About a month into the pandemic, Tyler Mathiesen lost his position at a tech company, his first full-time job out of college. For several months, everything was fine: Payments on his $75,000 in student loans were paused, and the extra $600 weekly federal unemployment benefit helped pay the rest. He even managed to save some money.

But as the summer ended, the added benefit expired and his regular state unemployment benefits were close to running out. He needed a plan, and fast.

His solution: draining all $8,200 he had in his 401(k).

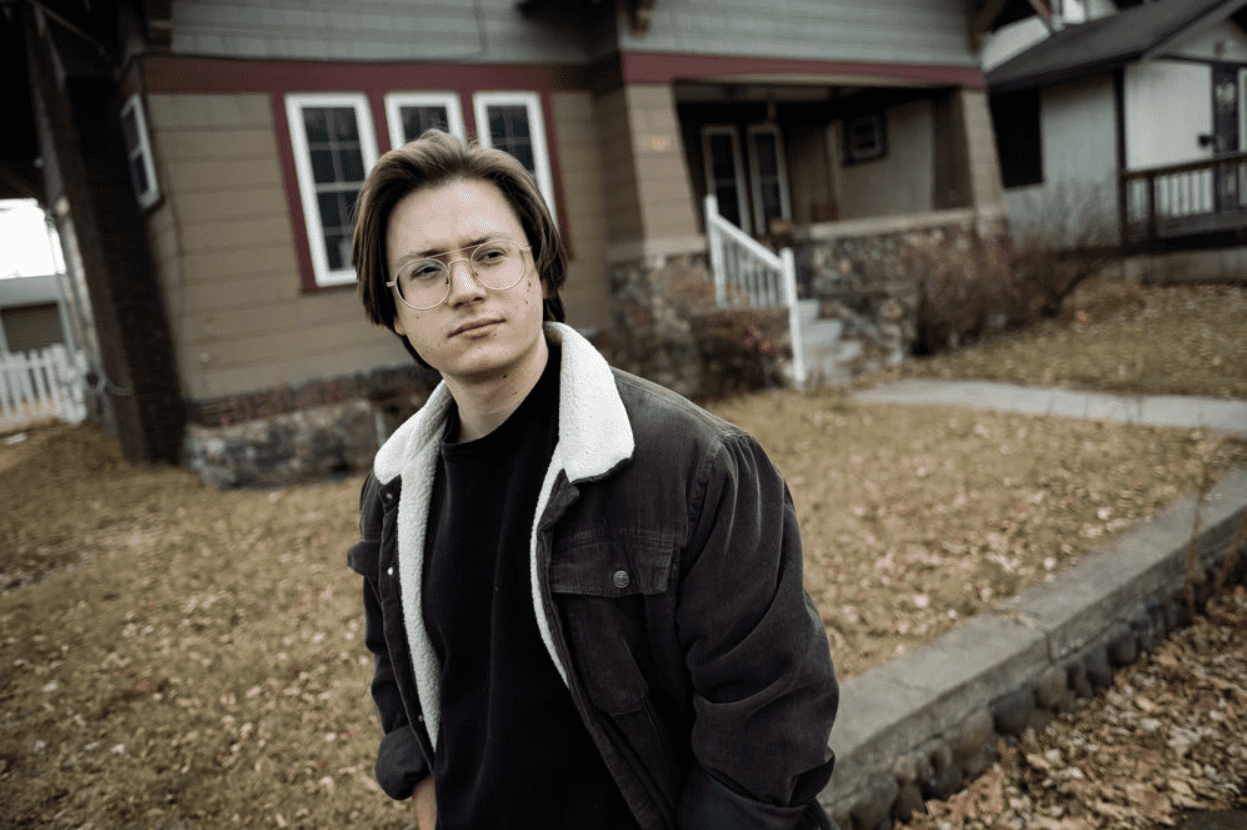

“I needed money to pay for rent and food,” said Mr. Mathiesen, 24, who lives with his girlfriend in St. Paul, Minn. With no clear indication that further relief would be on its way, he said, “I figured this was my only realistic way to get money that I needed.”

Since the pandemic began rippling through the economy in March, more than 2.1 million Americans have pulled money from retirement plans at the five largest 401(k) plan administrators — Fidelity, Empower Retirement, Vanguard, Alight Solutions and Principal. These workers, especially those in hard-hit industries like transportation, manufacturing and health care, have been helped by more flexible withdrawal rules created by the coronavirus relief legislation known as the CARES Act.

Even with millions unemployed and the economy’s recovery shaky at best, that’s only about 5 percent of the eligible 401(k) and 403(b) clients across all of those companies. But that’s still higher than in a more typical year, when many participants can still generally withdraw money for hardships, albeit under a stricter set of rules.

The various federal relief programs put into place — including stimulus payments, more generous unemployment benefits and the suspension of federal student loan payments — have helped curb the damage, retirement experts said. But some of those programs have already run out, or could soon.

“As these start to expire, there may be an uptick in withdrawals for households that have been financially impacted,” said David Fairburn, associate partner at Aon, a professional services firm that provides retirement consulting. “For example, maybe an active employee’s spouse had a job loss, so a withdrawal would be helpful to make up for the lost household income.”

Usually, pulling out money from a tax-deferred account before age 59½ would set off a 10 percent penalty on top of any income taxes. But under the temporary rules part of the CARES Act, people with pandemic-related financial troubles can withdraw up to $100,000 from any combination of their tax-deferred plans, including 401(k), 403(b), 457(b) and traditional individual retirement accounts — without penalty. The rules apply to plans only if your employer opts in, and they expire on Dec. 30.

Some plans already permitted hardship withdrawals under certain conditions, and the rules for those were loosened a bit in 2019. But the CARES Act rules are even more lenient: Virus-related hardship withdrawals are still treated as taxable income, but the liability is automatically split over three years unless the account holder chooses otherwise. And the tax can be avoided if the money is put back into a tax-deferred account within three years.

At Fidelity, the largest provider of retirement plans, roughly 1.4 million participants have taken coronavirus-related withdrawals through Nov. 21, or about 5.6 percent of eligible workplace plan participants. About 2.2 percent of participants a year took traditional hardship withdrawals in recent years, Fidelity said.

The average total withdrawal this year was about $20,000, often spread over two or three transactions. That’s more than three times as much as the typical hardship withdrawal — less than $6,000 in a 12-month period — for the last several years.

“People are taking just what they need, and they are trying to minimize the impact to their overall savings,” said Jeanne Thompson, senior vice president for workplace consulting at Fidelity. “There is a recognition that 401(k)s will be their primary source of income, and people don’t want to raid it unless they have to.”

Other large workplace 401(k) providers witnessed similar behavior. Vanguard — with five million total plan participants — said 5.3 percent of those with a coronavirus-related withdrawal option have taken one through Nov. 30, with an average amount of $23,900. Roughly 3.2 percent of eligible participants, on average, took a traditional hardship withdrawal over the last five years, with an average withdrawal of $7,351.

At Principal, about 5.7 percent of the 2.6 million participants with a coronavirus-related distribution option available have taken one through Nov. 30, with an average withdrawal of $16,500. Most of them had balances of less than $25,000, and workers in the manufacturing, health care and professional/scientific industries made the highest number of requests, the company said.

(Individual retirement accounts may also be tapped, but experts said detailed withdrawal data won’t be available until after those people file tax returns.)

There’s a good reason many people haven’t taken withdrawals: Those most in need of cash right now don’t have the luxury of an account to raid.

Only about half of households have balances inside 401(k) plans or individual retirement accounts, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. And lower-paid workers without retirement plans have suffered a disproportionate share of the pandemic-related job losses, experts said.

The dynamics have brought into even clearer focus how few households have emergency savings accounts — and it has prompted more employers to start their own programs. For now, about 10 percent of large employers offer some type of support to encourage rainy day savings, according to Aon, whether it’s providing a way to set aside money inside a retirement plan or simply education.

But the scope of the damage wrought by the pandemic means that even the traditional emergency savings advice — putting aside roughly three to six months of basic living expenses — hasn’t necessarily been enough to provide a cushion. Someone who lost a job in March could have easily burned through that amount of savings.

Even though pandemic-related withdrawals come with fewer penalties, they’re still a blow to a person’s retirement savings. How aggressively they must save to make up the difference will depend on their time horizon, earnings and how much they’ve pulled out.

Consider a 43-year-old earning $62,000 who withdrew about $10,400 — the typical participant who had taken a withdrawal through May, according to an analysis by Vanguard. That missing $10,000 would have grown to about $25,000 over the next 24 years, assuming an investment return of 4 percent after inflation. To close the shortfall, people in that situation would have to increase their savings rates one percentage point a year.

But those who had to take a withdrawal may not be in a position to dial up their savings for some time, and the longer they have to wait to start saving again, the more aggressive they have to be.

Younger people, like Mr. Mathiesen, have more time to make up ground. Even so, he is worried about how long it will take to get back to work, preferably in his field of study — audio engineering and sound design.

Although he has had a couple of leads, Mr. Mathiesen is trying to find a job where he can work from home indefinitely. He said his partner has a rare autoimmune disease, which would put her more at risk if she were to contract the coronavirus.

And other uncertainty abounds: Mr. Mathiesen doesn’t know if negotiations in Washington will bring back more lucrative or extended unemployment benefits, and his student loan bills will have to be paid again starting in February if the moratorium on those payments isn’t extended further.

“I’m young enough where I can reset and that wouldn’t put me too far behind,” he said. “But I also don’t even know when I’ll be able to start making progress again.”