The U.S. electric grid faces simultaneous, evolving pressures. Demand for power from the grid is increasing as people adopt electric cars and building energy is transitioned from gas to electricity. At the same time, climate change is driving more extreme weather. Events like the 2020 heat wave that led to rolling blackouts in California are relatively infrequent, but they are happening more often—and utilities need to be ready for them.

New research points to a flexible, cost-effective option for backup power when trouble strikes: batteries aboard trains. A study from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) finds that rail-based mobile energy storage is a feasible way to ensure reliability during exceptional events.

Previous research has shown that, in theory, rail-based energy storage could play a role in meeting the country’s daily electricity needs. Berkeley Lab researchers wanted to take this idea further to see whether rail-borne batteries could cost-effectively provide backup power for extreme events—and whether the scenario was feasible on the existing U.S. rail network.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty around when extreme supply shortfalls are going to happen, where they will happen, and how extreme they may be,” said Jill Moraski, a graduate student at the University of California Berkeley, a researcher at Berkeley Lab, and the paper’s lead author. “We found that the U.S. rail network has the capacity to bring energy where it’s needed when these events happen, and that it can cost less than building new infrastructure.”

The paper, “Leveraging rail-based mobile energy storage to increase grid reliability in the face of climate uncertainty,” was published recently in the journal Nature Energy.

A ready resource in freight rail

The idea for the study came to Amol Phadke, a Berkeley Lab staff scientist and co-author of the study, while he was watching a long freight train trundle past at a railway crossing. He began counting the cars and tallied over 100 on that single train.

“A thought then struck me—how many batteries could such a massive train carry? If those were used for emergency backup power, how significant would their contribution be?” Phadke writes in a briefing on the study. “A quick, back-of-the-envelope calculation revealed an astounding capacity, potentially sufficient to provide power to every household in Berkeley for a few days.”

To meet electricity demand and build capacity for backup power, the U.S. is building long-distance transmission lines and installing stationary banks of batteries.

“While both of these resources are necessary, we wanted to explore additional, complementary technologies,” said Natalie Popovich, a Berkeley Lab research scientist and co-author of the study. “We have trains that can carry a gigawatt-hour of battery storage, but no one has thought in a cohesive way about how we can couple this resource with the electric grid.”

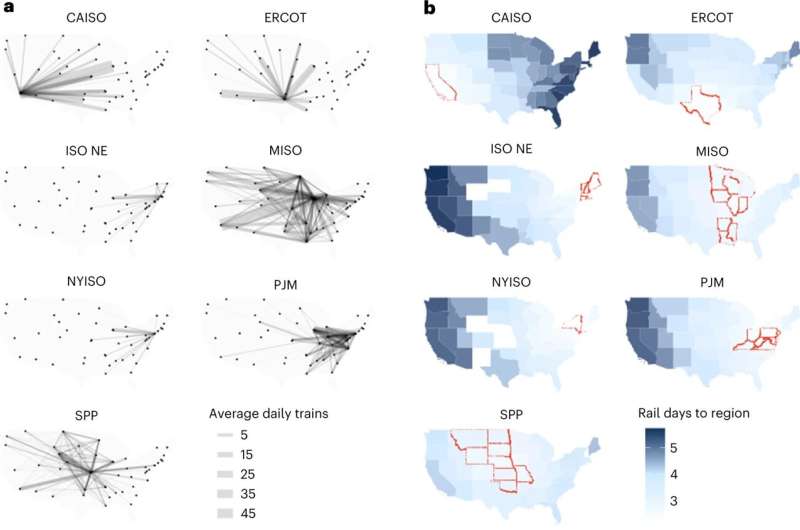

The U.S. rail network is the largest in the world, covering nearly 140,000 miles (220,000 kilometers). The study looked at historical freight rail flows, costs, and scheduling constraints to see whether railroads could be summoned to transport batteries for high-impact events, given that grid operators typically have at least a few days’ notice, and sometimes up to a week, when extreme weather is coming.

The analysis found that mobile energy storage could travel between major power markets along existing rail lines within a week without disrupting freight schedules.

What about stationary options?

The researchers compared the cost of deploying batteries on rail for low-frequency events with the investment costs of stationary energy storage and transmission lines. In cases where the trains need to cover distances of about 250 miles (400 kilometers) or shorter—roughly equivalent to a trip from L.A. to Las Vegas—rail-based energy storage could make more sense cost-wise than building stationary battery banks to fill supply gaps that happen during less than 1% of the year’s total hours.

At those shorter distances, transmission lines remain cost-effective compared to batteries on rail if they are used frequently. When the travel distance grows to more than 930 miles (1,500 kilometers)—say, a trip from Phoenix to Austin—rail becomes cheaper than transmission lines for low-frequency events. This third option could save the power sector upwards of 60% of the total cost of a new transmission line or 30% of the total cost of stationary battery storage, the study concludes.

The study points to New York State, with its robust freight capacity and current transmission constraints between upstate clean energy generation and downstate load centers, as an example of where rail-based mobile energy storage could work well. In other cases, it may make sense for multiple states to share the additional capacity from a rail-based battery bank.

“This is not necessarily a resource that needs to be in one region,” Moraski said. “It can operate similar to an insurance policy, where you spread the coverage across risks for a wide geographic region.”

A train of thought worth following

Regulatory and infrastructure hurdles exist, the authors note. The U.S. lacks adequate interconnections to take power off the train and essentially plug it into the grid. And current electricity markets have no framework for approving, pricing, and regulating a mobile energy asset the way they do for conventional power plants. Policies would need to be revised, and efforts to deploy the storage would need to capitalize on existing interconnections where possible, such as retiring coal plants, which have existing rail lines and interconnection rights.

The researchers see further opportunities to quantify the benefits of rail-based mobile energy storage beyond the scope of the current study, taking into account larger territories, a decarbonized grid, and future climate conditions. They emphasize that extending energy storage across the rail network is not a replacement for important infrastructure such as transmission lines, but could be an important complement.

“Our paper gives a top-level overview of how rail-based mobile energy storage could benefit today’s grid, in today’s climate,” Moraski said. “As we look toward a future with more electrification, more fluctuating renewable energy, and more frequent extreme events, the case for adding rail-based energy storage to the mix may become even stronger.”