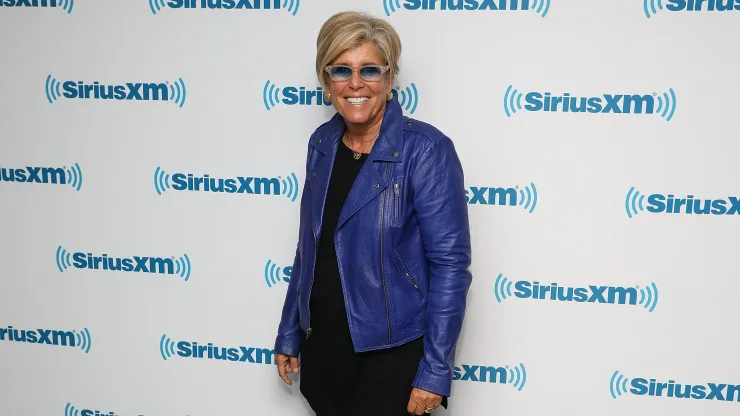

Suze Orman doesn’t want to make anyone feel dumb. This attitude, she says, is part of what made her a star in the world of personal finance, even if much of the advice she dispenses is standard stuff among money pros.

“They can relate to me because I speak Suze, speak a language that they can relate to,” Orman said on a recent appearance on “Who’s Talking to Chris Wallace?” on Max. “I never make them feel bad if they don’t understand something. And when they see me, they see hope, if Suze can do it starting at the age of 30, I can do it.”

But even if she doesn’t want you to feel bad, Orman — host of the “Women & Money (and Everyone Smart Enough to Listen)” podcast and co-founder of emergency savings firm SecureSave — does think you probably have to bone up on your finances.

When asked by Wallace what percentage of Americans she thought were financially illiterate, she said, “Truthfully, probably 95%.”

What does that mean?

“I tell somebody to do a Roth IRA. They don’t have a clue what I’m talking about. I ask somebody, what’s in your retirement account? … They don’t have a clue. They don’t have a will. They don’t have a trust. They don’t have a durable power of attorney for health care, or an advanced directive. They don’t know what a 529 plan is. They don’t understand.”

If you didn’t know a few of those terms, you’re not alone. Even Wallace admitted to not knowing all of them.

Of course, knowing this list of terms isn’t a make-or-break factor for financial literacy. But just in case you’re in Wallace’s camp, here’s a quick primer.

Saving for retirement

You know you have to save for retirement, but how do you do it? Usually, your best bet is investing your money through an account that gives you a tax break in exchange for saving.

So-called “traditional” accounts, including 401(k)s and individual retirement accounts, give you a tax break up front. Every dollar you invest in them counts against your taxable income for the year you invested. In exchange for this benefit, you’ll owe tax on the money when you withdraw it in retirement.

Roth versions of these accounts work in reverse. Because you fund these accounts with money you’ve already paid taxes on, your contributions don’t count against your taxable income. But provided you’re 59½ and have held the account for at least five years, money you withdraw in retirement — including your earnings — is tax-free.

Which account is right for you depends on your personal financial situation, but, in general, Orman tends to favor Roth accounts, due to the flexibility of withdrawals the accounts afford you in retirement.

Estate planning

A will, a durable power of attorney and an advanced directive are all part of the world of estate planning.

Even if you don’t think you have much in the way of assets, it’s wise for you to have an estate plan for one reason: If you don’t decide how to distribute your money and possessions in the case of your death, the government will.

A will, which designates how you want your assets distributed after you die, is the easiest of these documents to draw up. Templates can be found for free on websites such as LawDepot.com.

“A will is a simple slam dunk for most people,” Sheryl Garrett, a certified financial planner and founder of the Garrett Planning Network, told CNBC last year.

This form allows you to appoint an executor of your estate, list who gets what when it comes to your assets and name a guardian if you have dependent children.

Powers of attorney and advance directives lay out your wishes and allow you to designate who can make health care and financial decisions on your behalf in the event that you become incapacitated.

A trust, similar to a will, is an estate planning tool that allows you to transfer property and wealth to others. These are generally considered more useful if you have a particularly complicated estate, such as if you own real estate you’re hoping to pass down in multiple states.

Depending on your situation, a combination of some or all of these documents may make sense. And even the most financially literate among us would be wise to consult with an attorney who specializes in estate planning.

Saving for education

So-called 529 plans (nicknamed after their Internal Revenue Service code) are tax-advantaged investment vehicles geared toward people who want to save for a child’s education. Contributions to these accounts are made with after-tax money, but investments in them grow free from federal or state tax.

To get this tax treatment, you’ll have to withdraw the money to put toward qualified education expenses, which include not just college tuition, but costs for primary and high school, as well as trade school and apprenticeship expenses.

Some states offer an upfront tax deduction or credit for contributions as well. You can contribute to any state’s plan — and each plan comes with different investing options — but you’ll generally only receive tax benefits, if they’re offered, by investing in your home state’s plan.

The bottom line: ‘Don’t feel dumb’

Remember: not knowing any one particular money term doesn’t make you financially illiterate — especially since financial concepts aren’t taught in school.

“It should be mandatory that you can’t graduate high school and not understand how student loans work,” Orman said. “It should be mandatory that you understand what compounding interest means and how your youth contributes to millions of dollars in the long run.”

And if not knowing this stuff makes you feel stupid, you’re once again in good company.

“You only made me feel really dumb in a couple of areas,” Wallace told Orman.

“Don’t feel dumb,” Orman said. “Come to me.”

Don’t have Suze Orman on speed dial for your financial questions? Consider chatting with a financial advisor.