Industrial metals are universally viewed as the backbone of the modern economy. Whether it’s the buildings we live in, the cars we drive, or the mobile device we’re browsing with, virtually everything we see or consume is made of some type of metal.![]()

Copper is used in wiring due to its conductivity, aluminum has uses ranging from drink can production to aerospace engineering because of its light weight and corrosion resistance, while steel, which is made of iron, is equally common with applications ranging from cutlery production to automobile construction.

In recent years, some less common metals have also become increasingly popular for playing key roles in the global energy transition. Lithium, a soft, light metal, is now the major ingredient in the rechargeable batteries found in phones and electric vehicles. Nickel, primarily used to make stainless steel, is also commonly found in battery chemistries. Others like cobalt and manganese are found to be crucial for battery performance, hence their label as “critical minerals”.

In 2021, the world produced roughly 2.8 billion tonnes of metals to feed these industrial applications, the US Geological Survey estimates. While that may have been enough to satiate short-term demands, the future would likely be marred by a significant shortage in some (or all) metals.

Below we list out four major forces behind the looming metals supply crunch:

#1 The global energy transition

Electrification, decarbonisation and renewables — these are some of the most common buzzwords associated with our mission to tackle climate change. No matter how you phrase it, the global transition to clean energy will need lots of metals to succeed, given the enormous scale of infrastructure required.

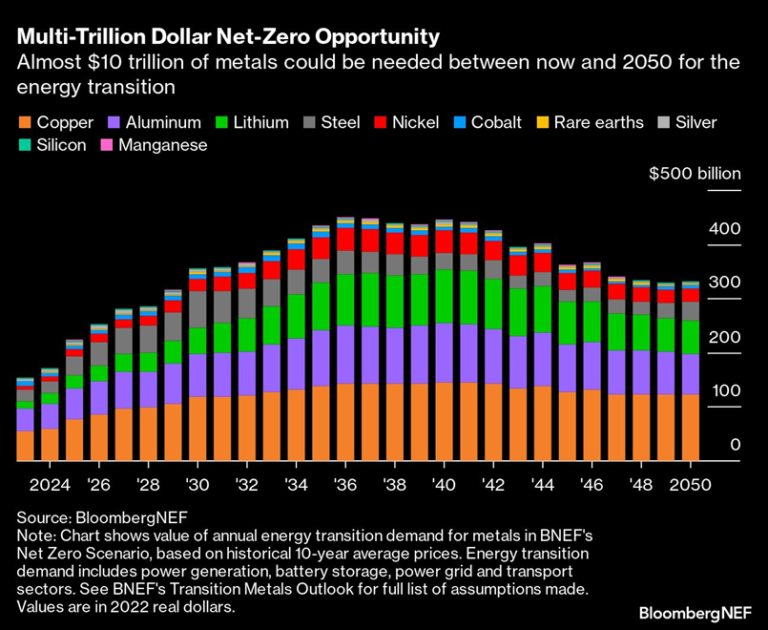

BloombergNEF estimates that getting to our net zero climate targets could require almost $10 trillion worth of metals between now and 2050, with annual demand peaking at close to $450 billion in the mid-2030s.

“While steel and aluminum are expected to see the most demand growth in terms of absolute volume, copper is set to be the most valuable opportunity, with an estimated $3.4 trillion of the red metal needed to avert climate disaster,” BloombergNEF said.

Likewise, the IMF says that the demand boom triggered by the energy transition could lead to more than a fourfold increase in the value of metals production, totalling $13 trillion over the next two decades for copper, nickel, lithium and cobalt.

In particular, battery metals cobalt and lithium will experience the greatest consumption growth, increasing by four-fold and seven-fold respectively by 2050, according to IMF forecasts. Nickel could even see demand rise close to ten times during this decade, Bloomberg estimates.

To meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, International Energy Agency data shows that sectors contributing to the green energy transition will be responsible for over 45% of the total copper demand, 61% of the nickel demand, 69% of the cobalt demand, and a whopping 92% of lithium demand by 2040.

This unprecedented level of consumption would eventually overwhelm our existing supply of metals. Should production fail to catch up, sooner or later, the world could be facing a severe metals shortage that endangers the energy transition.

#2 Struggling producers

Unfortunately the metals powering our economy don’t grow on trees; they have to be mined from the Earth. In recent years, a new problem has emerged within the mining industry where the major contributors to supply are struggling to keep up with soaring demand.

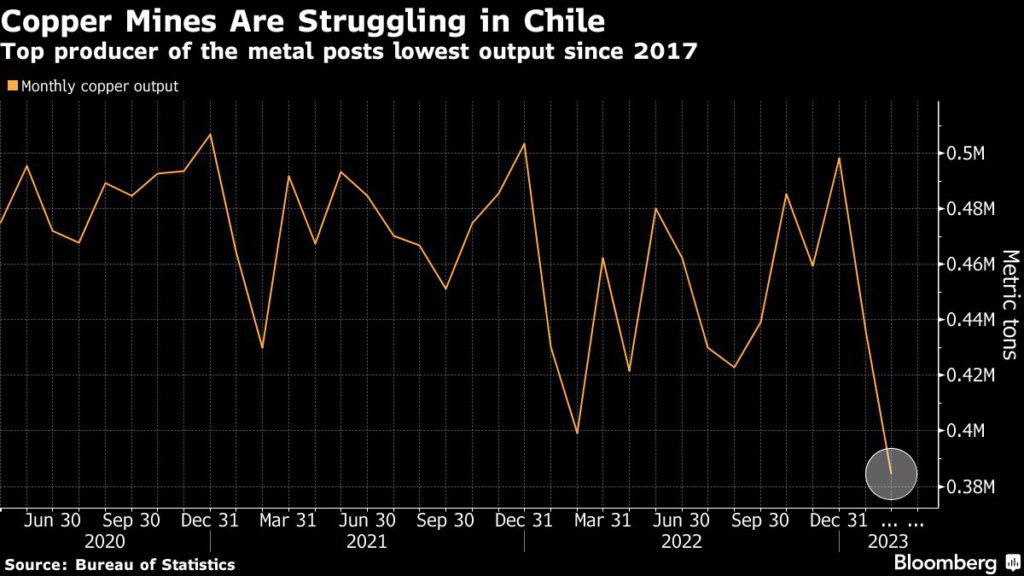

Take copper, for example, the world’s leading producer Codelco recently said it has been hampered by multiple operational setbacks and project delays, causing its monthly output to hit its lowest in six years.

The Chilean state-owned company is already coming off a down year in 2022, during which its copper production tumbled 11% to 1.45 metric tons. Things aren’t getting better for Codelco anytime soon either.

The company warned that the output woes of 2022 will only get worse this year as it “strives to tap new areas of its aging deposits after decades of underinvestment.” This year, Codelco is again expecting production to fall as much as 7%, forecasting output of between 1.35 million and 1.42 million metric tons.

Meanwhile in Peru, the second biggest producer, even the largest miners are coming to terms that their copper operations could be imperiled by political unrest at any time. An industry group estimates that this year’s violent protests could put as much as 30% of the nation’s production at risk.

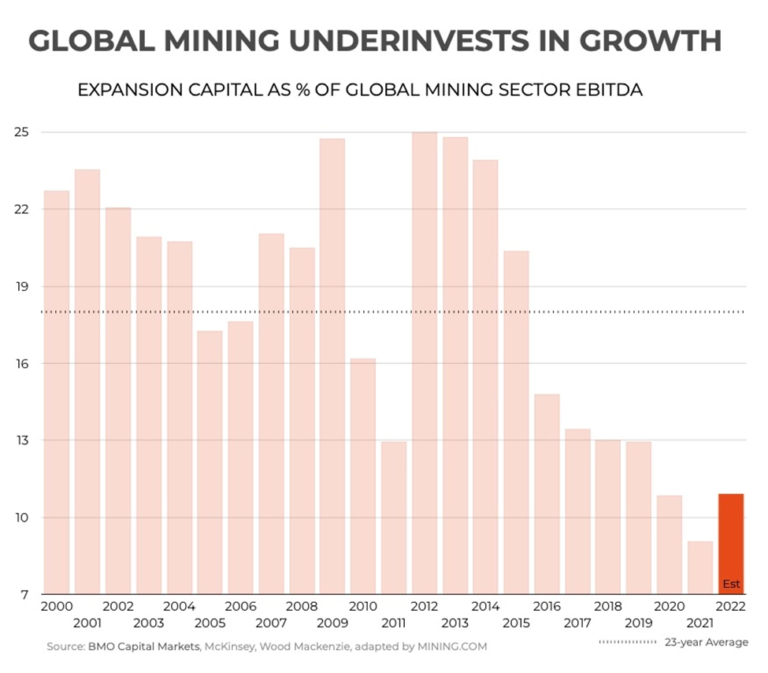

Even if all existing mine operations around the world are operating smoothly and to their maximum potential, supply growth is still being held down by the lack of investment in new mining projects.

“Global mining’s enthusiasm for brown and greenfield projects has fizzled over the last decade despite near universal agreement that in the coming decades demand for metals and minerals will boom due to the green energy transition,” a new report by BMO Capital Markets recently found.

According to BMO, while companies “have started to talk more openly about investment,” so far they are “doing little about it”.

Over the past 20 years, expansion capital spending across the industry has typically run above 20% of EBITDA, but now, this metric has slipped to around 10% over the past couple of years, the report finds.

“Given the timeline to bring a mine to market, this lack of investment is storing up issues for later in the decade, where balances look incrementally tighter,” the authors of the BMO report warned.

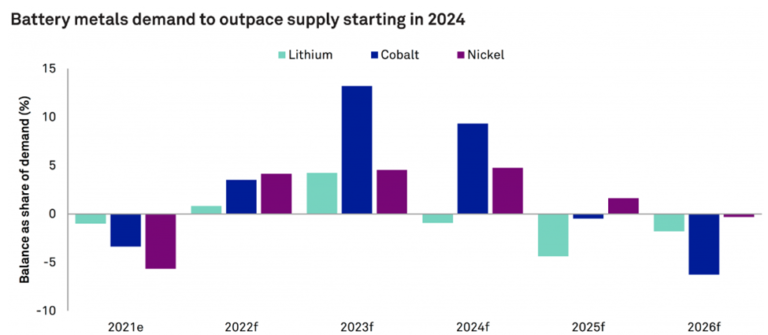

An analysis by S&P Global found that the increasing consumption will outstrip the mining industry’s ability to ramp up supply, resulting in commodity deficits as early as 2024.

Trafigura — the world’s biggest copper trader — warned that supply challenges could extend beyond mining, as there are also risks that Western economies will fall short in their efforts to boost metals refining and processing.

“Metal processing has been concentrated in China for the past three decades, and it now has to expand out of that footprint for many reasons,” Trafigura CEO Jeremy Weir said in a Bloomberg interview. “The problem is there’s a long lead time for these things.”

#3 Macroeconomic conditions

Further compounding the issue are the macroeconomic conditions miners are having to navigate through to keep their metals operations running profitably. For most of 2022, the industry has faced decades-high inflation driven by supply chain issues arising from the Covid-19 pandemic.

S&P Global expects the deteriorating global macroeconomic conditions to persist in 2023, representing a downside risk to the metals and mining sector as many commodity prices slide and equity markets weaken.

“Producers will be hit by narrowing margins, while exploration activity will slow amid tighter financing conditions,” the New York-based analytics firm says in its report.

According to S&P, lower activity levels through 2023 will reinforce the mining industry’s importance in the global energy transition.

This is especially the case for commodities deemed critical to the global decarbonisation effort, as S&P forecast supply constraints across battery metals to emerge as early as 2024, with “demand expanding markedly on rising EV sales, the shift towards renewable energy technologies, and related transmission and distribution requirements.”

#4 Sanction impacts

Western governments have been very vocal about establishing critical minerals strategies and forming alliances to achieve their climate change ambitions. In that regard, actions taken to isolate one of the most resource-rich nations in the world do seem rather counterproductive.

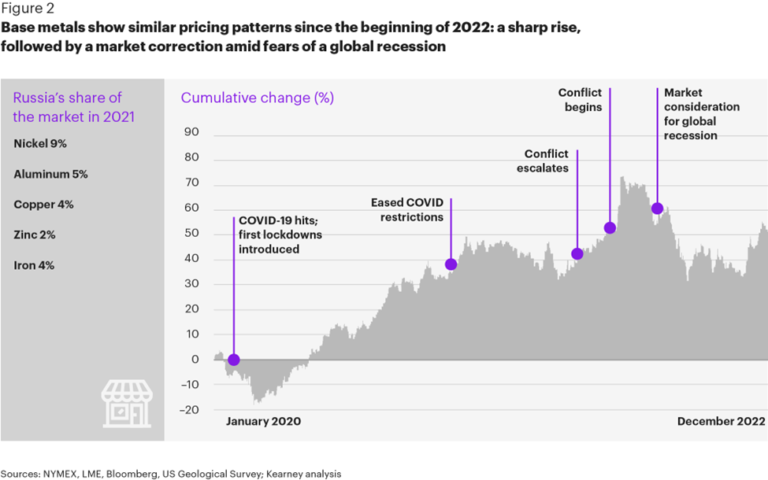

According to management consultants at Kearney, the preoccupation with supply shocks has obscured how sanctions against Russia are affecting the metal markets. As of November 2022, Russia has been hit with more than 12,000 sanctions — four times the number imposed on the next most penalized country Iran.

Since early 2022, the five base metals that Russia produces have experienced sharp price increases. Continued supply disruptions are likely to keep prices climbing for some of them, the Chicago-based firm predicts.

For example, nickel, for which Russia accounts for roughly 10% of world output, is likely to see significant long-term increases thanks to the growing demand for EVs and non-fossil-based energy and the metal’s importance in electronics and steel production.

“While Russia’s biggest commodity players may be the most prominent of the sanctioned entities, these sanctions can affect far more than the sale of their commodities,” Kearney’s analysis finds.

Consumers have also felt the effects with European and US companies suspending their Russian operations, the firm says. Among those are the leading logistics companies, which transport solid commodities throughout the globe.

The bans pinch the supply of spare parts for aircraft and heavy machinery, including hauling and loading equipment, tractors, assembly line machinery, and drilling equipment. The resulting crunch in equipment availability is already dampening activity across many sectors such as mining.

“Whether they involve spare parts or new technologies, sanctions could have longer-term consequences for everything from the sustainability of mining operations to the functioning of the manufacturing base,” Kearney predicts.