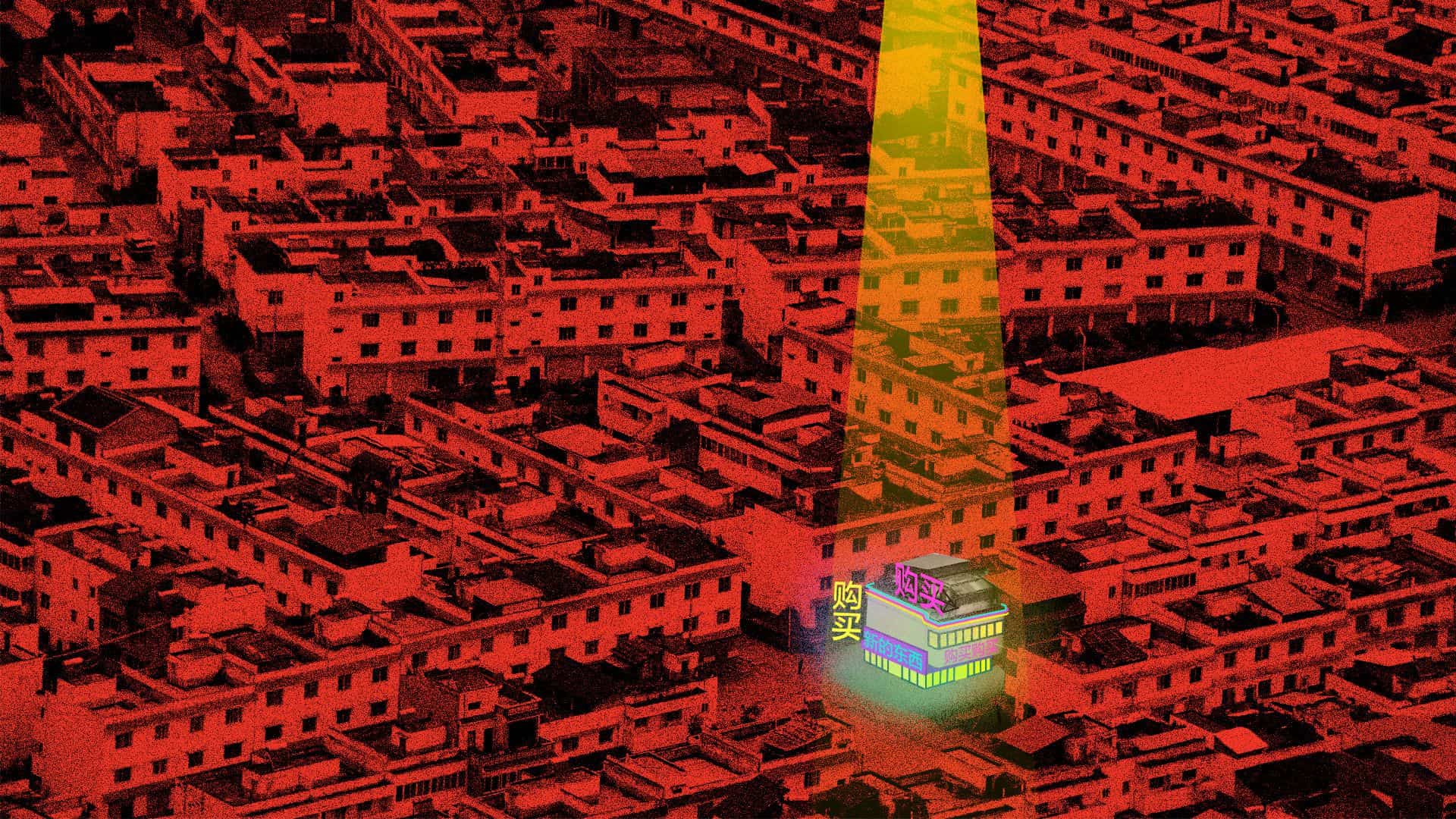

China’s take-no-prisoners Big Tech war is playing out in An Huang’s little family grocery in Hangzhou, a three-hour drive southwest of Shanghai.

What’s going on: A year ago, Huang and his father had a visit from representatives of Alibaba, China’s e-commerce giant. What did they think of transforming their dowdy place into a state-of-the-art, digitalized store, with all the bells and whistles, under Alibaba’s Tmall brand? According to Huang, it took him and his father only about five minutes to agree.

- Today, as he stocks up on popular beer and snacks for the World Cup rush, he told Axios that revenue is up 30% in his spruced-up shop, equipped with artificial intelligence-backed apps and even a heat sensor to track foot traffic.

Why it matters: Alibaba says that over the last year, it has redone about 1 million mom and pop shops like the Huangs’ across China. It has done the same with about a hundred superstores. Big and small, these outlets buy all their goods through Alibaba’s platform and pay using its affiliate Alipay app.

A picture of the future: These stores are examples of an expanding battleground among China’s cutthroat tech giants, and petri-dishes of the future of business around the world.

- Self-contained universes: What Alibaba and rivals like Tencent and JD.com are doing is corralling businesses into branded, self-contained, AI-infused universes in which only their affiliates capture the profit.

- Moving across sectors: Acting rapidly at large scale, they are conceiving and trying out new business models not only in retail, but also investment, lending, payments, and logistics.

Among the central ideas is that in the future, shoppers will not view e-commerce and brick-and-mortar as distinct things, but as a single merged organism — as simply “commerce.” Alibaba regards this concept as so fundamental that only businesses that grasp it will survive.

- By comparison, the West’s tech, retail and financial elite appear lumbering. Even Amazon and Walmart are well behind.

- Many of these slow-moving Western companies risk being overrun by global business and economic trends already in motion.

The details: The cost was relatively low to join.

- Huang paid $6,000 to $7,500 for the renovation, and about $620 a year to be a “super-member” of the program.

- In addition, he committed to buy at least $1,500 of goods per month from the Tmall platform. Dressed in a red Tmall apron, he said these costs are “very low.” “Most people will accept these,” he said. “They are not asking for a share of the revenue.”

The bottom line: These examples of “digitalization in a box” are accelerating China’s evolution in the applied AI future. In effect, it is offering the operating system for going digital.

Alibaba’s competitors — Tencent, JD.com and others — are making similar moves.

- JD calls its effort “retail as a service.” Chen Zhang, JD’s chief technology officer, told visiting journalists last week, “We don’t want to be just a retailer but to help all others run their business better.”

- As of now, there appears to be no similar initiative in the U.S. or Europe. Amazon and Walmart, the most advanced big western retailers, aren’t telling others how to get there, too.

By the numbers:

- China’s e-commerce appetite is huge: Around 42% of global e-commerce transactions took place in China last year, “larger than in France, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States combined,” according to McKinsey Global Institute.

- They are using their phones: China had 772 million Internet users last year, and they spent $812 billion on merchandise using mobile pay apps, 11 times that of the U.S., McKinsey said.

- Alibaba, Tencent and JD dominate. But this is not a friendly exercise: Alibaba and Tencent increasingly force loyalty on firms, requiring them to do business only with them and not their competitors. That practice extends to big foreign brands that wish to sell on Alibaba’s platforms, the Associated Press reported earlier this year.