It’s not yet clear how the results of the European Parliament elections will influence the policies of the next European Commission. Among other important issues, this uncertainty is hanging over the bloc’s plans for going climate neutral by 2050.

But one thing is certain: Electricity from renewable sources will be a vital element in reaching Europe’s climate goals.

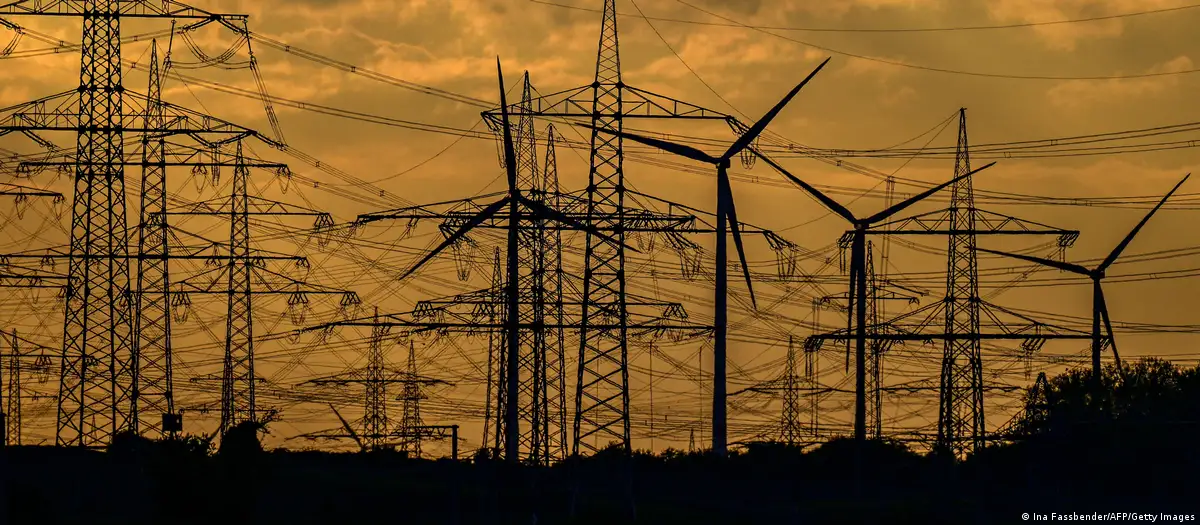

Some regions on the continent are especially suited for specific types of green energy production. But for the entire continent to benefit from this power, energy companies would need to build up an electricity grid across Europe incorporating these new technologies.

“European electricity infrastructure is already well-developed,” said Kadri Simson, an Estonian lawmaker who has been the EU’s energy commissioner since 2019, speaking with DW in May.

“We expect to electrify different sectors, which means that our electricity consumption will double. And that, of course, means we have to strengthen our electricity grid, too. We have to upgrade our electricity grid to allow more renewables to be installed,” she said, adding that Europe was only halfway there at present.

Wind in winter, solar in summer

European countries have different strengths when it comes to green power production. In the blustery north and on the North and Baltic seas, wind energy generates a lot of power. The sunnier south, meanwhile, is ideal for solar energy.

“Photovoltaic energy and wind energy complement each other well,” said Harald Bradke, the head of the Competence Center Energy Technology and Energy Systems at the Fraunhofer Institute in Karlsruhe, Germany. “Wind energy produces a lot of electricity in the winter months, and photovoltaics predominantly in the summer.”

The best methods to store electricity also differ according to geographical location. Pumped hydroelectric energy storage facilities, which function like huge batteries, are one good option. If more electricity is available than is being consumed at any one time, it’s used to pump water into a reservoir or up a mountain. When electricity is needed, the water is released again to drive the turbines that produce it.

“This type of storage exists above all in Scandinavia and Alpine countries, such as Austria, Italy and Switzerland,” said Bradke. “It can be used when demand for electricity exceeds what we can produce at that moment.”

More power lines are needed

Increased interconnectivity would make the supply of green electricity more efficient across the EU.

“Electricity would be cheaper because it would be obtained from the place where it can be produced at the lowest price,” said Bradke. What’s more, he added, it wouldn’t be necessary as often to “turn on expensive backup power stations that operate only a few hundred hours a year.”

Backup power plants, such as those driven by natural gas, are currently used to cover demand at peak times. But if Europe had a common electricity grid, this demand could be met by diverting electricity across the continent from places where it’s particularly cheap at the time to others where it is needed.

“Everyone would benefit,” said Bradke.

However, before that can occur, additional power lines must be built — not least in places like Germany. A lot of electricity is produced by wind energy in the country’s north, but this is mostly needed further south in the industrial heartland. Even though this imbalance has been recognized for years, the construction of the necessary power lines to bring the electricity to clients down south has been very slow.

“We are seven years behind on expanding our grid,” said Bradke. “We should have already had an additional 6,000 kilometers a long time ago.”

What’s holding back grid expansion?

Money isn’t the only problem in Germany. Many people don’t want to live near transmission towers, fearing the effect the power lines will have on their property value or their health. This has led some people to take legal action to prevent the construction of new projects.

But putting power lines underground isn’t a solution, either: it’s much more expensive, and as warm electrical cables can dry out the soil, they can also be detrimental for agriculture. Bradke said that means farmers are limited by what they can plant near buried electrical cables, if anything, and need compensation.

These problems in just a single country give an indication of the scale of the challenge of a Europe-wide grid. “If the idea is to build a transmission line through Germany to allow electricity to flow from France to Poland, acceptance by the local population is likely to be lower than if we are talking about providing German electricity for Germany,” said Bradke.

€800 billion to build out electricity grid by 2030

Disputes about which country ends up being the bigger beneficiary are particularly likely when transmission lines cross borders, said EU energy commissioner Simson.

The solution to such disputes, she said, is often to finance these projects using EU funds. As a result, the rules for the construction of Trans-European Networks for Energy (TEN-E) have been changed to make it easier to access EU funds and speed up the work.

A study commissioned by the industrial lobby organization European Round Table for Industry has estimated that investments to the tune of some €800 billion ($863 billion) are needed in the electricity grid up to 2030. At the end of 2023, the European Commission itself put forward an action plan for the same time period costing an estimated €600 billion.

Simson said that might seem like a lot of money, but pointed out that current energy supplies also came at a price.

“Keep in mind that in 2022 alone, European consumers paid €600 billion to buy fossil fuels from third countries. So it might seem a massive investment need, but at the same time, fossil fuels are not coming for free, either,” she said.

Where would the money come from?

Some of the costs could be covered by private investors, said Bradke, pointing to the recent construction start of a power line between Germany and the UK to be financed solely with private funds.

“Major insurance companies and pension funds are very interested in investing in grid construction,” said Bradke, adding that “the revenue doesn’t need to be that high but secure in the long term.”

He stressed, however, that money isn’t the only important thing when enlarging a power grid. Just as vital is accurately assessing the actual need, he said. For example, what happens if fewer heat pumps or electric vehicles are used than planned? And what if electric cars act as mass power storage and feed electricity into the grid as well?

Bradke said that would result in less electricity being shared across the grid. “And that could mean that we have high-voltage lines standing around that aren’t needed at all,” he pointed out.

Simson said EU financing for enlarging the power grid comes from the funding instrument called the Connecting Europe Facility. “I strongly advocate that when the next multi-annual financial framework is designed, we should just strengthen this fund,” she said.

The current financial framework, which determines the EU budget, runs until 2027. Everything after that is in the hands of the next European Commission, and the recently elected European Parliament.