linked to a variety of health ills, including diabetes and heart disease.

Another important issue when it comes to retirement and health is whether you decide to step down yourself, or are forced to do so. A study of nearly 800 Dutch workers, for instance, found that those who felt pushed into retirement tended to judge their physical well-being as worse than those who decided on their own to stop working, no matter their initial health.

And then, there is the social aspect of life after retirement.

If your marriage is unhappy, research suggests that your health may decline — or seem worse — after you quit work and are home more. Unmarried men heading into retirement appear to be more at risk, too. Having had a highly social job, such as in customer service, can also affect mental and physical health in retirement. For such people says Wang, “retirement creates a big issue for their day-to-day activities and their social life quality.”

A2018 meta-analysis that looked at 151 studies involving more than 700,000 people concluded that when people retired their social integration tended to suffer. As a result, they may end up participating in fewer group activities and having fewer friends. This can have profound effects on health. Studies have found that building a strong support network can lower mortality risk by about 45 percent. For comparison, exercise can lower that risk by 23 to 33 percent, while following the Mediterranean diet can lower it by 21 percent.

For this reason, many researchers suggest that those thinking of retiring should take time to prepare for it not only financially but also psychologically and socially.

Keeping engaged and joining various social groups seem to be linked to better health and satisfaction after retirement. “Being embedded in high-quality close relationships and feeling socially connected to the people in your life is associated with decreased risk for all-cause mortality as well as a range of disease morbidities,” as a 2017 review put it.

Among the notable pathways to a socially connected, happy and healthy retirement is volunteer work. A meta-analysis of 14 studies found that volunteering was linked to a reduction in mortality risk of 24 percent.

It can also help us find meaning in retirement, which “is a very important thing for the retirement life to be [perceived by someone as] good,” Wang says

When people are younger, it’s their work that often provides them with meaning and purpose. In retirement, Wang suggests, “mentoring students, helping raise the younger generation” can provide those same feelings. According to meta-analysis of observational studies, it may also reduce mortality by 17 percent.

Above all, what emerges from research is that retiring to your couch to binge on TV shows is probably not the best way to spend your time. Yet studies have found that’s what some people do.

Fitzpatrick, in a 2018 study that looked at 33 years of U.S. mortality data, found that male deaths in the United States spiked immediately after age 62, when many Americans begin claiming Social Security.

People who were the most vulnerable to this post-retirement mortality, Fitzpatrick says, seemed to be those who retreated from society and became less active physically and socially. Since many of the deaths in the study were respiratory-related, poor lifestyle choices such as smoking or lack of physical exercise could be responsible, she says.

That’s why Fitzpatrick — like other experts interviewed for this article — advises people to pay special attention to the period right after they leave their jobs and head into retirement.

“Stay physically active, eat healthily, engage in activities that provide you with good social and mental stimulation and engagement with the world around you,” Fitzpatrick says. “Because retirement is such a big transition, and [in] such a time of uncertainty, people who are considering retirement or entering retirement should just be extra careful to do those things.”