An increasing number of countries are exploring the potential to develop their geothermal energy capacity as governments look to expand their energy portfolios to include a broader range of renewable sources. As the U.K. assesses its deep geothermal potential, a major Japanese utility is betting big on geothermal energy in Germany, and Kenya is taking a regional approach to developing capacity. Greater investment in the sector is expected to continue supporting technological breakthroughs to draw investor interest and make operations more economically viable.

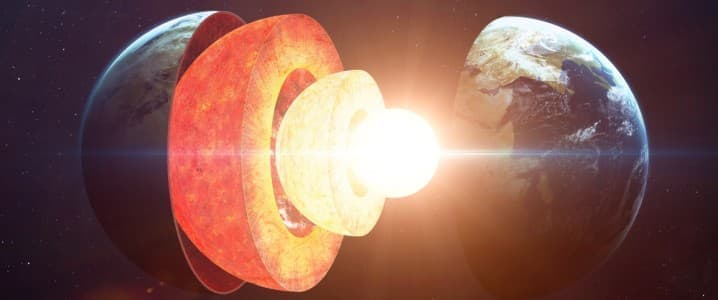

Geothermal operations use steam to produce energy. This steam is derived from reservoirs of hot water, typically a few miles below the earth’s surface. The steam is used to turn a turbine, which powers a generator to produce electricity. There are three varieties of geothermal power plants: dry steam, flash steam, and binary cycle. Dry steam power plants use underground steam resources, piping steam from underground wells to a power plant. Flash steam is the most common form, using geothermal reservoirs of water with temperatures above 182°C. The hot water travels through wells in the ground under its own pressure, which lessens the higher it travels to produce steam to power a turbine. Finally, binary steam power plants use the heat from hot water to boil a working fluid, typically an organic compound with a low boiling point, which is then vaporised in a heat exchanger and used to turn a turbine.

British Geological Survey (BGS) and Arup, a British engineering consultancy, recently developed a White Paper entitled ‘The case for deep geothermal energy — unlocking investment at scale in the UK’, funded by the U.K. government. It aimed to assess the opportunities for constructing deep geothermal projects across the country to help diversify Britain’s renewable energy mix. To develop deep geothermal systems, companies must drill deep wells to reach higher-temperature heat sources at depths of more than 500 m. There is significant potential to develop these resources in the U.K., but the complex drilling operations come at a high cost, which has so far deterred developers.

However, as technologies are improving, thanks to greater funding for research and development in the renewable energy industry, the number of areas where geothermal exploitation is economically viable is expected to increase. Most of the U.K.’s deep geothermal resources can be found in deep sedimentary basinsacross the country. The White Paper recommends that the government promotes geothermal energy as one of the U.K.’s renewable energy resources to boost investor confidence and promote awareness of the energy source. The establishment of a regulatory body could also support the development of new projects, while a licensing system could help streamline future projects.

In Japan, one of the country’s biggest utility groups, Chubu Electric Power, announced plans to buy into a geothermal energy project in Germany. Chabu is purchasing a 40 percent stake in the company, which plans to develop first-of-its-kind geothermal power and district heating project in Bavaria. It will use Eavor-Loop technology developed by Canadian start-up Eavor, transforming sub-surface heat from the Earth’s core into renewable energy, without the need to discover underground hot-water reservoirs. Chabu already invested in Eavor itself in 2022 and hopes to promote the commercialisation of the new technology in Germany.

Meanwhile, in 2022, Kenya – which drilled its first geothermal well in the 1950s and opened its first power plant in 1981, came seventh in the world for geothermal energy production. Kenya produces around 47 percent of its energy from geothermal resources. It is one of only two African countries, alongside Ethiopia, that produces geothermal energy. The East African country hopes to assist neighbouring states with their geothermal ambitions, in a bid to support the regional development of clean energy resources in line with the global green transition. KenGen, the government entity that operates Kenya’s geothermal power plant, is providing technical support to other countries in the region, having already drilled multiple geothermal wells in Ethiopia and Djibouti to assess their potential.

And this month, the governments of Indonesia and New Zealand confirmed their cooperation in geothermal energy projects. Indonesia-Aotearoa New Zealand Geothermal Energy Program (PINZ) has been extended for 2023-2028, with a funding commitment of $9.9 million from the New Zealand government to develop Indonesia’s geothermal industry. This partnership has existed for over a decade, to support Indonesia’s clean energy transition.

Several governments around the globe are increasing their investments in research and development into geothermal energy, aiming to diversify the renewable energy mix and reduce reliance on any single energy source. Investment into geothermal energy technology in recent years has already led to advancements that are expected to make new operations more economically viable, with further breakthroughs expected to come as the global geothermal market is established.