Is the global monetary order ready for another reboot?

In the 1960s, Japan and Europe exported their way to post-World War II prosperity under the fixed exchange rates of the Bretton Woods agreement. The U.S. went off the gold standard in 1971, but the established way of doing things didn’t collapse. Thirty years later, China essayed the role of being the world economy’s periphery and selling cheap widgets to a revamped core — the West and Japan — with the help of an undervalued exchange rate.

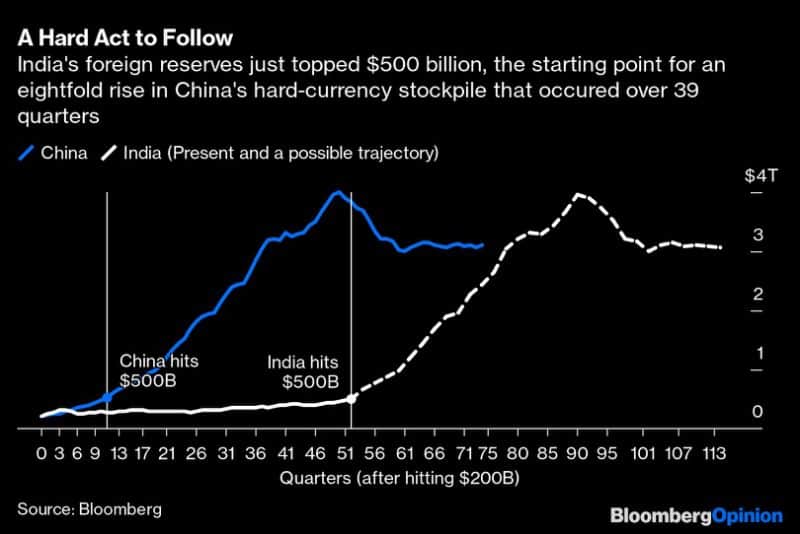

This, as economists Michael P. Dooley, David Folkerts-Landau and Peter M. Garber noted in an influential 2003 essay, was Bretton Woods revived. The “China phase,” they said, would play out over 10 to 20 years as the world economy absorbed 200 million surplus rural Chinese workers at the rate of 10 million to 20 million a year. To that end, Beijing would acquire vast quantities of foreign-exchange reserves regardless of cost. And when China was done, India would take its place. Will it?

One clue may lie in official reserves. By purchasing the public debt of a profligate center, a hardworking fringe signals its reliability; any threat to Western business investments, and the periphery’s holdings of U.S. Treasuries and other safe assets could get cancelled. (Far-fetched as it may sound, the idea did get discussed recently when President Donald Trump’s administration was contemplating punishing China for its handling of the coronavirus outbreak.)

By the time Dooley et al got down to writing, “The Revived Bretton Woods System’s First Decade” in 2014, China’s reserves were peaking, at about $4 trillion, from under $300 billion at the time of their original study. Just recently, India’s foreign-exchange stockpile crossed the $500 billion mark. In 1990, the country only had enough dollars to pay foreign suppliers for half a month. Now the reserves cover two years of imports.

Yet the domestic political discourse is harking back to a protectionist past. Prime Minister Narendra Modi wants self-reliance. Other officials are coaxing Indians to buy local even if means paying more. It doesn’t look like India sees itself as the world’s next factory, which requires openness. Emboldened by its recent free trade agreement with the European Union, Vietnam may be more suited to playing that role, even though the Southeast Asian nation of fewer than 100 million people lacks India’s labor power.

Some of India’s retreat may be tactical and temporary. The U.S. is still coping with China’s rise, and not in a mood to let another 200 million workers latch on to its customers. Industrialization of the periphery requires a fundamental restructuring of the labor force in the core, as the authors of Bretton Woods 2.0 warned. “No country has found a workable way to compensate its own losers.”

The Western companies that chose China as a manufacturing location became vocal supporters of its developmental strategy and shielded it from politicians and labor unions in their home countries. This global businesses elite is no longer as powerful amid a rising anti-globalization tide almost everywhere. The threat of being branded a “currency manipulator” by the U.S. Treasury also limits the extent to which the Reserve Bank of India can intervene in the foreign-exchange market.

Then there’s Covid-19, and the worst global recession since the Great Depression. While a rapidly deteriorating relationship with Beijing impels Washington to draw the only other billion-plus-people country deeper into America’s embrace, massive unemployment in an election year makes it impossible to grant concessions. India understands the compulsions. When President Donald Trump recently ordered a freeze on H1-B visas used by technology workers through the end of this year, there was disappointment in the country’s outsourcing industry, but no sense of doom.

India has its own constraints. After its Himalayan border with China witnessed the deadliest conflict between the nuclear-armed neighbors in 45 years, there’s little prospect for deeper economic engagement between the two. India’s trade with China is $50 billion in deficit, while that with the U.S. is $22 billion in surplus. The talk of self-reliance in New Delhi may simply be code for weaning the economy off Chinese goods and capital. Hundreds of millions of pandemic-hit Indian workers need jobs, even if that means making things like solar panels that China can supply far more competitively.

The Western tech industry, which remains broadly excluded from China, will probably advocate for India. Even here, though, India’s powerful local business lobby will seek to define the rules of engagement. After investing billions of dollars in the country, Amazon.com Inc. still can’t maintain its own e-commerce inventory. Facebook Inc. has waited for two years for approval for its popular messaging service WhatsApp to send and receive payments.

Eventually, investment banks will enable joint ventures and compromises. Indian tycoons’ wealth is tied to stocks traded in Mumbai. However, if they could float their businesses in New York — just as worried Chinese companies leave to seek listings closer to home — they would happily support an artificially low rupee. That would give them an export advantage while enabling them to be counted among the global rich. Bretton Woods could yet reload.