Critics blamed overly generous unemployment benefits for a labor shortage afflicting businesses and argued that ending the extra assistance would force many Americans to go back to work.

But that didn’t happen.

States that ended a federal boost to jobless benefits early experienced virtually the same drop in unemployment this summer as states that maintained the extra assistance, according to a new analysis.

From June to August, the jobless rate in states that cut off a weekly $300 federal supplement to state unemployment benefits dipped by 0.25%, compared with a 0.26% drop in states that continued the benefit, according to an analysis of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics by the Century Foundation, a progressive think tank.

Last year, the federal government enhanced and expanded unemployment benefits to help Americans weather the economic shock of the COVID-19 pandemic, which shuttered businesses, crippled the leisure and transportation industries and erased 22.4 million jobs.

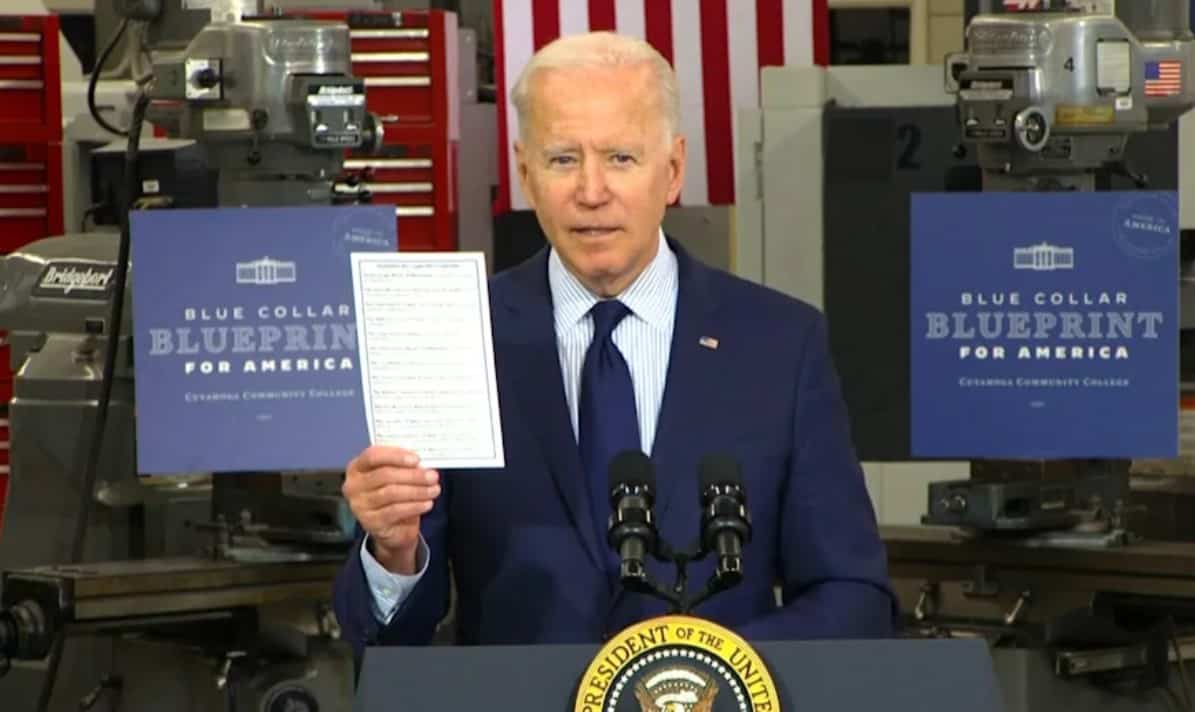

The federal CARES Act originally gave an additional $600 a month to those receiving unemployment benefits. The supplement was later cut in half, and President Joe Biden’s American Rescue Plan, passed in March, gave the benefit boost a Sept. 6 cut-off date.

But in the spring, 26 states said they would cut the extra $300 a week in federal assistance before it officially ended, as some employers and Republican lawmakers said the additional money was discouraging people from returning to work.

“The hypothesis Republican governors and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce offered, that unemployment benefits were what was holding back hiring … has been disproved, at least so far,” said Andrew Stettner, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, who conducted the data analysis.

Stettner reviewed data from 24 states, excluding Indiana and Maryland which intended to end the federal supplement early but were ordered to continue providing the benefit following legal challenges.

A muddied employment picture

Jobless claims plunged 41.6% in the states that ended the federal supplement early, as compared to a 20.9% decline in states that did not, said Aneta Markowska, managing director and chief financial economist for Jefferies LLC.

While those states did see a bigger decline by one metric, ultimately their unemployment rate dipped by nearly the same rate as those that continued the extra benefits throughout the summer.

That’s because while states that ended the $300 check before September saw their employment rates rise faster than their peers in June, those rates then fell in late July and August, Markowska said.

The rise of the delta variant likely complicated the data in states that stopped the supplemental aid.

“It disproportionately hit states which withdrew,” Markowska said, “and may have led to a spike in quitting activity in those statesThis would explain why employment in those states was not stronger, even as more unemployed individuals moved into employment.”

Economists have disagreed about whether the federal boost to unemployment assistance stifled job searches, though many say most people would rather work than rely on benefits.

A paper published in May by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco found that if 7 of 28 people receiving the extra $300 were offered a job in a given month, only one would refuse the position because of the boosted benefit.

“Whether your benefits were going to end on Labor Day or whether they ended on July 4, people understand there’s no future in unemployment benefits,’’ Stettner said. “They understand their futures lie with going back to work.’’

But a Morning Consult survey in June found 13% of those getting unemployment benefits turned down job offers because of that assistance, while roughly that same number of recipients would probably accept a job by the end of this year.

Unemployment benefits a barrier?

When Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey announced his state would end the federal unemployment supplement as of July 10, he said in a statement that businesses were having difficulty filling important positions.

“We cannot let unemployment benefits be a barrier to getting people back to work,’’ he said.

But statistics don’t reveal why people do or do not return to work, some state officials say.

In Ohio, which ended the federal boost to unemployment benefits on June 26, the unemployment rate climbed from 5.2% in June to 5.4% in August, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The uptick might be due to more people actively looking for work but not immediately finding a job, Bill Teets, spokesman for the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, said in an email.

“Generally speaking, workforce participation has been increasing for a number of months,” he said, “and our number of continuing unemployment claims have also been trending downward for months. While combined these indicate we are in economic recovery, data can’t tell us the motivation for people reentering the workforce.”

Meanwhile, since Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds announced in May that extra federal pandemic-related assistance would end June 12, there’s been a 236% increase in the number of people who have visited the state’s employment offices, said Jesse Dougherty, spokesman for Iowa Workforce Development (IWD). Additionally, initial jobless claims in the state dropped from 8,362 in July to 7,754 in August.

“Iowa continues to have more open positions than it has available workers,” Dougherty said in an email.

South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem announced in May that her state would end the extra unemployment benefits. Marcia Hultman, the state’s labor and regulation secretary, noted at the time that businesses across the state said they would grow and expand if it wasn’t for a lack of workers.

“Ending these programs is a necessary step towards recovery, growth and getting people back to work,” Hultman said.

But eliminating the benefits did not move the state’s unemployment, which stood at 2.9% in June and remained at 2.9% in August.

South Dakota’s labor force had already largely recovered before the state ended federal unemployment benefits, Dawn Dovre, spokeswoman for the state’s Department of Labor and Regulation, said in an email.

“It has continued to improve since then,” she said. “Keep in mind, South Dakota never mandated a shutdown and remained open for business. Our unemployment rate has consistently been among the lowest in America as a result. We are currently third-lowest at 2.9%.”

Pandemic is key

Several factors may be preventing more people from returning to work, including a lack of childcare, Stettner said. And the slowed delivery of goods and parts are also affecting the economy.

Ultimately, control of the pandemic will likely be a key driver to getting people back on the job, he said.

“When we’ve seen progress around the pandemic that’s when we’ve seen the greatest progress in the economy,’’ he said, adding that the number of people returning to work increased when vaccines began to roll out in April.

Unemployment also began to dip at the end of last summer when more businesses began to reopen, he said. “These (declines) didn’t necessarily coincide with the benefits becoming less generous,’’ he said.

Many workers who were dissatisfied with their jobs have been exploring other options since the pandemic, said David Parsley, an economist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

“They’ve been away from their employment for more than a year due to the pandemic, and they are really thinking about what are my options,” Parsley said. “It’s not just a matter of not getting unemployment benefits,” Parsley said. “It’s what do I want to do with my life.”