Renewable energy sources like wind and solar are critical to sustaining our planet, but they come with a big challenge: They don’t always generate power when it’s needed. To make the most of them, we need efficient and affordable ways to store the energy they produce, so we have power even when the wind isn’t blowing or the sun isn’t shining.

Columbia Engineering materials scientists have been focused on developing new kinds of batteries to transform how we store renewable energy. In a new study published in Nature Communications, the team used K-Na/S batteries that combine inexpensive, readily-found elements—potassium (K) and sodium (Na), together with sulfur (S)—to create a low-cost, high-energy solution for long-duration energy storage.

“It’s important that we be able to extend the length of time these batteries can operate, and that we can manufacture them easily and cheaply,” said the team’s leader Yuan Yang, associate professor of materials science and engineering in the Department of Applied Physics and Mathematics at Columbia Engineering. “Making renewable energy more reliable will help stabilize our energy grids, reduce our dependence on fossil fuels, and support a more sustainable energy future for all of us.”

New electrolyte helps K-Na/S batteries store and release energy more efficiently

There are two major challenges with K-Na/S batteries: They have a low capacity because the formation of inactive solid K2S2 and K2S blocks the diffusion process and their operation requires very high temperatures (>250°C) that need complex thermal management, thus increasing the cost of the process. Previous studies have struggled with solid precipitates and low capacity and the search has been on for a new technique to improve these types of batteries.

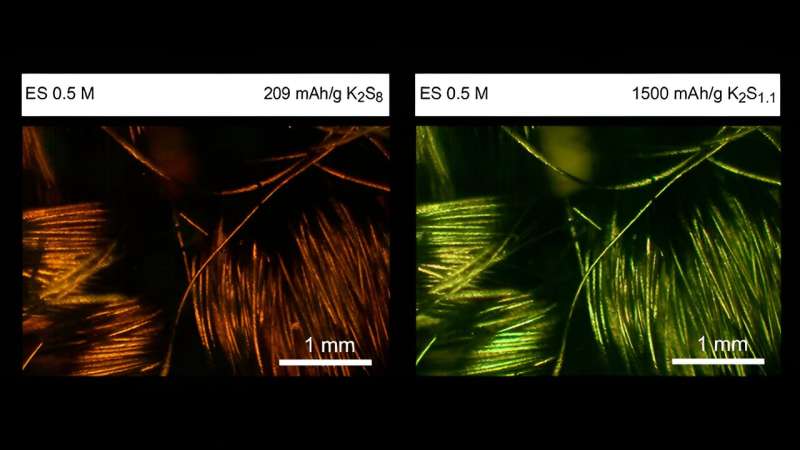

Yang’s group developed a new electrolyte, a solvent of acetamide and ε-caprolactam, to help the battery store and release energy. This electrolyte can dissolve K2S2 and K2S, enhancing the energy density and power density of intermediate-temperature K/S batteries. In addition, it enables the battery to operate at a much lower temperature (around 75°C) than previous designs, while still achieving almost the maximum possible energy storage capacity.

“Our approach achieves nearly theoretical discharge capacities and extended cycle life. This is very exciting in the field of intermediate-temperature K/S batteries,” said the study’s co-first author, Zhenghao Yang, a Ph.D. student with Yang.

While the team is currently focused on small, coin-sized batteries, their goal is to eventually scale up this technology to store large amounts of energy. If they are successful, these new batteries could provide a stable and reliable power supply from renewable sources, even during times of low sun or wind. The team is now working on optimizing the electrolyte composition.