OneWeb has put up another 36 satellites, taking its in-orbit constellation to 146 spacecraft.

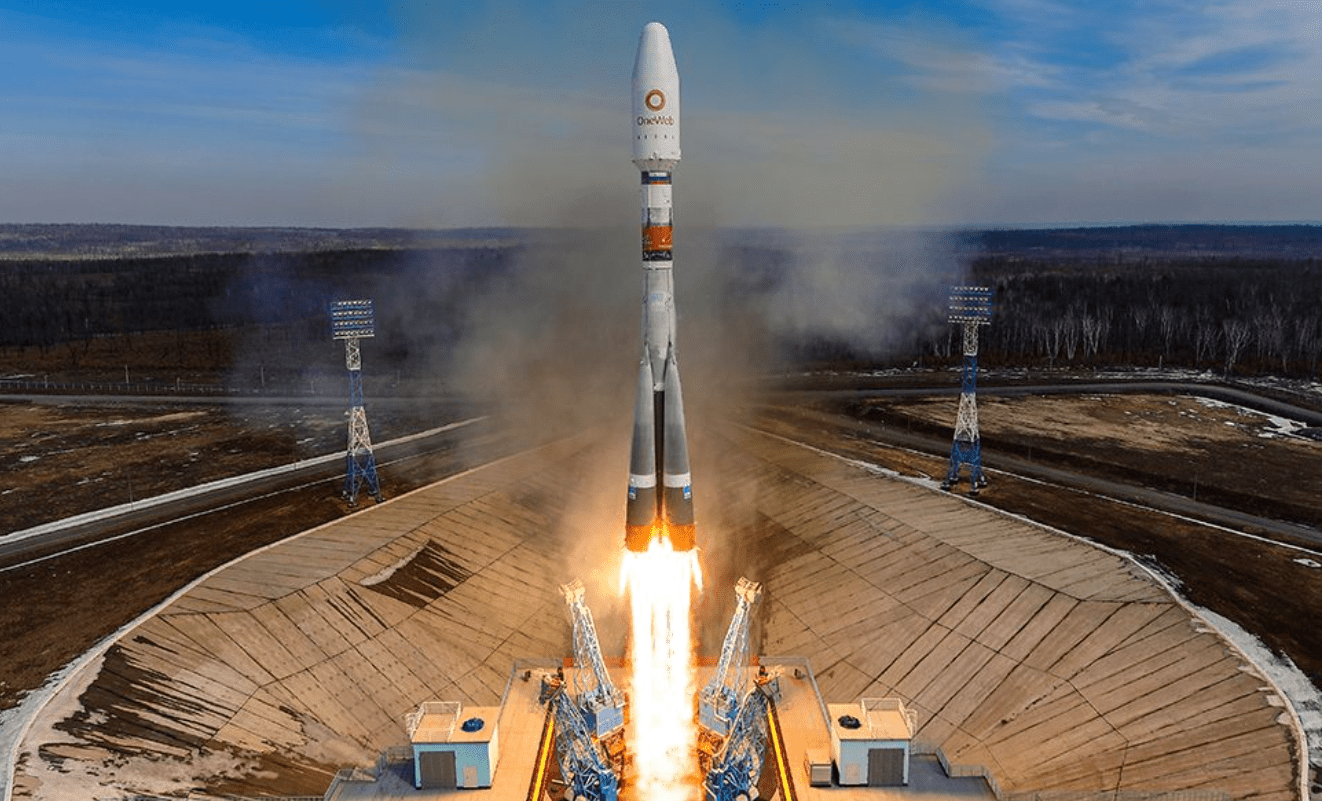

The new platforms were lofted by a Soyuz rocket from Russia’s far east.

The additions will enable engineers to further test the company’s promised system for delivering broadband internet connections from space.

OneWeb is now owned principally by the Indian conglomerate Bharti Global and the UK government after they bought the enterprise out of bankruptcy last year.

The new management anticipates offering a commercial service this autumn to northern latitudes – including Britain, Northern Europe, Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Iceland, and Arctic Seas – with a full global roll-out of connectivity in mid-2022.

“We have what we call ‘five to 50’ (degrees latitude). So, that’s five launches we need to do in order to get to this coverage of basically the south coast of the UK to the North Pole,” explained chief executive Neil Masterson.

“By the end of June we will have completed those launches to enable us to be providing our service. But in total this year, we expect to be doing somewhere between eight and 10 launches,” he told BBC News.

Mr Masterson, formerly the co-chief operating officer at business information provider Thomson Reuters, was brought into OneWeb when it emerged from “Chapter 11” bankruptcy protection in November.

There has been an intense period of hires, with more than 200 employees joining the books since the autumn.

Supply chains have also had to be re-established, allowing OneWeb Satellites, the joint venture with Airbus, to resume full-volume manufacturing at its factory in Florida.

And all this has required extra funding, of course.

OneWeb announced in January it had raised a further $400m from tech investor Softbank and satellite services specialist Hughes Network Systems. But this still leaves OneWeb short of about $1bn to finish the set-up of its first-generation constellation of 648 satellites.

Those spacecraft also need an array of supporting ground stations dotted around the globe.

“We need one more ground station to fully support commercial service in the areas mentioned by the end of this year,” the chief executive said.

“We know where it’s going to be. Covid makes it a little bit more tricky, but I think we feel confident at this stage, we’ll get it done.”

OneWeb says its testing programme is progressing well, and in a demonstration this month for the US Department of Defense claimed its satellites were providing downlink data rates of up to 500 megabits per second with a delay, or latency, in the internet connections as low as 32 milliseconds.

OneWeb’s chief competitor in the internet mega-constellation business is Starlink, which is being set up by the Californian rocket company SpaceX.

Starlink, which has 1,320 satellites in orbit now after another launch on Wednesday (the architecture of its network requires more satellites than OneWeb) has already begun beta testing with high-latitude customers.

The two projects are, though, following quite different business models.

OneWeb will be working with partner telecommunications companies to deliver its broadband offering, whereas Starlink will be selling a big chunk of its bandwidth direct to the consumer.

Some way behind both OneWeb and Starlink are Lightspeed and Kuiper.

Lightspeed is the broadband mega-constellation being developed by the long-established Canadian satellite communications company Telesat. This system has only just selected a spacecraft manufacturer in the Franco-Italian aerospace company Thales Alenia Space. The first of Lightspeed’s 298 satellites won’t launch for another two years.

Kuiper is a subsidiary of online retailer Amazon. Like Starlink, the Kuiper constellation will comprise several thousand satellites but details of a launch schedule have not been released.

There are tentative proposals in the EU also for a communications mega-constellation.

In the UK, the government’s purchase of a stake in OneWeb has been controversial, especially with an early suggestion that the constellation could be fashioned into some sort replacement for the EU’s Galileo navigation system which Britain no longer has a stake in after Brexit.

It was confirmed this week that OneWeb has answered the Request for Information now being run in government to find solutions to the country’s needs for precise Positioning, Navigation and Timing, or PNT.

But this is likely, certainly in the short term, to take the form of resilience support. In other words, using OneWeb to bolster the signals coming from Galileo and its American counterpart, GPS.

Mr Masterson says his team are thinking about the services they could offer in the future, especially when OneWeb introduces a second generation of spacecraft – the manufacture of which will have a lot more British involvement.

Carissa Christensen, the chief executive of consultancy Bryce Space and Technology, discussed OneWeb on a recent edition of the BBC’s Bottom Line business programme.

She said: “The UK has targeted space as a driver of economic growth. OneWeb is in a very exclusive club with regard to space capabilities and space activities, and so for me there’s some alignment in that decision to become an investor in OneWeb with that vision of space driving a post-Brexit UK economic boom.

“I don’t want to overstate that as saying, ‘clearly that’s going to work’. But it’s taking on an opportunity and it’s a bold decision.”