Jessie Kelly knew there was an excellent chance she would end up on strike at General Motors. Long before her union, the United Auto Workers, declared a work stoppage this weekend, the 29-year-old mother of one began socking away savings to prepare for a long battle with the Detroit automaker.

“I could live out three months,” Kelly, an apprentice moldmaker at the GM Technical Center in Warren, Michigan, told HuffPost. “I 100% feel this strike is necessary.”

No one knows how long the largest auto strike in more than a decade will last. But workers like Kelly have dug in and don’t plan to bend. They look at how well GM has done in recent years ― the company pulled in roughly $11 billion in pre-tax profits in 2018, and about $35 billion over the last three years combined ― and wonder why they shouldn’t have a larger piece of the pie.

“They shuffle us into a room every six months and praise these record-breaking profits, but they expect us to give back,” Kelly said. “We just do not understand right now why the company is still acting like we’re in bankruptcy when for the last four years they’ve been extremely profitable.”

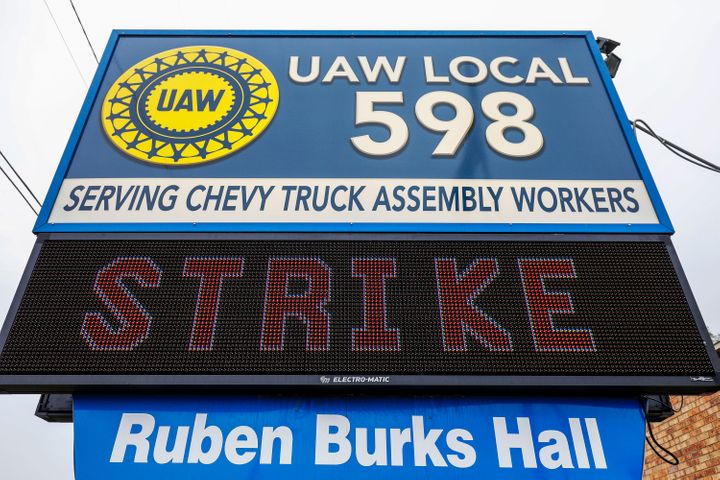

Her outlook goes a long way in explaining why nearly 50,000 UAW members have stopped production at more than 50 GM facilities nationwide. The union said Sunday that the two sides remain far apart in negotiations, with a raft of outstanding issues to resolve. But the root of the deadlock is not hard to grasp.

GM very much wants to keep its costs down as auto sales slow and the company makes bets on electric vehicles. But GM workers told HuffPost they still recall the sacrifices the union made as the industry foundered in 2007, before the company returned to profitability. The concessions they made back then, including a two-tier wage system, still cast a shadow over the current talks.

Though workers have shared in GM’s strong performance since then, with profit-sharing bonuses that can top $10,000, they see no reason to bend to the company given its recent track record.

To be clear, few people away from the bargaining table know the biggest hurdles to a deal. Union leadership has not shared the company’s proposal with members. GM disclosed a few pieces of its offer, including promises to allocate production to two facilities that had been idled, an overall investment of $7 billion in UAW-represented plants, and worker bonuses of $8,000 for ratifying the contract ― what the company deemed a “strong offer” made in good faith.

But pay hikes and other benefits were not specified. The union and GM could easily be at a deadlock over wage increases, health care costs and other, even trickier issues that were expected to be central to the talks.

Workers said they believe GM and the union need to bridge class divisions within plants. It takes newer workers eight years to reach the top pay rate of roughly $30 per hour earned by longer-term veterans. That’s better than in the wake of the financial crisis, when new hires had no way of reaching that rate at all ― a compromise the union made as the company veered toward bankruptcy.

But many workers believe the “in-progression” system, as it’s known, is still too long a slog. After all, it takes the duration of two collective bargaining agreements to complete it.

They also want to limit GM’s use of temporary workers. The company says about 7% of its U.S. workforce is temps, though the share can vary significantly from department to department and shift to shift. Some workers temp for two years or more before transitioning to full-time and gaining job security. GM may be pointing to foreign-owned transplants like Nissan, where temporary workers are more widespread, and asking for similar leeway.

In a letter to members Sunday, UAW Vice President Terry Dittes said the outstanding issues include the in-progression wage system as well as “the treatment of temporary workers.”

Beth Baryo, a parts handler at GM’s processing center in Burton, Michigan, said guaranteeing that more temps convert to traditional status was a priority for her and her co-workers. Baryo started with GM in 2014. She temped for 18 months before becoming a full-time employee, and she hasn’t yet reached the top pay rate.

She was out on the picket line at her plant at midnight Monday morning and found it was difficult to convince some temps to join the strike because they felt vulnerable. She estimated that nearly half the department on her evening shift is temporary, in part because the shift is less desirable.

“They have temps who come in and are next to people making twice what they make… A lot of them were scared to even walk out,” Baryo said. “We had to explain to them, ‘No, if you walk out with us, [the union is] going to fight for you.’”

She added, “I would be scared, too.”

Crain’s Detroit Business reported Monday that GM wants workers to bear a significantly larger share of the health care burden. The workers generally have excellent health coverage and are responsible for around 3% or 4% of the cost. According to Crain’s, GM’s initial offer would have hiked that share to 15%, a proposal the union rejected.

“They’re trying to start eroding a lot of the progress our forefathers made through the union,” said Baryo.

Whatever contract the union reaches with GM would serve as a template for its talks with Ford and Fiat Chrysler, the remaining two-thirds of the Big Three. But even if the UAW leadership can squeeze a deal out of GM that they like, it doesn’t mean it will go over with workers like Baryo.

When the union was negotiating its last contracts with the Big Three four years ago, workers at Fiat Chrysler voted down the initial tentative agreement the union had secured. Their rejection eventually led to a better deal allowing for in-progression workers to reach top pay. If rank-and-file GM workers don’t like the offer put before them, they can take a page from the 2015 playbook and vote it down, sending everyone back to the table.

The last strike at GM lasted just two days in 2007 and inflicted minimal pain on the company and workers. A strike that lasts weeks would be far more damaging. Analysts say the plant closures could cost GM at least $50 million a day in revenue. It wouldn’t be long before the strike would be visible on dealer lots.

And even though the strike is taking place only in the U.S., it could also hurt production in Mexico and Canada due to the company’s integrated production across North America.

As for workers, the UAW has grown a healthy strike fund of more than $700 million, thanks in part to a temporary dues increase to prepare for this year’s contract fight. But workers would still collect only $250 a week in strike pay, hardly enough to carry a single worker, let alone a family.

Kelly brought her 6-year-old son out on the picket line Sunday and to her union hall on Monday. Even though a long work stoppage would be financially trying, she said she felt reassured when she saw the sense of unity among her co-workers.

“We as a membership have prepared to say this could be a long strike,” she said. “We stood by GM in bankruptcy. We took concessions and we understood why we needed to at that time. If this was 2007, that would be understandable. But not now, when it just looks like corporate greed.”