The number of workers looting their retirement savings is escalating.

In the second quarter, the tally of folks taking hardship withdrawals from their 401(k) was up 12% compared to the first three months of the year and leapt 36% year over year, according to a new survey from Bank of America, which tracks about 4 million clients’ employee benefit programs.

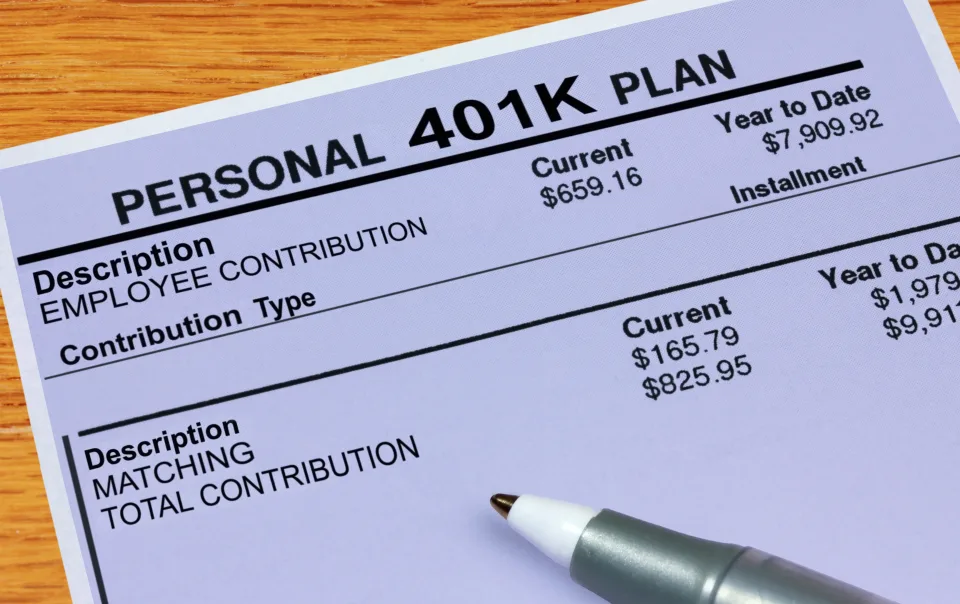

Borrowing from retirement savings was also up. The percentage of 401(k) participants who got a loan from their workplace plan stash in the second quarter was 2.5%, up from 1.9% in the first three months of the year.

Experts are worried that people are beginning to treat these accounts as savings rather than retirement accounts and may even be spurred to do more in the future due to a change in the law that could end up having the opposite effect than intended.

“I fear the public will go in and out of their retirement plans,” Steve Parrish, adjunct professor and co-director of the Center for Retirement Income at The American College of Financial Services, told Yahoo Finance. “The current increase in withdrawals and loans may be an indicator of movements to come.”

‘Understand the consequences’

According to the Bank of America survey, the average worker hardship withdrawal from a 401(k) plan in the second quarter of the year was $5,050, on par with the average withdrawal of $5,100 in the first quarter.

The average loan per participant was $8,550. Generations with the highest percentage of loans outstanding are Gen X (22%) followed by millennials (14.5%).

Withdrawals, of course, are worse for savers because not only is that money gone, robbing your future self, the withdrawal triggers some hefty taxes and penalties.

A withdrawal from your 401(k) account is typically taxed as ordinary income. Also, you’ll pay a 10% early withdrawal penalty before age 59½, unless you meet one of the IRS exceptions. These include certain medical expenses, qualified tuition payments, and up to $10,000 for first-time homebuyers. Some employer plans, too, will allow a non-hardship withdrawal.

With a loan, you borrow money from your retirement savings and pay it back to yourself, usually within five years, with interest — the loan payments and interest go back into your account.

One caveat: If you leave your current job, you might have to repay your loan in full within short order. When you can’t repay the loan, it’s considered defaulted, and you’ll owe both taxes and a 10% penalty if you’re under 59 ½.

“Yes, you can access your accounts, but you need to understand the consequences,” Parrish said.

‘Prioritizing short-term expenses over long-term saving’

There are myriad reasons for pulling money from these accounts ranging from paying off high interest credit card debt — interest rates on credit cards are at near 40-year highs — to medical bills, home improvements, buying a car or a house, or plainly to make ends meet right now.

“In 2023, the rise in living costs and short-term financial needs are forcing participants to dip into their retirement savings,” Lisa Margeson, managing director of external affairs, retirement research, and insights at Bank of America, told Yahoo Finance.

The findings also match other recent data on retirement account raids.

A 2023 survey by the nonprofit Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies (TCRS) in collaboration with the Transamerica Institute, published in July, reported that nearly 4 in 10 (37%) of workers have taken a loan, early withdrawal, and/or hardship withdrawal from their 401(k) or similar plan or IRA. That includes a hefty 28% of Gen Z workers who have taken a hardship withdrawal, 24% of millennials, 19% of Gen X, and 12% of boomers, according to the report.

Last year, 2.8% of 401(k) plan participants took a hardship withdrawal, a record high, up from 2.1% in 2021 and 1.9% in 2018, according to a recent Vanguard report.

Said Lorna Sabbia, head of retirement and personal wealth solutions at Bank of America: “This year, more employees are understandably prioritizing short-term expenses over long-term saving.”

The question is: Will the siphoning continue once inflation cools? Maybe not.

The SECURE 2.0 Act that passed at the end of 2022 created six new ways to access retirement accounts penalty-free before age 59 ½ as a way to encourage workers to contribute more by making it easier to tap those funds if needed without penalty.

Still, Parrish said he “wouldn’t draw too big a conclusion from short-term data. It suggests that employers may want to assure they provide at least some education to employees about their plans.”