Forty-six years in deep space have taken their toll on NASA’s twin Voyager spacecraft. Their antiquated computers sometimes do puzzling things, their thrusters are wearing out, and their fuel lines are becoming clogged. Around half of their science instruments no longer return data, and their power levels are declining.

Still, the lean team of engineers and scientists working on the Voyager program at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory are taking steps to eke out every bit of life from the only two spacecraft flying in interstellar space, the vast volume of dilute gas outside the influence of the Sun’s solar wind.

“These are measures that we’re trying to take to extend the life of the mission,” said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager at JPL, in an interview with Ars.

Voyager’s instruments are studying cosmic rays, the magnetic field, and the plasma environment in interstellar space. They’re not taking pictures anymore. Both probes have traveled beyond the heliopause, where the flow of particles emanating from the Sun runs into the interstellar medium.

“These two spacecraft are still operating, still returning uniquely valuable science data, and every extra day we get data back is a blessing,” Dodd said.

While spacecraft engineers love redundancy, they no longer have the luxury of backups on the Voyagers. That means, in any particular section of the spacecraft, a failure of a single part could bring the mission to a halt.

“Everything on both spacecraft is single-string,” Dodd said. “There are not any backup capabilities left. In some cases, we powered off stuff to save power, just to keep the instruments on.”

Problem-solving from more than 12 billion miles away

Over the weekend, ground controllers at JPL planned to uplink a software patch to Voyager 2. It’s a test before the ground team sends the same patch to Voyager 1 to resolve a problem with one of its onboard computers. This problem first cropped up in 2022, when engineers noticed the computer responsible for orienting the Voyager 1 spacecraft was sending down garbled status reports despite otherwise operating normally. It turns out the computer somehow entered an incorrect mode, according to NASA.

Managers wanted to try the patch on Voyager 2 before transmitting it to Voyager 1, which is flying farther from Earth, deeper into interstellar space. That makes observations of the environment around Voyager 1 more valuable to scientists.

At the same time, engineers have devised a new way to operate the thrusters on both Voyager spacecraft. These small rocket engines—fired autonomously—are necessary to keep the main antenna on each probe pointed at Earth. There’s a buildup of propellant residue in the narrow lines that feed hydrazine fuel to the thrusters. NASA says the buildup is “becoming significant” in some of the lines, so engineers beamed up fresh commands to the spacecraft in the last few weeks to allow the probes to rotate slightly further in each direction before firing the thrusters.

This will result in the spacecraft performing fewer, longer firings, each of which adds to the residue in the fuel lines. The downside of this change is that science data transmitted back to Earth could occasionally be lost, but over time, the ground team concluded the plan would allow the Voyagers to return more data, NASA said.

With these steps, engineers expect the propellant inlet tubes won’t become completely blocked for at least five more years, and “possibly much longer,” NASA said. There are other things engineers could try to further extend the lifetime of the thrusters.

“This far into the mission, the engineering team is being faced with a lot of challenges for which we just don’t have a playbook,” said Linda Spilker, Voyager project scientist at JPL, in a statement. “But they continue to come up with creative solutions.”

Dodd told Ars the thruster issue is probably the most serious problem facing the Voyager spacecraft. In 2017, engineers started switching the Voyager probes to a backup set of thrusters after their primary rocket jets showed signs of degradation. Both Voyagers are now fully on backup propulsion to control their orientation, but they have plenty of fuel left for another 10 to 15 years.

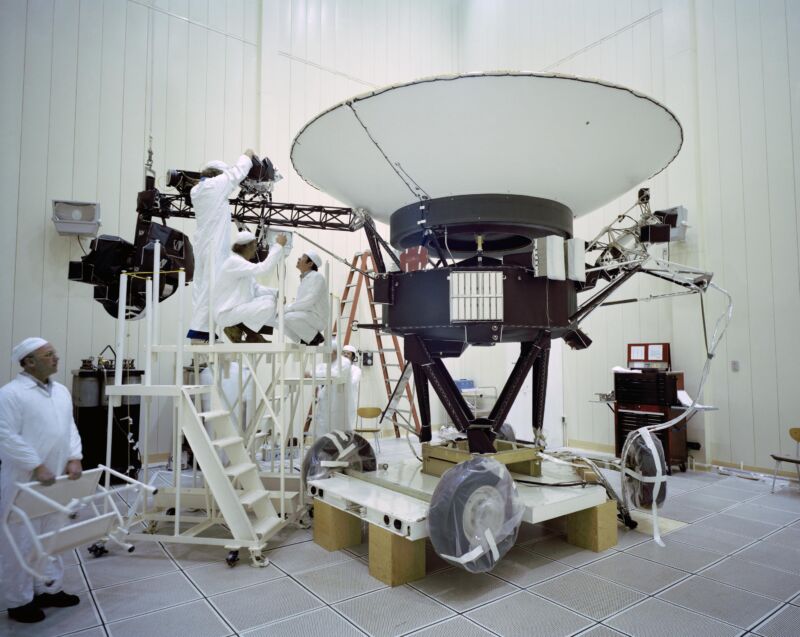

The Voyager probes launched two weeks apart in 1977 and took different routes out of the Solar System. Voyager 1 flew by Jupiter and Saturn, then took a more speedy trajectory into interstellar space, while Voyager 2 encountered Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune on its outbound journey.

Both spacecraft run off nuclear batteries, which convert heat from decaying plutonium into electricity. They generate a little less power each year—a decline of about 4 watts annually, according to Dodd—and eventually will not produce enough electricity for critical spacecraft systems. Late in this decade, officials anticipate a scenario where they will have to turn off the Voyager science instruments one by one.

But overall, the power situation is stable and predictable. Earlier this year, engineers bypassed a voltage regulator on Voyager 2 to allow the spacecraft to draw on more power. The decision means ground controllers will not have to shut off one of Voyager 2’s five remaining science instruments until 2026, after previously expecting to deactivate one of the instruments this year. Dodd said ground teams will do the same with Voyager 1, which only has four active instruments, and therefore uses less power.

If you only look at the power situation, the Voyagers should make it until 2030, and maybe slightly longer, before the decay of the plutonium power source forces NASA to switch off all their science instruments.

“The transmitter takes about 200 watts of power, so once we get down to that level of power, that will be the end of the mission,” Dodd said.

Even when they stop working, NASA’s Voyagers will continue on to the stars.

“A lot of things could break before we run out of power,” she told Ars. “Just like this thruster issue sort of popped up, there are a lot of other issues that could pop up and cause a mission to fail.”

Because of their distances, the Voyagers can only communicate through the largest 230-foot (70-meter) dish antennas in NASA’s Deep Space Network, or by arraying multiple smaller antennas together to detect the faint signals coming from the spacecraft. Voyager 1 is currently located more than 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) from Earth, about four times greater than the average distance of Pluto. Voyager 2 is a few billion miles closer.

NASA still makes contact with the Voyagers daily, Dodd said. But it’s all done with a small team of about a dozen “full-time equivalent” employees, and only about half of those are fully devoted to the Voyager program. The others share their time on other NASA projects.

At 46 years in space, the Voyagers are NASA’s longest-lived mission, and the fact that they’ve reached this longevity exploring the Solar System’s outermost frontier makes their accomplishments all the more impressive.

“They’ve overcome lots of issues, and the engineers have been very clever in overcoming those issues,” Dodd said. “I think the focus now is let’s get to 50 and have the biggest party we can.”