Muse Group—owner of the popular audio-editing app Audacity—is in hot water with the open source community again. This time, the controversy isn’t over Audacity—it’s about MuseScore, an open source application which allows musicians to create, share, and download musical scores (especially, but not only, in the form of sheet music).

The MuseScore app itself is licensed GPLv3, which gives developers the right to fork its source and modify it. One such developer, Wenzheng Tang (“Xmader” on GitHub) went considerably further than modifying the app—he also created separate apps designed to bypass MuseScore Pro subscription fees.

After thoroughly reviewing the public comments made by both sides at GitHub, Ars spoke at length with Muse Group’s Head of Strategy Daniel Ray—known on GitHub by the moniker “workedintheory”—to get to the bottom of the controversy.

What’s MuseScore?

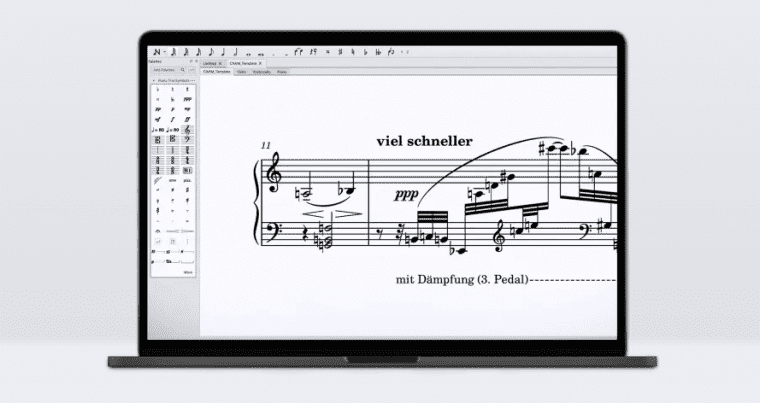

Before we can talk about how Muse Group got itself in trouble, we have to talk about what the MuseScore app itself is—and is not. The MuseScore application provides access to sheet music, including legitimate access to sheet music copyrighted and owned by large groups such as Disney.

It’s important to note that the application itself and the sheet music to which it provides access are not the same thing, and they are not provided under the same license. The application itself is GPLv3, but the musical works it enables access to via musescore.com have a wide variety of licenses, including public domain, Creative Commons, and fully commercial.

In the case of commercial, all-rights-reserved scores, Muse Group is not generally the rightsholder for the copyrighted work—Muse Group is an intermediary which has secured the rights to distribute that work via the MuseScore app.

According to Muse Group, MuseScore is the most popular application of its kind—it claims more than 200,000 musicians find scores on it every day, from a repository of more than 1,000,000 publicly available scores. It also claims more than 1,000 new scores are uploaded to the service each day.

What’s Muse Group’s beef with Xmader?

While Xmader did, in fact, fork MuseScore, that’s not the root of the controversy. Xmader forked MuseScore in November 2020 and appears to have abandoned that fork entirely; it only has six commits total—all trivial, and all made the same week that the fork was created. Xmader is also currently 21,710 commits behind the original MuseScore project repository.

Muse Group’s beef with Xmader comes from two other repositories, created specifically to bypass subscription fees. Those repositories are musescore-downloader (created November 2019) and musescore-dataset (created March 2020).

Musescore-downloader describes itself succinctly: “download sheet music from musescore.com for free, no login or MuseScore Pro required.” Musescore-dataset is nearly as straightforward: it declares itself “the unofficial dataset of all music sheets and users on musescore.com.” In simpler terms: musescore-downloader lets you download things from musescore.com which you shouldn’t be able to; musescore-dataset is those files themselves, already downloaded.

For scores which are in the public domain or which users have uploaded under Creative Commons licenses, this isn’t necessarily a problem. But many of the scores are only available by arrangement between the score owner and Muse Group itself—which has several important implications.

Just because you can access the score via the app or website doesn’t mean you’re free to access it anywhere, anyhow, or redistribute that score yourself. The distribution agreement between Muse Group and the rightsholder allows legitimate downloads, but only when using the site or app as intended. Those agreements do not give users carte blanche to bypass controls imposed on those downloads.

Further, those downloads can often cost the distributor real money—a free download of a score licensed to Muse Group by a commercial rightsholder (e.g., Disney) is generally not “free” to Muse Group itself. The site has to pay for the right to distribute that score—in many cases, based on the number of downloads made.

Bypassing those controls leaves Muse Group on the hook either for costs it has no way to monetize (e.g., by ads for free users) or for violating its own distribution agreements with rightsholders (by failing to properly track downloads).

What’s the OSS community’s beef with Muse Group?

In February 2020, MuseScore developer Max Chistyakov sent Xmader a takedown request—which Xmader republished as an issue on GitHub—for musescore-downloader. He declared that Xmader “illegally use[s] our private API with licensed music content.” Chistyakov goes on to state that much of the content in question is licensed to Muse Group by major publishers such as EMI and Sony, and that Xmader’s downloader violates those rightsholders’ rights.

Chistyakov then threatens that, if the repositories in question are not closed, he will have to “transfer information about you to our lawyers who will cooperate with Github.com and Chinese government to physically find you and stop the illegal use of licensed content.” (This cryptic reference to the Chinese government will come up again later.)

In June 2020, MuseScore’s Daniel Ray (aka workedintheory) responded to the GitHub issue “to see if we may be able to resolve this situation without need for further processes.” Ray discussed legal issues of copyright and distribution with Xmader and various Github users for several months. For the most part, those discussions were devoid of acrimony. In October 2020, Ray declared that he “gave ample time for response, but now must proceed with requesting takedown from GitHub.”

Unfortunately, this proved less simple than Ray imagined—while musescore-downloader facilitates unlicensed downloads of DMCA-protected works, it does not itself contain those works, which means GitHub itself can ignore DMCA takedown requests. This stalled takedown efforts at Github, and in the months-long absence of continued feedback from Muse Group, commenters on the GitHub thread declared themselves victorious, and the thread languished untouched from December 2020 to May 2021.

The dormant controversy returns

In May 2021, interest in the GitHub issue returned, possibly due to cross-referencing by GitHub user “marcan” from the telemetry pull request on the Audacity repository (that repository is also owned by Muse Group). In June, the musescore-downloader extension for Google Chrome was removed from the Chrome Web Store due to a trademark claim, and in July, freelance journalist Arki J. Kirwin-Muller (aka “kirwinia”) requested permission of all involved to quote their Github posts.

Kirwin-Muller’s request brought Ray out of the woodwork again, to offer further explanation of Muse Group’s side of the controversy. Ray states that musescore-downloader and musescore-dataset violate US Code Title 17, which regulates copyright enforcement in the US, linking directly to § 1201 (circumvention of copyright protection systems) and, more seriously, § 506 (criminal offenses).

Ray goes on to state that he has “hesitated” (for well over a year) in prosecuting these alleged offenses due in part to Xmader’s personal status. In addition to the potentially draconian legal penalties associated with Title 17 itself, Ray fears that criminal prosecution could result in Xmader being deported from his current country of residence.

Deportation, too, could be worse for Xmader than most—he is highly and publicly critical of the Chinese government and, in another Github repo, notes himself that he might one day be arrested for that criticism.

Ray winds up addressing Xmader directly, stating that he is “young, clearly bright, but very naive,” and asking, “do you really want to risk your entire life so a kid can download your illegal bootleg of the Pirates of the Caribbean theme for oboe?”

There are two obvious ways to interpret Ray’s closing question. Is it an earnest appeal, or is it a thinly veiled and very public threat? Most of the community appears to have opted for the latter.

It’s about the content, not the code

Before writing this piece, Ars spoke to Ray himself via phone. During our conversation, Ray came across as earnest and passionate about both music and open source software. Unprompted, he made clear that Muse Group has no issue with forking the code itself—in fact, the company encourages doing so; Ray expressed unconflicted understanding and appreciation of forks as a vital part of “how free software—I’m a free software guy specifically, and I suspect you know the difference—is done.”

Ray went on to point out that, when Muse Group first acquired MuseScore, none of the content was properly licensed—in short, MuseScore was a piracy hub. According to Ray, the original MuseScore was “on the verge of being shut down by music publishers and rights groups” when it was acquired by Muse Group. This becomes important both to explain Muse Group’s necessary due diligence in responding to musescore-downloader and also to his clumsily expressed concern for Xmader—even if Muse Group ignored musescore-downloader, the odds of rightsholders such as Sony, Disney, and BMI ignoring it once it comes to their attention seem close to nil.

We pressed Ray about licensing. We wanted to get a better idea of his—and Muse Group’s—true open source bona fides. One controversial aspect of Muse Group’s recent acquisition of open source audio editor Audacity involved a license change—from GPLv2 to GPLv3. Ray explained that the GPLv3 license change was necessary to allow incorporation of the VST3 digital signal processing library, which is itself licensed GPLv3.

Ray also explained that Muse Group reached out to all 117 individual contributors to the Audacity project to request permission for the license change. He said that more than 90 of those contributors responded and that every response was a “yes”—and the remaining contributions were easy enough to simply refactor.

A quick “sniff check” with git-blame makes this sound reasonable—roughly speaking, 99 percent of Audacity’s total code comes from only 30 people. As is the case with many open source projects, the majority of individual contributors are “drive-bys” who write a few lines of code to solve an immediate problem, then disappear. In addition, Audacity’s most prolific contributor—who is single-handedly responsible for 28 percent of its total lines of code and more than 50 percent of the last two years’ commits to the project—is a current full-time Muse Group employee.

Conclusions

We can’t make absolute statements about the real intentions of Ray or Muse Group. We can only comment on their actions. That said, we’ve spent hours reviewing the company’s interactions with the open source community as well as speaking directly to Ray himself—and it seems difficult to make a case for malice, rather than simple ham-handed public relations.

Ray (for MuseScore) and Tantacrul (head of design for Audacity) each spent enormous amounts of time patiently interacting directly with the upset open source community, attempting to explain the takedown request of musescore-downloader and the proposed addition of basic telemetry in Audacity. Tantacrul himself is a well-known composer and software designer (for example, he contributed heavily to Ubuntu Touch), and Ray is clearly both enthusiastic and knowledgeable about open source software.

The worst facet of Muse Group’s attempt to take down musescore-downloader is its discussion of Xmader’s status as a Chinese expat and warnings of the possible draconian consequences for him should litigation begin. On face value, it’s easy to interpret this as a thinly veiled blackmail attempt—but given Muse Group’s repeated and lengthy attempts to engage with the community on a direct, personal level, we don’t find that likely.

It seems much more likely that Ray’s statements should be taken exactly at face value—as earnest if ham-handed concern about a bright young developer’s future, and a desire to avoid hurting him in the process of exercising Muse Group’s own necessary due diligence. Assuming that’s the case, Muse Group’s next acquisition should probably be a public relations firm instead of a software project.