Computer scientists and humanities scholars have been trying for more than decade to produce software that can accurately read Arabic text and transform it into a digital format, a task that has thus far eluded them. But artificial intelligence is changing that, opening up the possibility of getting archives of newspapers, magazines, and books available to all on the Internet.

“For a long time, accurate and reliable Arabic optical character recognition has remained sort of a mirage for academics (especially in the humanities) and librarians. Advances in the field in recent years have however gradually been transforming it into a reality,” writes Dominique Akhoun-Schwarb, curator of rare books and manuscripts at SOAS, University of London, in an e-mail.

Arabic text is harder for computers to read than the Latin alphabet. Arabic and its related languages Persian, Ottoman Turkish and Urdu are written as a continuous script; consonant letters have a variety of shapes depending on their place in a word and there are markings below and above letters that are essential to a word’s meaning but can be hard to see.

Despite these challenges, Akram Khater, director of the Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies at North Carolina State University in the United States, says it’s an endeavor worth pursuing.

To be able to accurately digitize Arabic printed text, Khater says, “will open up millions of pages of data that are currently inaccessible. It will facilitate research not only by scholars, but by the general public, and that’s why we need it.”

Software to digitize the Arabic language does already exist, but Khater says it is “limited and frustrating” to use. The development of optical character recognition software that can digitize Arabic text has lagged behind comparable software for European languages.

Developments in what is known as “machine learning” have resulted in a number of open-source projects that represent a step forward in the quality of systems that can read and digitize Arabic text, potentially offering a wealth of new opportunities for scholars and general readers.

New Access to Old Newspapers

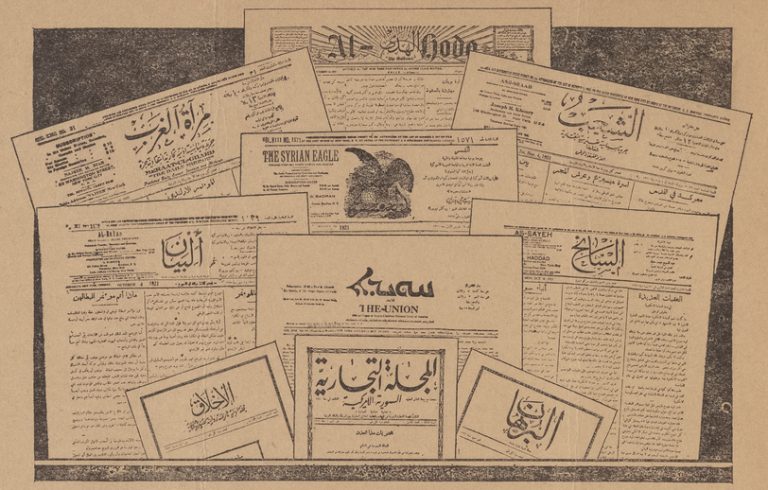

As part of its work documenting the experience of Lebanese immigrants in the United States and elsewhere, the Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies has collected Arabic-language newspapers published in the United States from the 19th century onwards. These newspapers are a rich source of social history, but were so laborious to study (blurry text on cheap paper, with no index) that they were almost inaccessible.

Khater responded to the problem by engaging members of his university’s information technology department to devise an optical character recognition program that could read the text of old Arabic-language newspapers and convert the text into digital form. A single name can now be found by typing it into a search box, rather than leafing through page after page in the hope of finding it.

The system took about a year and a half to develop, Khater said, and it was tailored to the needs of the Khayrallah Center, adapting an open-source software called Tesseract. Speaking at a conference in the United Kingdom in April, Khater said the bespoke software had achieved an accuracy rate of 98 percent in converting the Arabic-language newsprint into digital text.

The Khayrallah Center’s software is far from being a consumer product. “You can’t just download a user-friendly version,” Khater said. “It’s not intuitive, with drop-down menus. To use it as it is now, you have to be able to write code.” The team is working on a web-based search function that will be easy to use, however, and they hope to share the application as widely as possible.

Digitizing Historical Printed Texts

Separately and in parallel with the North Carolina State effort, a multi-institutional project called the Open Islamicate Texts Initiative, known as OpenITI, has been developing a comparable Arabic optical character recognition application, based on an open-source platform called Kraken. Like the Tesseract-based application, the OpenITI version uses advanced machine learning to analyze entire lines of text, rather than single characters.

These new Arabic optical character recognition systems are capable of learning from text as they read it, leading to what developer David Smith, an associate professor at Northeastern University’s College of Computer and Information Science, calls a “virtuous cycle,” in which the more text the system reads, the more it learns and the greater its accuracy.

OpenITI has received funding to develop user-friendly, open-source software capable of creating digital texts from Persian and Arabic books. Its software is already in use by the Kitab Project, which applies quantitative analysis to medieval Islamic texts. Digitized texts can be searched in ways that no human scholar could, opening up new prospects for the study of Islamic texts. For example, Sarah Bowen Savant, a professor at Aga Khan University and a co-principal investigator on the Kitab Project, has used quantitative analysis to trace how medieval Muslim authors re-used pre-existing material to create voluminous encyclopedic works, such as the chronicles of the Abbasid historian al-Tabari.

OpenITI is focusing on printed books, not hand-written manuscripts. Printed books are easier to digitize than manuscripts, but the printed books in existence since the introduction of printing into Arab and Islamic countries “include works from over a thousand years of cultural production,” said Matthew T. Miller, assistant professor of Persian literature and digital humanities at the University of Maryland in the United States.

Digitizing manuscripts is the obvious next step for this technology, Akram Khater said, though it represents a further step in complexity, due to the challenges of different styles of hand-written script used in historic manuscripts, the colors of ink used, and the presence of marginalia and commentary.

These open-source Arabic optical character recognition projects demonstrate that developing this kind of tool is an enterprise with a low barrier to entry. The basic software is free, and anyone with the time and the skill can create their own tailor-made Arabic character recognition software.

With these new software tools, ancient texts can be read, searched and studied by scholars around the world.