As traditional energy methods increase in cost and take their toll on the environment, Penn State researchers are turning to two underutilized renewable resources, the sun and outer space, for solutions to generate electricity and passively cool down structures.

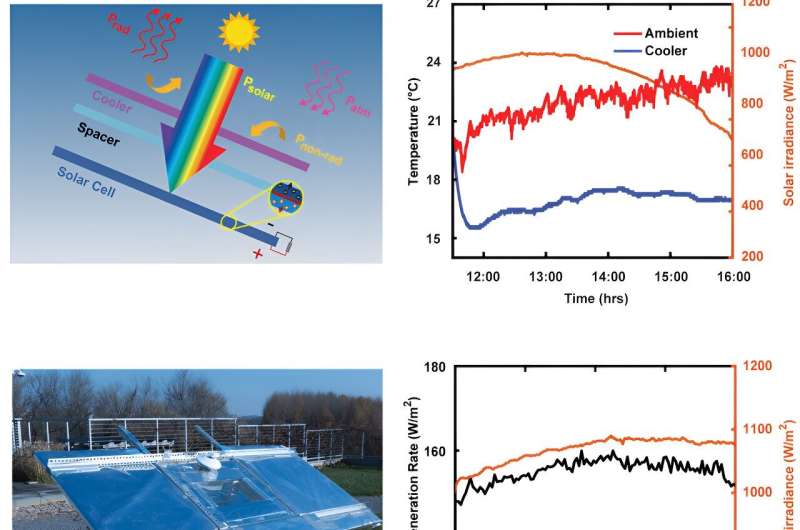

Led by Linxiao Zhu, assistant professor of mechanical engineering, the team developed and tested a dual cooling and power strategy that simultaneously harvests solar energy in a solar cell and directs heat away from Earth through radiative cooling. They published their energy solution, which is more efficient than either component on its own, on March 13 in Cell Reports Physical Science.

Radiative cooling works by sending infrared light directly into outer space instantaneously without warming the surrounding air. Zhu used a thermal camera to help explain the concept.

Invisible, heat-bearing infrared light can only be seen through a thermal camera, which uses color to display the temperature an object emits. A human body glows orange or red indicating a higher temperature, for example, while a window on a cold day is blue, indicating a lower temperature. Thermal infrared radiation, also known as blackbody radiation, is the energy people and objects shed as they cool down.

“In radiative cooling, the infrared light radiates from a piece of transparent, low-iron glass,” Zhu said. “The light bounces off the glass, passes through the atmosphere without warming the surrounding air, and lands in outer space, which we call the cold universe.”

This process, in turn, cools the surface of the radiative cooler. That cooling capacity can then be directed toward an object, like inside a building or refrigerator.

Daytime radiative cooling was invented a decade ago and is being developed as an emerging zero-carbon cooling method. As a doctoral student at Stanford University in 2014, Zhu served on the research team that first developed daytime radiative cooling.

“At night and during the day, the radiative cooler works as a 24/7 natural air conditioner,” said first author Pramit Ghosh, a doctoral student in mechanical engineering at Penn State. “Even on a hot day, the radiative cooler is cold to the touch.”

Underneath the radiative cooler, the researchers positioned a solar panel, so that during daylight hours, the sunlight passes through the transparent radiative cooler and is absorbed into the solar cell to generate electricity.

The researchers tested their system last summer at Penn State Sustainability Institute’s Sustainability Experience Center. They found the combined benefit of electricity generation and cooling from the dual harvesting system could surpass the electricity saving of a bare solar cell by as much as 30%. In other words, harvesting the resources together as a pair exceeds the performance of using either resource alone.

“Based on these experimental results, using the two harvesters together has the potential to significantly outperform a bare solar cell, which is a key renewable energy technology,” Zhu said.

The other benefit is the unit’s size: since the two harvesters are stacked, they take up minimal space on a rooftop or on the ground.

“At the same time and in the same place, we can exploit these renewable resources together, 24 hours a day,” Ghosh said.