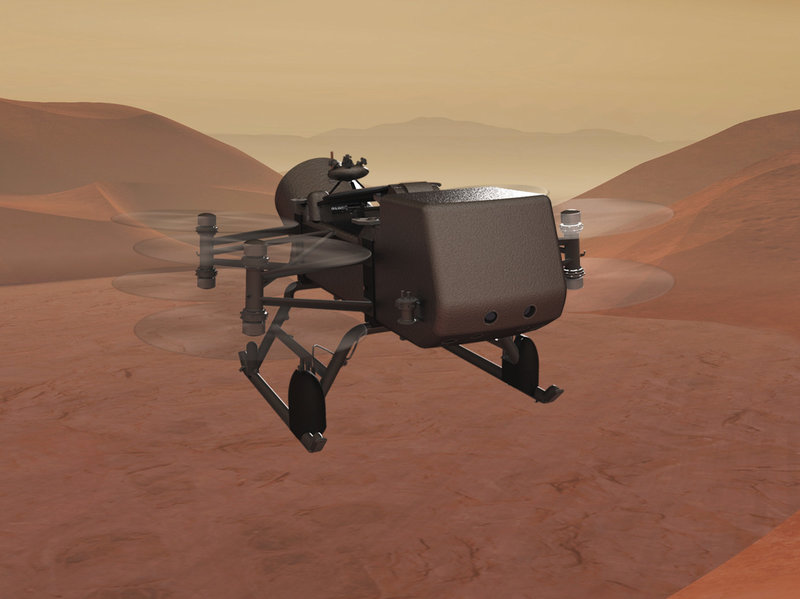

On the face of it, NASA’s newest probe sounds incredible. Known as Dragonfly, it is a dual-rotor quadcopter (technically an octocopter, even more technically an X8 octocopter); it’s roughly the size of a compact car; it’s completely autonomous; it’s nuclear powered; and it will hover above the surface of Saturn’s moon Titan.

But Elizabeth Turtle, the mission’s principle investigator at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, insists that this is actually a pretty tame space probe, as these things go.

“There’s not a lot of new technology,” she says.

Quadcopters (even X8 octocopters) are for sale on Amazon these days. Self-driving technology is coming along quickly. Nuclear power is harder to come by, but the team plans to use the same kind of system that runs NASA’s Curiosity rover on Mars. Everything that’s going into Dragonfly is already being used somewhere else.

Which is not to say that the idea of a nuclear-powered drone flying around a moon of Saturn doesn’t sound kind of crazy.

“Almost everyone who gets exposed to Dragonfly has a similar thought process. The first time you see it, you think: ‘You gotta be kidding, that’s crazy,’ ” says Doug Adams, the mission’s spacecraft systems engineer. But, he says, “eventually, you come to realize that this is a highly executable mission.”

NASA reached that conclusion when, after a lot of careful study, it gave Dragonfly the green light earlier this summer. “This revolutionary mission would have been unthinkable just a few short years ago,” NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said when the roughly $1 billion project was selected in June. “A great nation does great things.”

For Shannon MacKenzie, a postdoc on the mission, there’s no destination that could be greater than Titan. The largest moon of Saturn, it has dunes, mountains, gullies and even rivers and lakes — though on Titan, it’s so cold the lakes are filled with liquid methane, not water.

“It is this complete package,” she says. “It’s this really unique place in the solar system where all of these different processes are coming together in a very Earthlike way.”

Turtle says these features are part of what made Titan a target. It also appears that the surface is covered in organic molecules. The climate is probably too harsh for those molecules to make the shift into life, but Turtle thinks Titan could provide clues about how the building blocks of life started on Earth.

“All of these materials have been basically doing chemistry experiments for us,” she says. “What we want to be able to do is go pick up the results of those experiments to understand the same kinds of steps that were taken here on Earth toward life.”

Titan has one more feature that’s worth noting: Although its mainly nitrogen atmosphere is denser than Earth’s, its gravity is far lower. That makes it the perfect place to take to the skies.

“The conditions on Titan make it easier to fly there than on Earth,” says Peter Bedini, the Dragonfly project manager. A drone is actually a much better way to explore such a world than a wheeled rover.

Dragonfly will launch from Earth in 2026 and arrive on Titan in 2034. After it enters the atmosphere, it will literally drop from the back of the capsule that brought it and fly down to a set of sandy dunes on the surface. From there, it will make a series of “hops” over two years, sampling the ground and sending back data and photos.

Adams is confident Dragonfly will be able to safely buzz across Titan’s terrain. Because it can take nearly an hour-and-a-half for a signal to reach Titan from Earth, it will have to fly autonomously. But, he says, there’s not a lot to run into: “We make the joke if we hit a tree, then we win because we found a tree on Titan,” he says.

Adams plans to leverage a lot of technology from the recent drone revolution here on Earth. Radars, motors and software can all be used, or relatively easily adapted, for Dragonfly.

There is one thing he can’t bring, however: “We don’t actually have a map. There’s no GPS; there’s no magnetic field even to orient yourself,” he says. He says the drone will navigate by continuously photographing the landscape, creating its own “map” as it goes.

For now, the Dragonfly team is still working with drones here on Earth to figure out how to build systems and software the probe will eventually need. But Turtle says they have time before the 2026 launch. “There’s a lot to do between now and then,” says Turtle. But she adds, it’s all very doable.