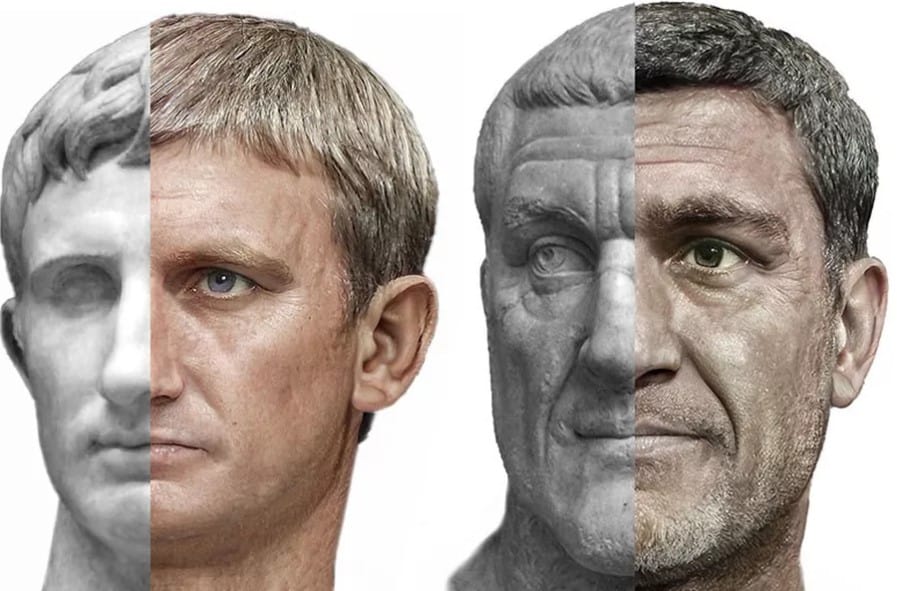

Machine learning is a fantastic tool for renovating old photos and videos. So much so that it can even bring ancient statues to life, transforming the chipped stone busts of long-dead Roman emperors into photorealistic faces you could imagine walking past on the street.

The portraits are the creation of designer Daniel Voshart, who describes the series as a quarantine project that got a bit out of hand. Primarily a VR specialist in the film industry, Voshart’s work projects got put on hold because of COVID-19, and so he started exploring a hobby of his: colorizing old statues. Looking for suitable material to transform, he began working his way through Roman emperors. He finished his initial depictions of the first 54 emperors in July, but this week, he released updated portraits and new posters for sale.

Voshart told The Verge that he’d originally made 300 posters in his first batch, hoping they’d sell in a year. Instead, they were gone in three weeks, and his work has spread far and wide since. “I knew Roman history was popular and there was a built-in audience,” says Voshart. “But it was still a bit of a surprise to see it get picked up in the way that it did.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21805552/1__7_8D7pwyK0T_mvczazJIA.jpeg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21805553/1_zEHyWWC0cSzXuSDaaiUiKQ.jpeg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21805554/1_oeT1kwYwi0BJjkDuIjGxwg.jpeg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21805555/1_SX47ZQ5dn20QzrQdKUAOcQ.jpeg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21805556/1_830pKWK3Upb1MzEZe8MPrA.jpeg)

To create his portraits, Voshart uses a combination of different software and sources. The main tool is an online program named ArtBreeder, which uses a machine learning method known as a generative adversarial network (or GAN) to manipulate portraits and landscapes. If you browse the ArtBreeder site, you can see a range of faces in different styles, each of which can be adjusted using sliders like a video game character creation screen.

Voshart fed ArtBreeder images of emperors he collected from statues, coins, and paintings, and then tweaked the portraits manually based on historical descriptions, feeding them back to the GAN. “I would do work in Photoshop, load it into ArtBreeder, tweak it, bring it back into Photoshop, then rework it,” he says. “That resulted in the best photorealistic quality, and avoided falling down the path into the uncanny valley.”

Voshart says his aim wasn’t to simply copy the statues in flesh but to create portraits that looked convincing in their own right, each of which takes a day to design. “What I’m doing is an artistic interpretation of an artistic interpretation,” he says.

To help, he says he sometimes fed high-res images of celebrities into the GAN to heighten the realism. There’s a touch of Daniel Craig in his Augustus, for example, while to create the portrait of Maximinus Thrax he fed in images of the wrestler André the Giant. The reason for this, Voshart explains, is that Thrax is thought to have had a pituitary gland disorder in his youth, giving him a lantern jaw and mountainous frame. André the Giant (real name André René Roussimoff) was diagnosed with the same disorder, so Voshart wanted to borrow the wrestler’s features to thicken Thrax’s jaw and brow. The process, as he describes it, is almost alchemical, relying on a careful mix of inputs to create the finished product.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21805550/1_N0gjkIOYEdrHUviORQeGVg.jpeg)

Perhaps surprisingly, though, Voshart says he wasn’t really that interested in Roman history prior to starting this project. Digging into the lives of the emperors in order to create his portraits has changed his mind, however. He’d previously dismissed the idea of visiting Rome because he thought it was a “tourist trap,” but now says “there are specific museums I want to hit up.”

What’s more, his work is already enticing academics, who have praised the portraits for giving the emperors new depth and realism. Voshart says he chats with a group of history professors and PhDs who’ve given him guidance on certain figures. Selecting skin tone is one area where there’s lots of dispute, he says, particularly with emperors like Septimius Severus, who’s thought to have had Phoenician or perhaps Berber ancestors.

Voshart notes that, in the case of Severus, he’s the only Roman emperor for whom we have a surviving contemporary painting, the Severan Tondo, which he says influenced the darker skin tones he used in his depiction. “The painting is like, I mean it depends on who you ask, but I see a dark skinned North African person,” says Voshart. “I’m very introducing my own sort of biases of faces I’ve known or have met. But that’s what I read into it.”

As a sort of thank you to his advisers, Voshart has even used a picture of one USC assistant professor who looks quite a bit like the emperor Numerian to create the ancient ruler’s portrait. And who knows, perhaps this rendition of Numerian will be one that survives down the years. It’ll be yet another artistic depiction for future historians to argue about.

You can read more about Voshart’s work here, as well as order prints of the emperors.