A burning meteor is headed for the wide, weird world of online Flash games. Adobe will discontinue support for Flash at the end of 2020, rendering the delightful—and sometimes disturbing—’90s- and aughts-era browser games unplayable. It’s bigger than losing access to classic time-wasters like Desktop Tower Defense and Line Rider. A seminal digital culture is at risk. To stave off annihilation, a small underground movement of digital preservationists is fighting hard to spare the little Flash games from their fate.

Ben Latimore, a 26-year-old Australian who goes by the handle BlueMaxima online, has saved over 38,000 Flash games in a behemoth torrent as part of Flashpoint, a webgame preservation project. He set out in 2017, along with a band of nostalgic programmers and curators he’d met on vintage-game emulation forums, to create “an all-in-one archival project, museum, and playable collection of Flash games, as safe as possible from the eventual death and server shutdowns of Flash game sites.” Asked why it’s important to archive Flash games this year, Latimore responded, “This year? Try four years ago, when the shutdown was first announced. Hell, try six, when people knew Flash was on a downwards spiral. Hell, try 10, when Steve Jobs announced that Flash wouldn’t be making the jump to Apple mobile devices, practically sealing the coffin shut then and there.”

Right now, the Flashpoint torrent is 241 gigabytes, downloadable to any Windows user for free—all in the name of conservation.

“Flash offered animation and game development tools to people who may otherwise have never had them.”

TOM FULP, NEWGROUNDS

In the early 2000s, bawdy Flash games were cultural currency. Hyper and snacking on Doritos 3-D, kids traded The Worlds Hardest Game for Commander Keen—free games they’d play in-browser for hours and hours—over AOL Instant Messenger. On sites like Newgrounds.com or AddictingGames.com, bored office workers trawled the digital game aisles in search of a small dopamine hit. These weren’t polished masterpieces. In fact, some of them were blatant copycats, like Super Mario 63, or irreverent pulp, like school-shooting game Pico’s School.

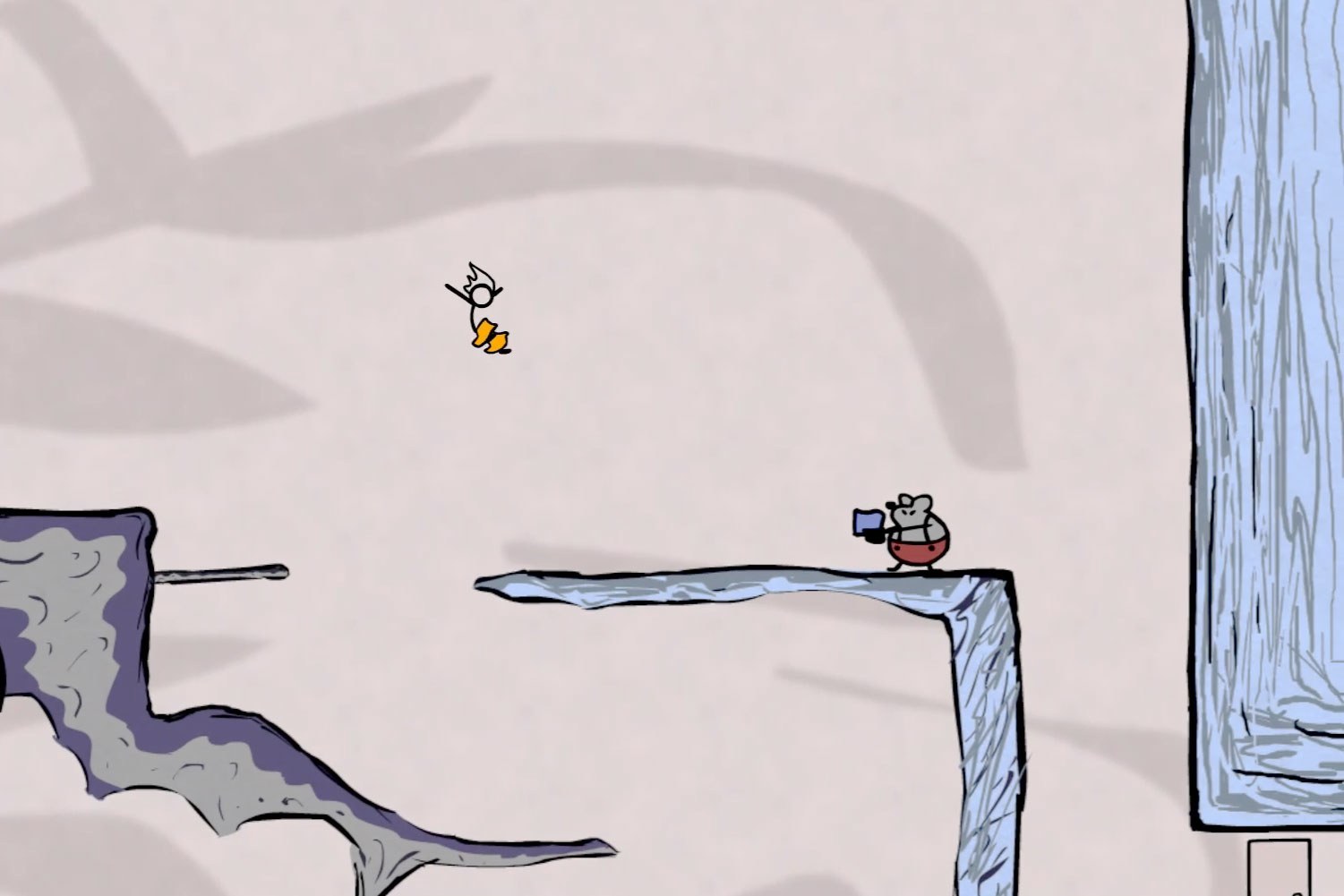

“With Flash games, you threw something out there and people liked it or didn’t like it,” says developer Brad Borne, who created the Flash-based Fancy Pants Adventures in 2006. “It’s a very pure relationship between the developer and the audience. There’s no microtransactions, no ads. It’s just, is the game good?”

Studying psychology in college, Borne stumbled upon a Breakout-type Flash game in the early 2000s. On a whim, he decided to copy it. He’d never considered videogame design as a career or even a long-term hobby, but something about the handmade look of that Breakout Flash game got him thinking that, hell, he could make that too. And because he could put his creation directly online, no big publisher or tastemaker or store curator could quash it.

Back then, if you were really lucky, Newgrounds founder Tom Fulp—who made his own Flash games—would like your game and drop it on the front page of his hugely trafficked site. Addicting Games developed or distributed 10 to 20 games a week, which owner Bill Kara says were played by millions. It was a free, or free-ish, ecosystem for indie developers and digital dilettantes.

“Flash offered animation and game development tools to people who may otherwise have never had them,” says Newgrounds’ Fulp. The videogame designers behind celebrated titles like Crypt of the Necrodancer, Hollow Knight, and Super Meat Boy all got their start noodling around with Flash, Fulp says. Fans of the Angry Birds franchise, which still generates hundreds of millions of dollars yearly, generally acknowledge its huge similarities to Crush the Castle. Bejewled started as a Flash game. The movement created a hunger for small, weird little games with low barriers to entry.

By the time Abode announced in 2017 that it would kill Flash, it was already dying. Developers shifted to HTML5. The biggest browsers—Chrome, Safari, and Microsoft Edge—limited Flash or turned it off by default. Flash was and continues to be rife with security issues and exploits. But while beneficial for internet safety at large, losing Flash came at a cost. The vibrant digital artifacts created using the technology would soon become obsolete.

After the announcement it dawned on Latimore that he didn’t know anyone making any effort to preserve, in his words, “this unmatched historical artifact of 2000s internet society.” A little Googling left him shocked at how difficult it was to find public preservation plans on Flash portals like Armor Games and NotDoppler. Initially, he intended to just back up those portals. As his project attracted attention from like-minded game preservationists, he was approached by what is now a team of 30 developers in Flashpoint’s Discord group of over 7,000 contributors and fans.

To preserve those Flash games, “curators” search for and submit candidates for the archive, while others add museum-style descriptions for the games, test them out, and build out the custom open-source front end. Latimore says that 90 percent of the games consist of only one Shockwave Flash file, without locks or additional assets, making them relatively easy to port.

“The rest is where it gets tricky,” he adds. “Everything from site locks that prevent the games from being played anywhere but on their official website, multiple resources that load after the first SWF [Shockwave Flash file format] that pretty much every web crawler can’t get to, or games that require servers for things like custom levels, or even to be played at all, are the tricky ones.”

To help get around those issues, says project contributor Sonam Ford, Flashpoint didn’t exactly make a Flash emulator—software that lets a computer mimic another system. It’s an internet emulator. Flashpoint uses a local proxy server setup to convince games they’re running on their original sites, “bypassing site locks and other protections that would normally prevent the games from running offline,” Ford says. “We use Adobe’s official Flash projectors, which will run stand-alone even after Adobe discontinues Flash support,” he adds. “It’s important to note that Adobe discontinuing support for Flash doesn’t mean that Flash will stop running on your computer after it’s set up properly.”

To this day, pirates remain at the forefront of the game preservation movement.

Flashpoint isn’t the only organization preserving Flash games. Newgrounds launched Newgrounds Player, a desktop app that plays Flash games that no longer work in-browser. (Adobe gave Newgrounds a license to distribute the Flash player as part of it.) Addicting Games will let users play their 5,000-plus Flash games locally on their computers, and is porting some of their classic Flash games to HTML5. Other game developers are individually porting their own games to mobile, console, and PC. However, Flashpoint works entirely offline, which keeps the games safe from the shifting tides of internet software.

(Flashpoint’s removal from the internet should also help insulate it from the security flaws that have plagued Flash’s online existence, and that will only get worse after Adobe pulls support. “In a controlled offline environment there’s not much that can be done to exploit them,” says Flashpoint contributor Alejandro Romanella.)

On top of technical demands, game preservationists face an uphill battle against copyright law. Imagine if you made a painting, but the brushes, paint, paper, and image were all licensed. This is the challenge: playing old games requires owning or modifying proprietary hardware and software.

“The early history of game archiving is 100 percent pirates,” says Alex Handy, director of the Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment. “The Atari ST—a computer system from the mid ’80s—the only reason we have all the software for that system is because pirates cracked it, compressed it, and put it on floppy discs.” Handy hopes that Flash games can avoid the fate of silent films, 75 percent of which are lost forever.

To this day, pirates remain at the forefront of the game-preservation movement. When a game is made for an older platform but can’t be played on any newer ones, pirates craft ROMs—computer files containing copies of data from videogame cartridges—which gamers play on emulators. While emulators are legal, ROMs are considered to fall under the category of “copyright infringement.”

Nintendo has famously gone after websites like LoveRETRO, LoveROMS, and RomUniverse, seeking damages in the millions. In 2018, huge retro-gaming site EmuParadise removed its library of ROMs after two decades of legal threats.

Latimore is running up against this tension on a smaller scale with Flashpoint. While several developers have reached out to Flashpoint devs to thank them for their preservation efforts, others aren’t as happy. A couple have reached out expressing discomfort about their games’ free distribution. One independent game developer aired a complaint more recently, forcefully asking Latimore to remove their games.

“Just because what you are trying to do has a noble aim, that does not give you the right to take and redistribute other people’s content without their consent,” says Matthew Annal, CEO of game studio Nitrome. Nitrome is exploring its own vehicles for preserving and distributing their games. But the company would like to continue making money, Annal says, for as long as Flash continues to work.

“It’s not hard to understand their position,” says Latimore of Nitrome. “Meanwhile, you have us; we want to save these previously freely available games in their original forms. It’s a tough question.”

Either way, he adds, he’s going to keep a couple of copies of Nitrome games in his back pocket. “For safekeeping,” he says, “even if we don’t publicly distribute them.”