More than 250 miles above Earth, a suitcase-size device aboard the International Space Station will soon be used to chill atoms to just a hair above absolute zero, creating the coldest spot in the universe and possibly shedding new light on some of the biggest mysteries in physics.

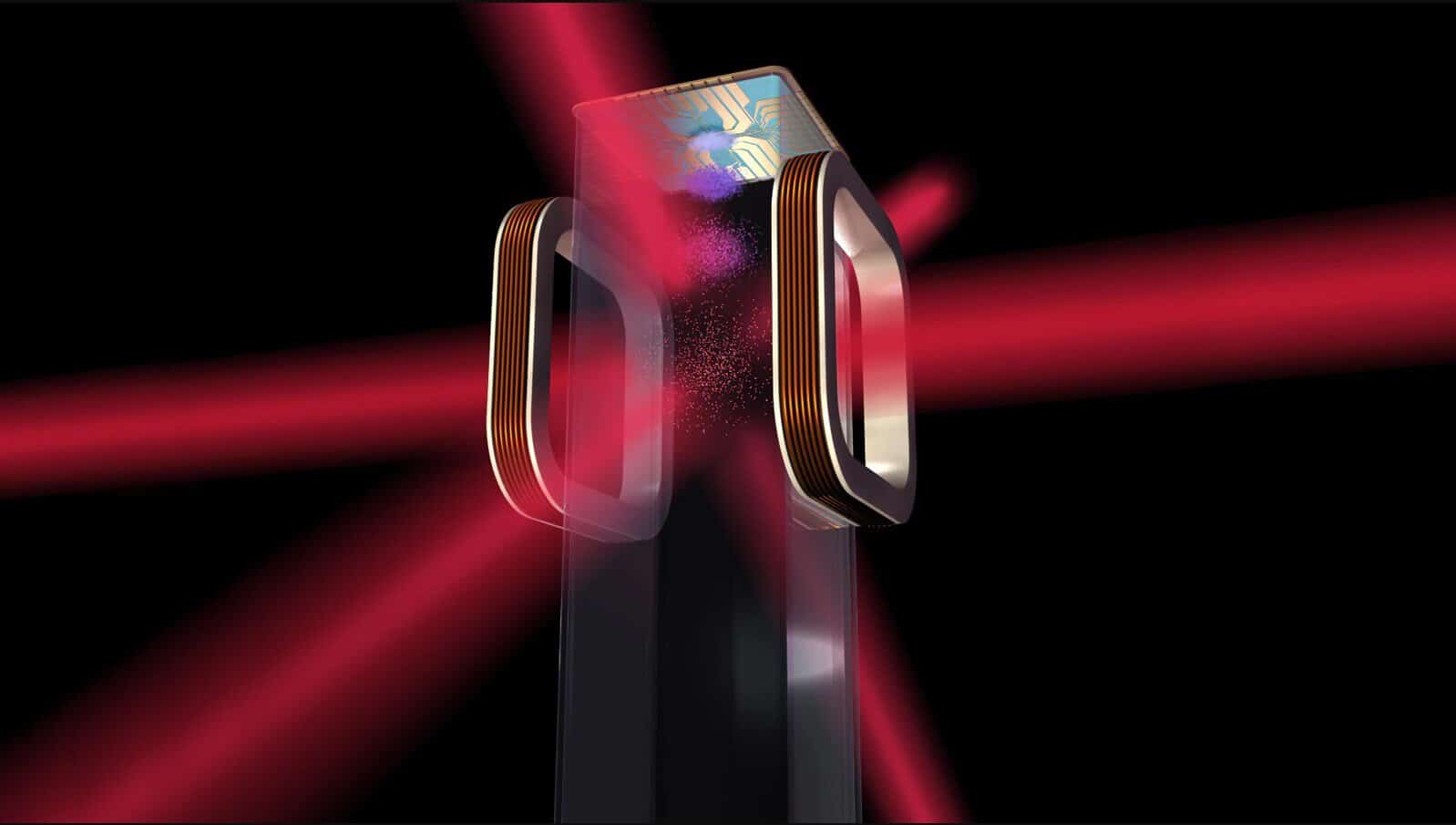

The Cold Atom Laboratory (CAL) device is designed to help scientists study the strange behavior of atoms at ultra-low temperatures — in this case, 10 billion times colder than the frigid vacuum of space.

At these temperatures, atoms clump together to form what scientists call a Bose-Einstein condensate. This exotic form of matter — neither solid nor liquid nor gas — allows scientists to observe the weird world of quantum mechanics, a somewhat mind-bending branch of physics that describes how matter behaves on the smallest scales.

Strange things can happen in the quantum world — for example, a single particle can exist in two places at once — and scientists are hopeful that CAL will help them understand why. “As you cool atoms colder and colder, they become more quantum,” said Robert Thompson, a CAL project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

Bose-Einstein condensates have been created in labs on Earth, but the inexorable pull of gravity makes it hard to study them for more than fractions of a millisecond. In the space station’s microgravity environment, Thompson said, the condensates float to give scientists up to 10 seconds to study them.

In addition to helping scientists gain a better understanding of quantum weirdness, the CAL experiments could point to new laws of physics.

“As far as we can tell, quantum mechanics underlies all of physics, but it violates human intuition and common sense in many ways,” Todd Brun, a professor of electrical engineering at the University of Southern California who isn’t involved with CAL, told NBC News MACH in an email. “There is still no universal agreement about what the theory means, even though we use it all the time to describe real technologies, and know that it works.”

But the high-flying experiment could also have some more tangible benefits.

Thompson said the lessons learned from CAL could speed the development of quantum computers, machines that promise unparalleled processing speed and the ability to tackle problems that are impossible to solve with even the most sophisticated conventional computers.

CAL could also help researchers develop more precise scientific instruments. “Cold atoms are used in atomic clocks, which allow us to measure time with incredible accuracy,” Brun said. “Atomic clocks are used in GPS to measure positions on Earth by timing how long it takes signals to travel.”

But we can’t really be sure what CAL will bring. “Sometimes the benefits to society of research are not directly obvious, especially when you are not sure of how the results will come out,” Barry Garraway, a professor of quantum physics at the University of Sussex in the England who is not involved with CAL, said in an email.

CAL was launched to the space station in May and is now undergoing preliminary tests of its various instruments. Thompson said he and his colleagues expect to begin science operations in late September.