Hydrogen is viewed as a promising alternative to fossil fuel, but the methods used to make it either generate too much carbon dioxide or are too expensive. Rice University researchers have found a way to harvest hydrogen from plastic waste using a low-emissions method that could more than pay for itself.

“In this work, we converted waste plastics—including mixed waste plastics that don’t have to be sorted by type or washed—into high-yield hydrogen gas and high-value graphene,” said Kevin Wyss, a Rice doctoral alumnus and lead author on a study published in Advanced Materials. “If the produced graphene is sold at only 5% of current market value—a 95% off sale!—clean hydrogen could be produced for free.”

By comparison, “green” hydrogen—produced using renewable energy sources to split water into its two component elements—costs roughly $5 for just over two pounds. Though cheaper, most of the nearly 100 million tons of hydrogen used globally in 2022 was derived from fossil fuels, its production generating roughly 12 tons of carbon dioxide per ton of hydrogen.

“The main form of hydrogen used today is ‘gray’ hydrogen, which is produced through steam-methane reforming, a method that generates a lot of carbon dioxide,” said James Tour, Rice’s T. T. and W. F. Chao Professor of Chemistry and a professor of materials science and nanoengineering. “Demand for hydrogen will likely skyrocket over the next few decades, so we can’t keep making it the same way we have up until now if we’re serious about reaching net zero emissions by 2050.”

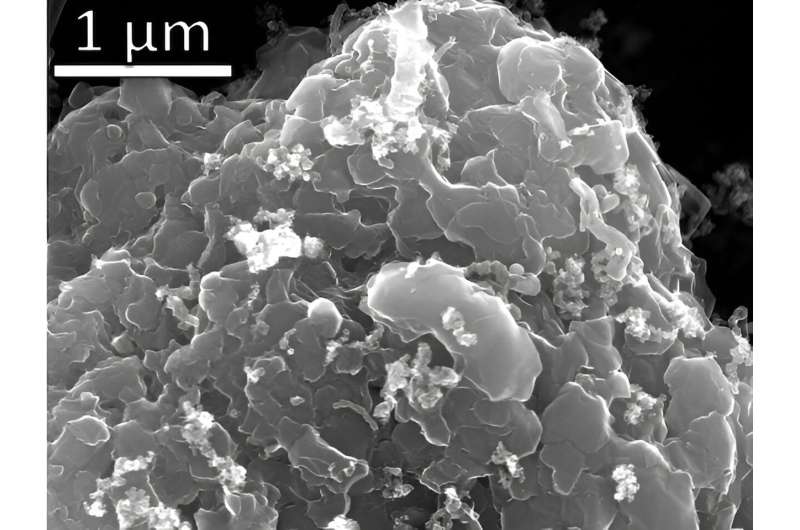

The researchers exposed plastic waste samples to rapid flash Joule heating for about four seconds, bringing their temperature up to 3,100 degrees Kelvin. The process vaporizes the hydrogen present in plastics, leaving behind graphene—an extremely light, durable material made up of a single layer of carbon atoms.

“When we first discovered flash Joule heating and applied it to upcycle waste plastic into graphene, we observed a lot of volatile gases being produced and shooting out of the reactor,” Wyss said. “We wondered what they were, suspecting a mix of small hydrocarbons and hydrogen, but lacked the instrumentation to study their exact composition.”

Using funding from the United States Army Corps of Engineers, the Tour lab acquired the necessary equipment to characterize the vaporized contents.

“We know that polyethylene, for example, is made of 86% carbon and 14% hydrogen, and we demonstrated that we are able to recover up to 68% of that atomic hydrogen as gas with a 94% purity,” Wyss said. “Developing the methods and expertise to characterize and quantify all the gases, including hydrogen, produced by this method was a difficult but rewarding process for me.

“I am glad that techniques I learned and used in this work—specifically life-cycle assessment and gas chromatography—can be applied to other projects in our group. I hope that this work will allow for the production of clean hydrogen from waste plastics, possibly solving major environmental problems like plastic pollution and the greenhouse gas-intensive production of hydrogen by steam methane reforming.”