China’s willingness to boycott imported goods in order to inflict economic pain on its adversaries is often referred to as “boycott diplomacy.”

It is a strategy that China has deployed on a number of countries.

At the height of the South China Sea conflict in 2016, China administered an unofficial boycott of mangoes and bananas from the Philippines. The region is still in dispute.

Years before that, China boycotted salmon from Norway during a hotly contested human rights issue, and Norway eventually relented.

Five years back, the world’s second largest economy also boycotted Japanese cars and minerals over a territorial dispute in the East China Sea.

Perhaps most concerning was last year, when China launched an unofficial, wide-ranging boycott of South Korea goods — from entertainment and cars to makeup — in response to the deployment of the THAAD anti-missile system. The boycott hit hard. South Korean carmakers Kia and Hyundai reported a decline in sales, and official figures from South Korea showed a decline in tourism attributed to fewer Chinese visitors.

The fear is that the next country to experience China’s boycott diplomacy will be the US.

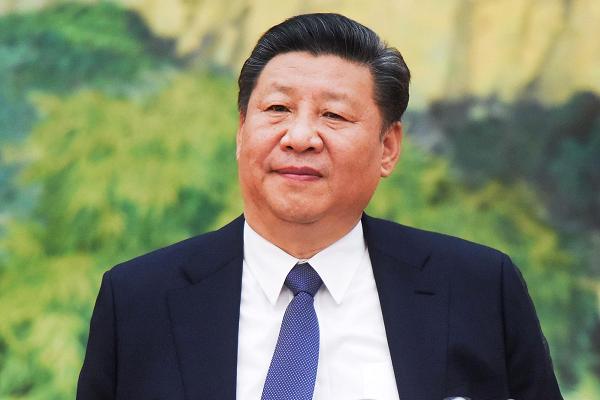

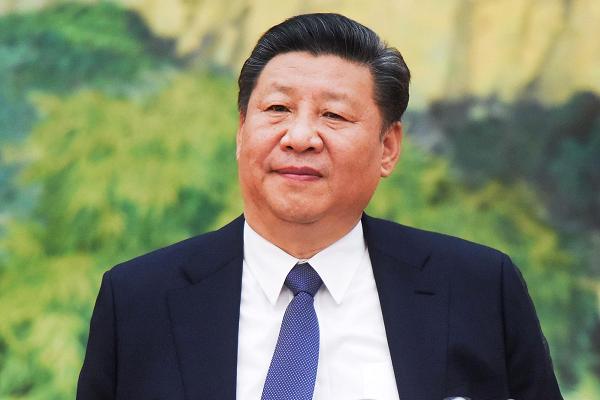

“If President Trump makes good on his threatened 10 percent tariff on $200 billion in Chinese goods, a boycott would be one likely element in a Chinese response,” Elizabeth Economy, the director for Asia studies at the Council on Foreign Relations and author of “The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State,” told CNBC.

Economy went on to say that, “given the high profile and popularity of many American brands and corporations — Starbucks, Walmart, Apple, Nike, and KFC, among them — it will be easy pickings for the Chinese leadership should it decide that it wants to whip up nationalist fervor in support of a boycott.”

Such a move could have severe economic consequences.

“Boycotts politicize trade and thus make consumers and corporations worse off,” Thomas Byrne, the president of The Korea Society, told CNBC. “China scores political points, and does not reap economic gains by the use of boycotts. They are in effect de-factor quotas, and in that sense are worse than tariffs. Smaller countries that have faced boycotts of some of their goods and services sold in China, namely South Korea, are often highly dependent on China’s market.”

But it could push U.S. businesses to look for opportunity beyond China.

“China’s refusal to sell Japan rare earth minerals some years ago apparently led to greater exploration and development outside China,” said Byrne.

China could administer a boycott in non-obvious ways, says Economy, perhaps by rejecting applications from U.S. companies that have requested to expand in China or, out of the blue, ordering inspections at U.S. factories in China, a move that could slow down operations.

Whatever happens next, investors will surely be keeping a close eye on social media platforms like Weibo, which have been used in the past as a communication tool by the Chinese Communist Party to launch boycott campaigns.

“The likelihood of an outright trade war with China remains heightened,” Jack Ablin, chief investment officer of Cresset Wealth Advisors, told CNBC.