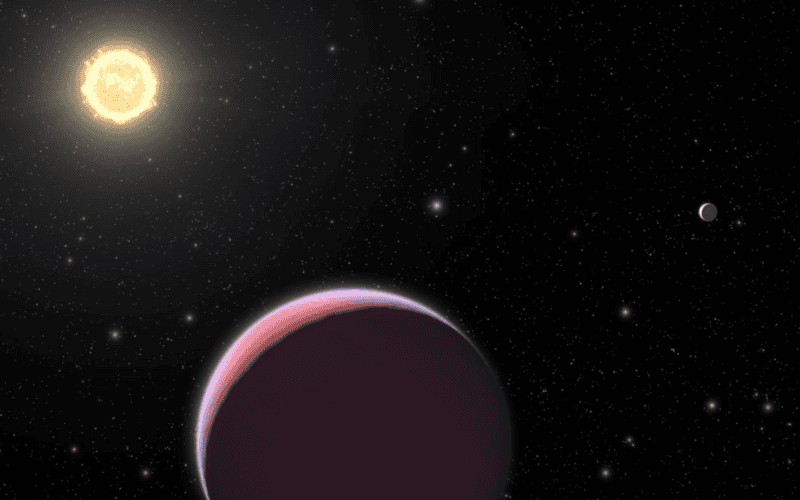

Kepler-51 is a 500-million-year-old G-type star located 2,615 light-years away in the constellation of Cygnus. New observations from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope have revealed that Kepler-51 is host to three of the lowest density exoplanets known to date. With densities less than 0.1 g/cm3, these planets have atmospheric scale heights 10 times larger than a typical hot-Jupiter exoplanet.

Super-puffs are extrasolar planets with masses only a few times larger than Earth’s, radii larger than Neptune, and very low densities.

First discovered by NASA’s Kepler space telescope, these planets are relatively rare in our Milky Way Galaxy — fewer than 15 have been discovered so far.

“Kepler-51’s trio take planetary puffiness to new levels,” said Dr. Zachory Berta-Thompson, an astronomer in the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

“Their discovery was straight-up contrary to what we teach in undergraduate classrooms.”

Also known as KOI-620, Kepler-51 hosts three Jupiter-sized planets — Kepler-51b, c and d — with orbital periods of 45, 85 and 130 days.

Discovered by Kepler in 2012, these planets are several times the mass of Earth, and have hydrogen/helium atmospheres.

“All three planets had a density less than 0.1 g/cm3 of volume — almost identical to the sweet pink treats you can buy at any fairground,” said Jessica Libby-Roberts, a graduate student in the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences) at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

“We knew they were low density. But when you picture a Jupiter-sized ball of cotton candy — that’s really low density.”

Dr. Berta-Thompson, Libby-Roberts and their colleagues observed two transits of Kepler-51b and d with Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3.

The researchers found the spectra of both planets not to have any telltale chemical signatures.

“This was completely unexpected. We had planned on observing large water absorption features, but they just weren’t there. We were clouded out,” Libby-Roberts said.

“However, unlike Earth’s water-clouds, the clouds on these planets may be composed of salt crystals or photochemical hazes, like those found on Saturn’s largest moon, Titan.”

These clouds provide the scientists with insight into how Kepler-51b and d stack up against other low-mass, gas-rich exoplanets.

“When comparing the flat spectra of the super-puffs against the spectra of other planets, we were able to support the hypothesis that cloud/haze formation is linked to the temperature of a planet — the cooler a planet is, the cloudier it becomes,” they said.

“The low densities of these planets are in part a consequence of the young age of the system, a mere 500 million years old, compared to our 4.6-billion-year-old Sun.”

“Models suggest these planets formed outside of the star’s ‘snow line,’ the region of possible orbits where icy materials can survive. The planets then migrated inward.”

The authors also found that Kepler-51b, c and d are shedding gas at a rapid pace.

They calculated that if that trend continued, the planets could shrink considerably over the next billion years, losing their puffiness. In the end, they might wind up looking more like a common class of exoplanets called ‘mini-Neptunes.’

“People have been really struggling to find out why this system looks so different than every other system. We’re trying to show that, actually, it does look like some of these other systems,” Libby-Roberts said.

“A good bit of their weirdness is coming from the fact that we’re seeing them at a time in their development where we’ve rarely gotten the chance to observe planets,” Dr. Berta-Thompson added.

The team’s paper will be published in the Astronomical Journal.