A gigantic solar storm hit Earth about 2,600 years ago, one about 10 times stronger than any solar storm recorded in the modern day, a new study finds.

These findings suggest that such explosions recur regularly in Earth’s history, and could wreak havoc if they were to hit now, given how dependent the world has become on electricity.

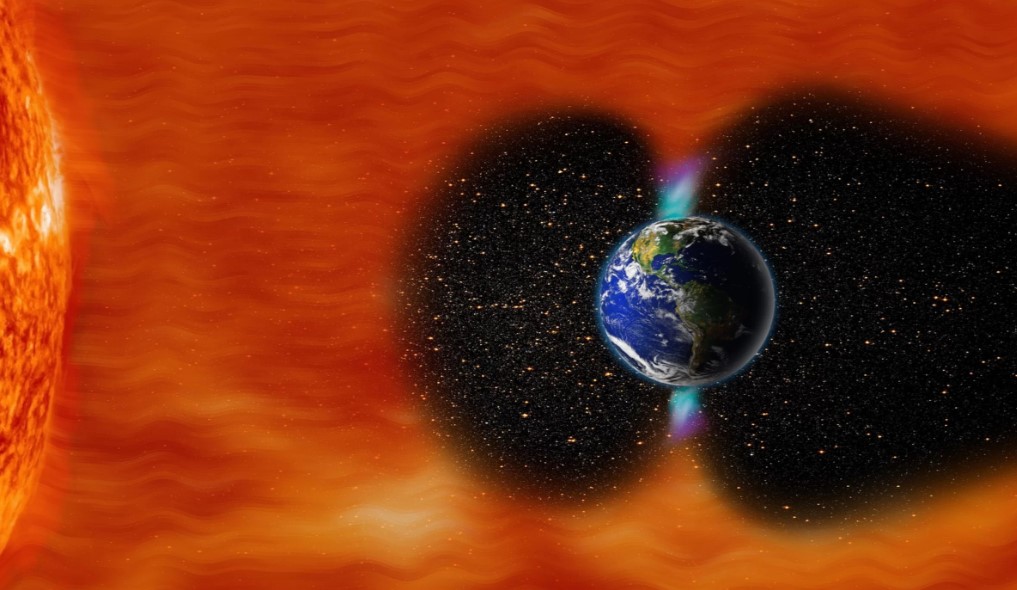

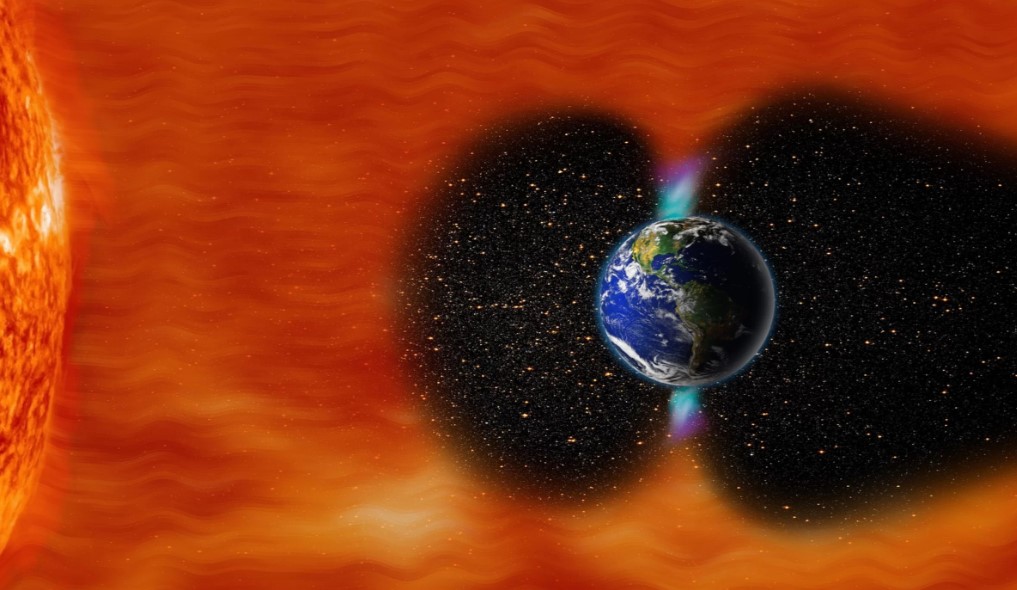

The sun can bombard Earth with explosions of highly energetic particles known as solar proton events. These “proton storms” can endanger people and electronics both in space and in the air.

In addition, when a proton storm hits Earth’s magnetosphere — the shell of electrically charged particles — it is trapped by Earth’s magnetic field. When the solar storm causes a disturbance in our planet’s magnetosphere, it’s called a geomagnetic storm which can wreak devastation on power grids across the planet. For example, in 1989, a solar outburst blacked out the entire Canadian province of Quebec within seconds, damaging transformers as far away as New Jersey, and nearly shutting down U.S. power grids from the mid-Atlantic through the Pacific Northwest.

Scientists have analyzed proton storms for less than a century. As such, they may not have good estimates of how often extreme solar eruptions happen or how powerful they can actually get.

“Today, we have a lot of infrastructure that could be badly damaged, and we travel in air and space where we are much more exposed to high-energy radiation,” senior study author Raimund Muscheler an environmental physicist at Lund University in Sweden, told Live Science.

The so-called Carrington Event of 1859 may have released about 10 times more energy than the one behind the Quebec blackout in 1989, making it the most powerful known geomagnetic storm , according to a 2013 study from Lloyd’s of London. Worse yet, the world has become far more dependent on electricity since the Carrington Event, and if a similarly powerful geomagnetic storm were to hit now, power outages might last weeks, months or even years as utilities struggle to replace key parts of power grids, the 2013 study found.

Now, researchers have found radioactive atoms trapped within ice in Greenland that suggest an enormous proton storm struck Earth in about 660 B.C., one that might dwarf the Carrington Event.

Previous research found that extreme proton storms can generate radioactive atoms of beryllium-10, chlorine-36 and carbon-14 in the atmosphere. Evidence of such events is detectable in tree rings and ice cores, potentially giving scientists a way to investigate ancient solar activity.

The scientists examined ice from two core samples taken from Greenland. They noted a spike of radioactive beryllium-10 and chlorine-36 about 2,610 years ago. This matches prior work examining tree rings that suggested a spike of carbon-14 about the same time.

Previous research detected two other ancient proton storms in a similar manner — one happened about A.D. 993-994, and the other about A.D. 774-775. The latter is the largest solar eruption known to date.

Regarding number of high-energy protons, the 660 B.C. and the A.D. 774-775 events are about 10 times larger than the strongest proton storm seen in the modern day, which occurred in 1956, Muscheler said. The A.D. 993-994 event was smaller than the other two ancient storms by about a factor of two to three, he added.

It remains unclear how these ancient proton storms compared with the Carrington Event, since estimates of the number of protons from the Carrington Event are very uncertain, Muscheler said. However, if these ancient solar outbursts “were connected with a geomagnetic storm, I would assume that they would exceed the worst-case scenarios that are often based on Carrington-type events,” he noted.

Although more research is needed to see how much damage such eruptions might inflict, this work suggests “these enormous events are a recurring feature of the sun — we now have three big events during the past 3,000 years,” Muscheler said. “There might be more that we have not yet discovered.”

“We need to search systematically for these events in the environmental archives to get a good idea about the statistics — that is, the risks — for such events and also smaller events,” Muscheler added. “The challenge will be to find the smaller ones that probably still exceed anything we measured in recent decades.”

The scientists detailed their findings online today (March 11) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.