Picture a world where rain falls, gathers in lakes and ponds, seeps into the surrounding rock, and evaporates away, only to fall again. There’s just one catch: The world is Saturn’s moon, Titan, where the rain isn’t water; it’s liquid methane.

Two new papers explore how this eerily familiar, waterless “water cycle” manifests on Titan’s surface. To do so, two separate research teams turned to data from the Cassini mission, which ended its stay at the Saturn system in September 2017. The spacecraft flew past the massive moon more than 100 times, gathering crucial observations of this strange world as it did so.

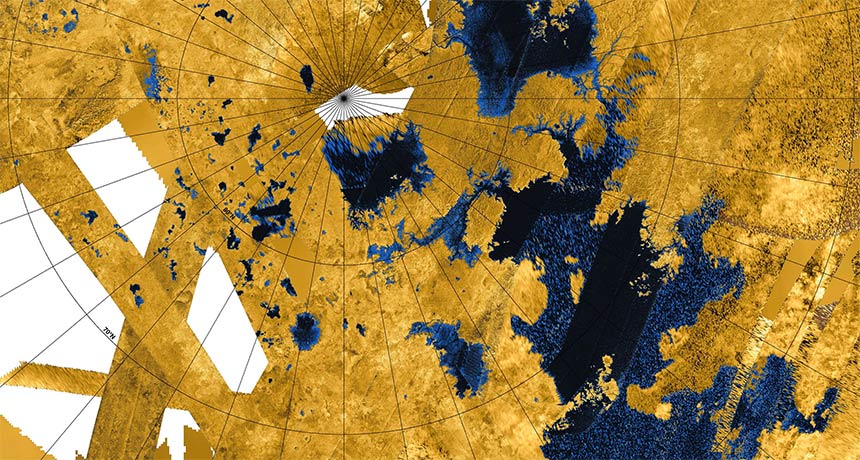

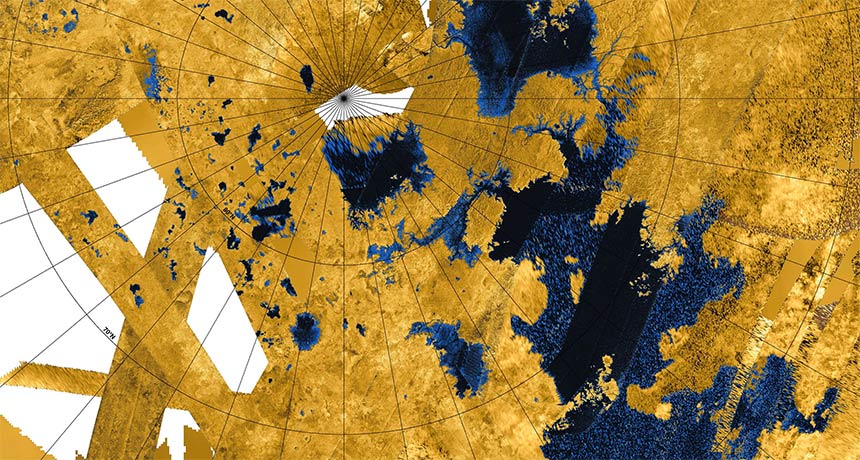

Some of those observations showed scientists something truly extraordinary: their first glimpse of liquid currently on the landscape, rather than mere ghosts of such liquid features. “Titan is the only world outside the Earth where we see bodies of liquid on the surface,” Rosaly Lopes, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who worked on the Cassini mission but wasn’t involved in either of the new papers. “Some of us like to call Titan the Earth of the outer solar system.”

“Titan is the most interesting moon in the solar system. I think that gets me some enemies, but I think it’s actually true,” Shannon MacKenzie, lead author on one of the new studies and a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory, told Space.com. But that doesn’t mean the moon is straightforward. “Titan throws us a lot of curveballs,” she said.

MacKenzie’s study analyzes one potential curveball: three small features that appeared to be liquid-filled lakes when Cassini first spotted them, but seem to have dried up by the time the spacecraft returned to the area. The observations suggest that the liquid either evaporated or seeped into the surrounding planetary surface.

These “phantom lakes” may be evidence of seasonal changes on the moon, MacKenzie and her coauthors believe. (Seven Earth years passed between the spacecraft’s two observations of the area, during which the northern hemisphere of the moon transitioned from winter to spring.)

But the situation may not be quite that simple, since the two sets of observations were taken by different instruments. Cassini was built to gather data with either its radar instrument or its visual and infrared light cameras, but not both simultaneously. And during the spacecraft’s first pass, the region was too dark to use the cameras.

So MacKenzie and her colleagues had to factor in the change in instruments as a potential variable. But she’s still confident that something is different in the two passes, and that it’s pretty plausible that liquid was there, then disappeared. Even if the different signals over the two flybys were caused by some other phenomenon, MacKenzie said she’s still intrigued by what that could tell us about the strange moon, which is among scientists’ plausible candidates for where life may be lurking beyond Earth.

“If we’re instead looking at some newly identified materials on the surface, then that’s interesting, too, because the sediments on Titan are really important for prebiotic chemistry,” MacKenzie said.

But although MacKenzie focused on just three small lakes that seem to have disappeared, plenty of lakes remained visible throughout Cassini’s observations of the region. In the second paper published today, scientists used radar data to study a handful of much larger lakes.

During Cassini’s very last pass over Titan in April 2017, the spacecraft was programmed to gather a very specific type of data, called altimetry, over the lake region to measure the height of different substances. Marco Mastrogiuseppe, a planetary scientist at Caltech, had already used similar data to measure the depths of some of Titan’s seas, much larger bodies of liquids, and the Cassini team hoped he would be able to do the same with lakes.

Mastrogiuseppe and his colleagues did so in their new paper, identifying the bottoms of lakes more than 328 feet (100 meters) deep and establishing that their contents were dominated by liquid methane. “We realized that essentially the composition of the lakes is very, very similar to the one of the mare, of the sea,” he said. “We believe that these bodies are fed by local rains and then these basins, they drain liquid.”

That suggests that below Titan’s surface, the moon may host yet another feature reminiscent of Earth: caves. On Earth, many caves are formed by water dissolving away surrounding rock types like limestone, leaving behind a type of landscape called karst, characterized by springs, aquifers, caves and sinkholes.

Researchers studying Titan’s lake region think that they see similar karst-type characteristics. They also haven’t spotted channels connecting all these different liquid features, which is why Mastrogiuseppe and others suspect that some of the liquid may be seeping into the surrounding terrain, much like karst systems here on Earth.

“Titan is really this world that geologically is similar to the Earth, and studying the interactions between the liquid bodies and the geology is something that we haven’t really been able to do before,” Lopes said. The new studies begin to make that happen by seeing those interactions playing out live on another planetary body.

Of course, it’s much more difficult to study these interactions so far away, on a world that has never been the primary focus of a mission. “We’ve been talking about possible missions with robotic explorers that might crawl down into lava tubes and caves on the moon and Mars,” Lopes said. “Could we in the future send one of these to sort of crawl down into this terrain and into caves and find out what’s underneath there?”

Such a mission likely won’t happen any time soon, but NASA is seriously considering a project called Dragonfly that would land a drone on the strange moon. If selected, the mission would launch in 2025 and reach Titan nine years later. And if NASA doesn’t choose Dragonfly, chances are good that another mission concept will come along. “Titan’s just to cool to not go back to,” MacKenzie said.

Both MacKenzie’s and Mastrogiuseppe’s papers were published today (April 15) in the journal Nature Astronomy.