How are we to characterize this stock-market struggle of the past three months and beyond?

By the most simplistic definition, it became a bear market when the S&P 500 dropped more than 20% from its high, which it did on the way to a fast 35% decline over five weeks. And will remain a bear market unless and until the index recovers to the February high. After another winning week, the benchmark is 15% from that record.

But that classification of a bear market encompasses everything from the 1987 crash and the quick 1962 tumble that became a mere footnote in the post-1950 advance, to the grinding multi-year ordeals of the 1970s and early 2000s.

Ned Davis Research has its own checklist to identify a bear market, including either a 30% drop in the Dow Jones Industrials after 50 days or at least a 13% decline that lasts over 145 days. The latter definition tags the 2015-early 2016 downturn as a bear, while most investors viewed it as a steep correction that refreshed the bull market.

Another way to capture the experience of an underwater market and quantify the wear and tear it takes on public psychology and portfolio values is how long the market stays at more than a 10% deficit to its peak level.

I asked Ryan Detrick, market strategist at LPL Financial, to chart past market downturns by how many days the S&P 500 remained down 10% or more. Since the market first broke to an all-time high after the global financial crisis in 2013, the current 55 days in a 10% “drawdown” is by far the longest, more than twice the duration of the late-2018/early 2019 setback.

Yet widening the view back to 1980, the present streak is barely visible, less than half as long as anything we now describe as a bear market, such as the 1990 decline associated with a fairly shallow recession.

Of course, this market could stall or slide from here and remain mired under the 10%-loss threshold for a long time. Yet it would only take less than a 4% advance from here for the S&P to narrow its deficit against the peak to less than 10% and end this streak.

Investors say this is a bear market rally

This all is largely a matter of semantics, a bar stool debate topic. But how an investor defines this episode probably dictates what he or she expects it do to from here, and how much exposure to equities seems to make sense now, after the S&P 500 has recouped more than 60% of its loss.

And, indeed, at least until recently, most professional investors seem to be working from a premise that this is a bear market. Nearly 70% of the participants in Bank of America’s monthly global fund manager survey (which captured responses from May 7-14) called the recent rebound a bear market rally – something BofA strategists argue shows sentiment to be crowded on the cautious side, a net positive for a bit further upside for stocks.

Stephen Suttmeier, technician at BofA, knits together the contrasting views of this phase by pointing to previous long-running – or “secular” bull markets beginning at a “generational low” which had a severe retrenchment in their seventh year, including 1957 and 1987.

By some measures, the market is stretching the bounds of a bear-market bounce.

Chris Verrone, technical strategist at Strategas Research, points out that the S&P 500′s 40-day surge of nearly 31% is second only to the ramp off the final March 2009 bottom in terms of upside over the same time span. And the other dates of comparable rallies mostly coincide with important, decisive lows in such years as 1982, 1998, 1975 and early 2019.

A notable exception: the strong post-9/11 bounce in the fall of 2001, which gave way to a resumption of a nasty bear market that brought new lows nearly a year later.

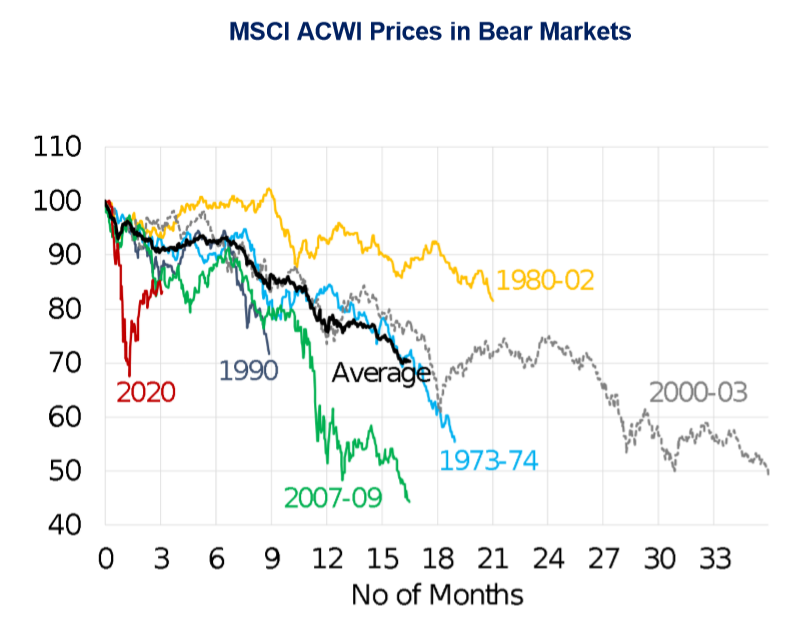

Citigroup tracks the global equity market since the recent peak against the path of other confirmed bear markets, which makes it appear the current rally is overachieving for now – but perhaps only because the collapse was so fast and deep.

Beyond the straight magnitude of the decline and degree of recovery, the 2020 market top differs in character with a typical bear market. For sure, this one is associated with a recession, as most bears are, but an engineered one that began from a fairly healthy economic condition.

Not a typical bear

More familiarly, a bull market will weaken and falter in phases, at first in a subtle way below the surface, as a business expansion peters out and/or central banks tighten too much.

This was a guillotine slice of more than $10 trillion in market cap from an all-time peak brought about by a pandemic and public-policy responses to it. A rare, if not unprecedented, situation.

Bear markets also typically act as a crucible for a tide change in market leadership. In the 2000-2002 bear, led lower by tech and other growth stocks, small-caps and value stocks began to outperform and powered the subsequent upturn.

Financials and energy were tops heading into the 2007-2009 collapse and lagged badly versus tech and consumer stocks in the post-’09 advance.

So far, the mega-cap growth and tech leadership that prevailed in the run up to the February peak have continued to outperform since. There have been only the most halting, marginal signs so far that more cyclical value and financial stocks might close the vast performance gap.

And yes, far more is unique to this moment: the immediate depth of the economic shock, the wide range of possible disease paths (good and bad) and the enormous rapid central-bank and fiscal support sending trillions of dollars into the economy in a rush.

So, no matter what we call it, this market has both earned some respect for its resilience and has plenty more to prove given the uneven terrain ahead and distance back to what most investors would consider a normal economy.