NASA on Thursday (Aug. 30) announced a deadline for its recovery of the Mars rover Opportunity, which has been silent for months while battling a dust storm, and some scientists intimately familiar with the project say that new timeline doesn’t do the grizzled robot justice.

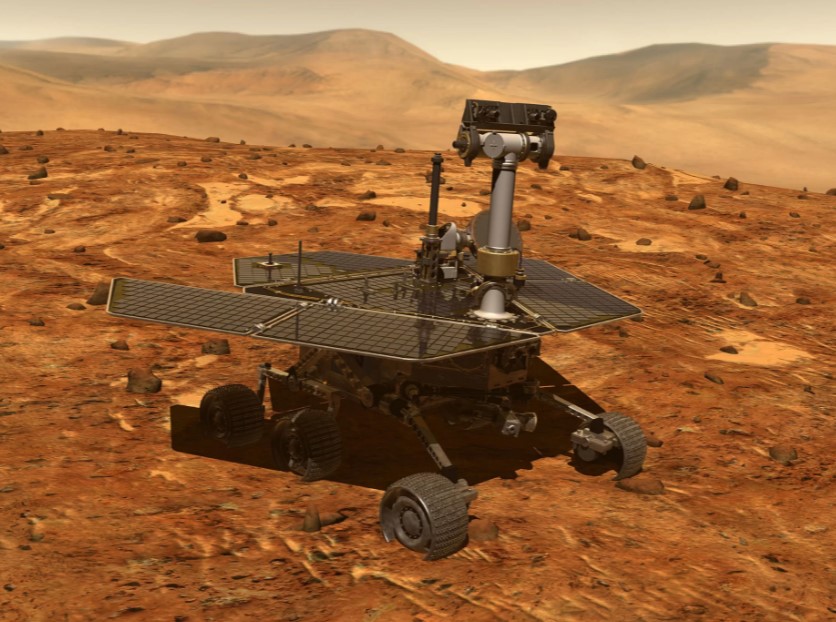

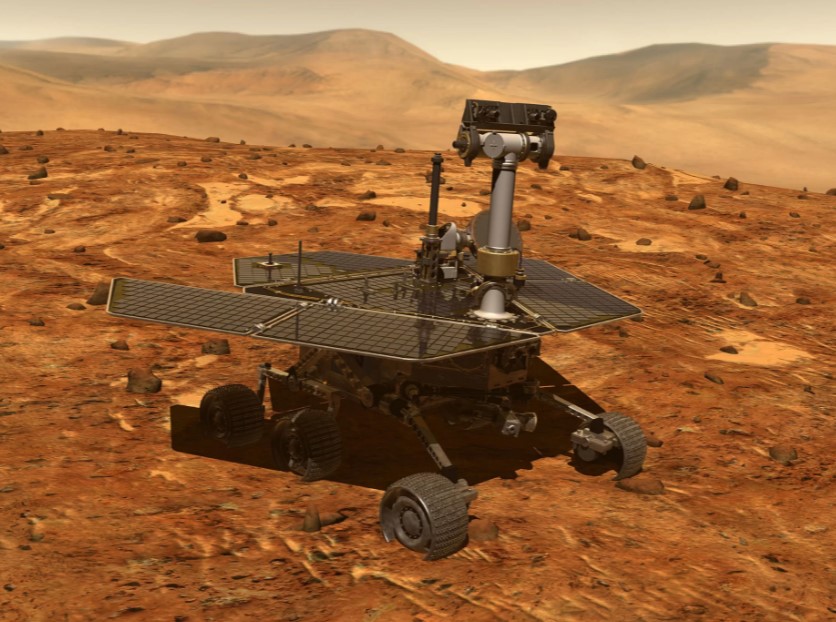

The rover, which launched in 2003 and landed on Mars in January 2004, has been giving its humans the cold shoulder since June 10, when a fierce dust storm enveloped the Red Planet and blocked the sun from the robot’s solar panels. The storm has started to die down, so the team hopes that with enough time, the rover should be able to power on again and get back to work after its long hibernation.

But scientists familiar with the mission say that NASA’s new schedule doesn’t offer the hardworking rover that time. “Opportunity has everything going for her,” Tanya Harrison, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University and a science team collaborator on Opportunity, told Space.com. She said that depending on how the timeline aligns with Martian weather, “We’re not giving it a fair shot.”

Here’s NASA’s plan: First, the team will wait until the tau — a measurement of how much dust clouds the air — lowers to 1.5. (At the peak of the storm, the tau was likely around 10, a level one rover expert called “terrifying.”) Then, the team will begin a 45-day active-listening period, during which they will send commands up to the rover that should force it to respond.

Finally, if the silence continues, the team will transition into passive listening, eavesdropping on Mars-observing antennas for chance signals from Opportunity. Regardless of when that 45-day period ends, the team will continue passively listening through the end of January, John Callas, Opportunity project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told Space.com. (NASA’s original release about the decision said simply that the team would be given “several months” for passive listening after the period of active listening ends.)

But at the end of January, the rover’s time will be up, and with it, the Mars Exploration Rovers mission, which originally consisted of Opportunity and its sister robot, Spirit. “We’re not ending the mission after 45 days,” Callas told Space.com. “But I’m not going to keep full staffing around for six months or eight months if the chance of success is low.”

Dust in the wind

If this year’s dust storm is indeed the end of Opportunity, no one will be able to say the rover wasn’t a survivor. Opportunity and Spirit, which landed on the planet in 2004, were expected to last only 90 Martian days (each about 40 minutes longer than an Earth day), on the planet’s surface — in part because scientists expected that dust would slowly bury the robots, according to Don Banfield, a planetary scientist at Cornell University who works with the Mars Exploration Rover team. But Spirit lasted for seven years, and Opportunity was approaching its 15th year at work when the storm hit. [Mars Dust Storm 2018:What It Means for the Opportunity Rover]

Banfield said that this storm is serious business, one of the biggest observed from the Martian surface to date. Although the storm is clearing, it’s difficult for scientists to predict how tau, their crucial measure of light penetrating to the surface, will fare. “Getting that last little bit of dust out of the air takes a good amount of time,” Mike Seibert, a former flight director for the Mars Exploration Rovers program, told Space.com.

There’s also one big problem with the Martian skies clearing: All that dust has nowhere to go but down. “I think that’s the real scary thing right now is that we know that the dust is going to fall out of the sky, but it has to go somewhere,” Banfield said. Dust sitting on Opportunity’s solar panels will block the rover’s power supply just as effectively as dust in the air does, and, according to Seibert, engineers have no way to figure out how dusty the panels are.

One factor could rescue Opportunity’s solar panels from that fate, a phenomenon that surprised scientists when they first observed it early in the rovers’ careers: a predictable seasonal cycle of winds that are strong enough to blow dust off instruments and rovers. Those wind events should begin, in terrestrial time, in November and last until January, said Harrison, who began her work with the Mars Exploration Rovers team by producing Martian weather forecasts when there were still twin robots.

But it’s not yet clear how that will align with the 45-day window opening after the atmosphere hits 1.5 tau — so, from what NASA has stated publicly so far, engineers trying to reach the rover may not be able to send it active commands at the times when those commands are most likely to work.

The overwhelming team consensus Harrison has heard is that active listening should continue through dust-cleaning season, “which, in the grand scheme of things, is not that long from now,” she said. “You’re not going to suddenly be saving tens of millions of dollars by cutting the mission short.”

Twin rovers, different fates

Harrison and Seibert were both struck by the timeline Opportunity is being offered in comparison to how its twin, Spirit, fared nearly a decade ago, when its travels came to an abrupt end. “We did everything we could have done: Spirit was in much worse condition going into that fourth winter than Opportunity was going into the dust storm,” Seibert said. “Spirit had much less of a chance of actually returning to contact with Earth than Opportunity does now.”

In April 2009, Spirit got stuck in a position that meant the robot lost power when winter came, likely freezing vital electronics on the rover. The team left the robot alone over the Martian winter, but in July 2010, NASA began an intensive, 11-month-long listening campaign that blended active and passive listening, Seibert said.

Anywhere from three times a week to daily, the team would call Spirit, performing what they nicknamed a “sweep and beep” maneuver. That included one procedure to force the rover’s radio to a specific frequency and a second to cue a signal. Sessions usually lasted an hour but occasionally stretched as long as 5 hours, and they took place day and night to fit the Martian schedule.

Between those active-listening sessions, engineers with the Deep Space Network, which communicates with Martian missions, automatically scanned their feeds for signals that may have come from the trapped rover.

After nary a whisper, NASA declared the rover permanently dead in May 2011. That decision came after a meeting with all the senior team members, which Seibert said he remembers well. “It was a very purely democratic discussion,” he said, adding that he was the first to hesitantly suggest giving up on Spirit, focusing the mission’s resources on Opportunity alone.

“It hurt to say, but in my mind, I was OK saying it, because we had done so much to try to recover Spirit and the odds were so much against that rover,” he said. And back then, the team still had a piece of the mission at work. “Mars Exploration Rovers continued on. It was just losing half of the spacecraft, but there was still plenty to do.”

“Shock and awe and sadness”

But there’s no longer a second active rover, and Opportunity scientists and engineers have been publicly speaking out about how demoralizing the rover’s silence is. Earlier this week, they realized that NASA was deciding how to proceed, with one rumor suggesting that the rover would be given 30 days of active listening after tau reached 1.5. On the evening before the meeting deciding the rover’s fate, they enlisted mission allies to launch a Twitter campaign showing public support under the hashtag #SaveOppy. And they saw a flood of responses, which Harrison thinks may have influenced the managers’ decision.

But even a 45-day period isn’t satisfying to her or Seibert, who said that he hasn’t seen the same sort of exhaustive efforts for Opportunity as he and his colleagues conducted for Spirit. “It just seems like it’s an easier thing to say we’re done than putting the extra effort into soldiering on in the face of adversity,” Seibert said. “It still seems like it’s walking away early.”

NASA doesn’t seem to be effectively communicating with current team members about their decisions either, said Harrison, who added that the team didn’t get a heads-up about the Aug. 30 announcement. “It seems pretty arbitrary, because [a] tau of 1.5 is still relatively high and we’re not sure where that number came from. That information has not been released to the team,” she added.

(In addition, tau measurements may not be particularly precise right now. Banfield mentioned that tau is more difficult to measure with confidence when the rover itself is out of order, because Curiosity is on the opposite side of the planet, forcing scientists to rely on images taken by orbiters.)

But Callas, JPL’s project manager for Opportunity, said NASA has to draw the line somewhere, as sympathetic as he is to his grieving colleagues. “It’s just like a loved one that’s missing in action — the more time that passes, the less likely you are” to hear anything, he said. “I mean, you still hold out hope, and we are. We’ll still listen. But we have to be realistic, too, as difficult as that is emotionally.”

Other Opportunity team members may not be there yet, still focused on hoping for the best for the robot they’ve tended to for more than a decade. And the emotional strain is reaching beyond engineers in mission control.

“It’s killing me not to be there and not to be in the trenches with that team working on the problem,” Seibert said. He’s told friends still working with the mission to call when they get a signal, so he can jump on a plane and foot the bill for celebratory drinks. “I really hope I get that phone call soon.”