Nigeria’s central bank has extended the timeline to swap out its old currency for redesigned notes after the change triggered a cash shortage

ABUJA, Nigeria — Nigeria’s central bank has extended the timeline to swap out its old currency for redesigned notes after the change triggered a cash shortage, forcing businesses to close and leaving millions unable to withdraw their money.

The Central Bank of Nigeria announced late Monday that the old notes of 200 naira (43 U.S. cents), 500 naira ($1.08) and 1,000 naira ($2.16) will remain legal tender until Dec. 31. Bank spokesman Isa Abdulmumin said the extension was meant to comply with a directive from the country’s Supreme Court, which ruled that the program’s implementation broke the law.

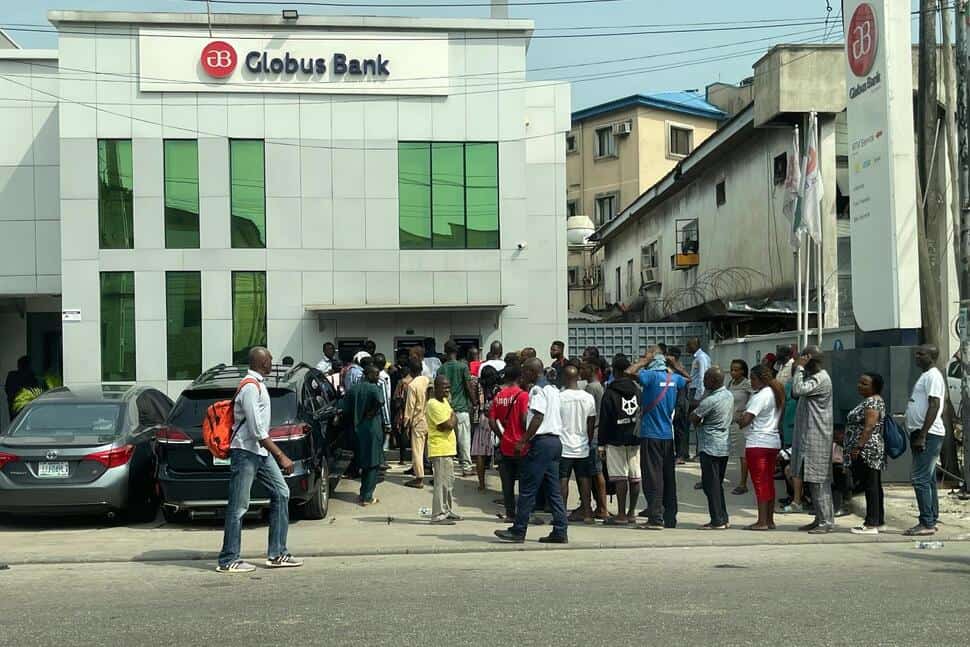

On Tuesday, both old and redesigned notes were still not available for thousands queued at banks in Nigeria’s capital of Abuja. There has been a cash shortage since early February because not enough redesigned notes have been printed to replace the old ones in the cash-reliant country.

Analysts have accused authorities of poorly implementing the policy in Africa’s largest economy, where digital payment services are usually not reliable and only 45% of adults have a bank account, according to the World Bank.

The cash crisis has cost the Nigerian economy an estimated 20 trillion naira ($43 billion) because of “the crippling of trading activities, the stifling of the informal economy and contraction of the agricultural sector,” the Lagos-based Center for the Promotion of Private Enterprises said in a statement.

The organization said the situation has further squeezed people and businesses in the country where 63% of the population is poor and 33% is unemployed.

The loss of a major payment method “affects business transactions; you cannot buy and you cannot sell, especially for the segments of the economy that are driven largely by cash,” said Muda Yusuf, director of the center.

Policymakers said the currency changeover would curb inflation, fight money laundering and limit the use of cash to buy votes in Nigeria’s general elections, which started last month.

But most of the program’s desired results have not been achieved because of how badly it was implemented, according to Tunde Ajileye, a partner at Lagos-based SBM Intelligence firm.

“The political goal is to attempt to stifle the flow of cash to make vote-buying more difficult. That was achieved. However, the political class moved from buying voters to influencing INEC (electoral body) officials,” Ajileye said. “The consequences have been dire … so it is a lose-lose situation.”