Stocks enter the typically rocky month of September at historic highs, and this year the odds are even greater than normal that something big could jolt markets.

Statistically, September is the worst month of the year for stocks, and while the S&P 500 is up about 9 percent so far this year, strategists say what’s ahead this fall could challenge those gains, including the U.S. midterm elections.

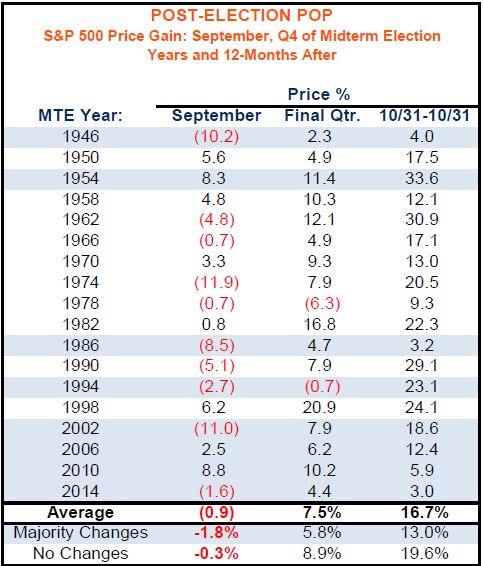

In years when there are midterm elections, CFRA says the returns have been erratic, and the S&P has averaged a 1 percent decline in September, going back to 1946. But it’s often just temporarily bad news for the market, if history is a guide. In those midterm years, the market most often has rallied in the final quarter for an average gain of 7.5 percent.

But Ethan Harris, head of global economics at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, lists a number of global disputes coming to a head this fall, including tariffs on imports from China, the potential for auto tariffs on other countries, Iran oil sanctions kicking in, Congress facing another budget deadline and the election in November. “The risk calendar gets quite big this fall,” he said. “September is part of it, but it’s really the whole fall period.”

September is also when the Fed is next expected to raise interest rates, and its post-meeting statement Sept. 26 and comments from Fed Chairman Jerome Powell could signal how strongly the Fed views its forecast for a December hike. David Ader, chief macro strategist at Informa Financial Intelligence, said Powell was not as dovish at Jackson Hole last week as some may have thought.

“The odds for a December hike are now higher than they’ve been,” he said. “I suspect we’re going to get a Fed that’s going to indicate it’s going to hike again. There are real risks for the stock market that go beyond the mere fact it’s September.”

David Bianco, Americas CIO at DWS, is expecting a stock sell-off this fall. “We think a 5-9 percent dip is likely this autumn, but worse than that is also a possibility given the uncertainties,” he wrote in a note, adding the next 5 percent move for the S&P should be lower.

Bianco outlined a whole range of risks, starting with the Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes. A stronger dollar has been one side effect of Fed rate hiking, and it’s already had a negative impact.

The rising dollar has already caused “an emerging market slowdown aggravated by U.S. tariffs, which already contributed to a bear market in China and Turkish lira crash. Dollar upside risk remains as the U.S. Federal Reserve intends to hike despite risks abroad, including a contentious Brazilian Presidential election, Italian budget, Brexit planning,” he added.

Topping the list of threats, however, are the Trump administration’s tactics in trade negotiations with China.

“I think we’re going to work through this continued intersection of domestic and international political risk, with the fact the economy is very good and the earnings projection is very good, and the valuations are creeping up, but they’re by no means excessive, with interest rates at this level,” said Julian Emanuel, chief equity and derivatives strategist at BTIG. “But our view has been all along that basically you’ve got to fix the relationship with China in order to really make material further upside progress.”

Strategists said the big risk in September is that the White House could decide to unleash another wave of tariffs on Chinese products, this time on $200 billion in Chinese imports. China has said it would retaliate with tariffs on another $60 billion in U.S. goods.

It’s not clear whether the administration will proceed with the threat, but some strategists believe it could.

“Maybe it’s a calculation that raising the temperature and slapping these tariffs on will play better coming into November, but our view is that’s one of the potential headwinds facing the market moving into September,” Emanuel said. China is not expected to return to negotiations until after the outcome of the election is clear. “China basically realized … there’s a potential for their negotiating position to improve.”

Emanuel said he is concerned with the volatility index known as the VIX being at a low of 12 in the month of August while September is often seasonally weak. “That is concerning us. Volatility is too low, period,” he said.

Harris said the $200 billion in tariffs could be what turns the current trade friction into an out-and-out trade war. He said those tariffs could begin to affect the U.S. consumer.

“The trade war is kind of an abstract thing right now. No one is feeling it unless they are in one of these narrow industries that are getting hit,” Harris said. “It’s not really a war at this stage; it’s really more of a skirmish.”

Trade issues with Mexico and Canada, as of Wednesday, appeared nearing a resolution as three-way talks were underway in Washington, but Harris said there is still a risk for 25 percent tariffs on European autos threatened by Trump. Those tariffs and others are on hold while talks are underway.

“If I’m going to rank the risks this fall, trade wars are one. Iran oil sanctions are two, then the European crisis is three. You have the Italian budget, due at the end of September, which is a very contentious thing, where the government promised a budget the European Commission is very likely to reject,” said Harris. “I think you’ve already seen a foretaste with the Italian bond yields spiking up and staying higher.”

Harris said the markets are also watching the progress of the U.K.’s pending exit from the European Union next March. On Sept. 30, the U.K. conservative party conference begins, and its tone could influence the course of Brexit talks. He said it would take a big shock from Europe to affect the U.S. Failure by the U.K. to reach a Brexit deal could be such an event.

“There’s a lot of unfinished business that’s just piling up,” Harris said, listing a lack of progress on denuclearizing North Korea, the still-unratified handshake deal on trade between South Korea and the U.S., China tariffs and Iran sanctions.

Harris said the U.S. sanctions on Iran oil exports, starting in November, could be an issue if the Trump administration succeeds in taking as much oil off the market as it has said it is seeking. It has said it wants all Iranian oil off the market, about 2.3 million barrels a day.

Analysts say it’s possible about 1 million barrels could be off the market by year-end. A much larger amount would squeeze supply and affect prices, Harris said. Already, companies have announced that they will step back from dealing with Iran, and Harris said the sanctions could create tensions between the U.S. and five countries that remain in the Iran nuclear deal. The U.S. broke from that group and decided on its own to reapply sanctions.

The midterm elections add the potential for volatility to an already negative return month for stocks. September has been the worst month for the Dow and the S&P 500 since 1950, according to data from “Stock Trader’s Almanac.” The Dow averages a decline of 0.7 percent, while the S&P 500 loses 0.5 percent on average in September.

The uncertainty around the election is what causes the turmoil, and there has been concern Republicans could lose one or both houses of Congress.

However, Harris said the market could be less concerned about the election than other factors.

“It’s not like you’re going into the election highly uncertain about the future. Most of the risk factors, most policy uncertainty now is not around Congress, it’s about the administration,” he said. “It’s unilateral actions taken by the administration. Congress is kind of a sideshow.”

Democrats, if successful in gaining a majority in one or both houses, could change some things, but the major economic policy changes are in place with the tax cuts passed last year, and stimulus spending, he said.

Another risk for stocks in September is coming from the bond market. First the yield curve, or the difference between short-duration and longer-duration rates, is narrowing. That so-called flattening is a warning sign about the economy. If it inverts, meaning short-term rates spike above longer-term rates, it’s a recession warning, market pros say.

“We’ve said the markets and economy can survive a flat yield curve,” said Emanuel. “They did it well from spring of ’97 to spring of 2000. In the middle it inverted in the aftermath of the Asian currency crisis.”

The Fed’s rate hikes have been driving up the 2-year yield, now at 2.66 percent, just 22 basis point below the 10-year yield.

The closely watched 10-year Treasury note was at 2.88 percent Wednesday, but a much higher yield on the 10-year could be a risk for stocks.

“What is a concern is when you get materially above 3 percent on the 10-year,” Emanuel said. One thing that can contain the rise in Treasury yields could be a stock market sell-off, which would trigger a flight to safety into bonds.

Bond strategists have been warning that the second half of September could bring a slight jump in yields because pension funds have been loading up on Treasurys and other bonds before the Sept. 15 deadline for a change in tax laws for corporate sponsors of funds. They believe that buying has depressed yields, which move opposite prices, and the end of those purchases could send yields higher.

After Sept. 15, companies will no longer be able to deduct pension contributions at last year’s higher tax rate, and will begin deducting at the new 21 percent rate.

“They’re going to stop putting money into the stock market by that same function, and you’re getting into the end of the year,” Ader said. Pension funds for the S&P 1500 are now funded at an average of 91 percent for the first time in years. As many funds are legacy funds, strategists expect them to reduce risk because they want to secure their funding levels.

“They may at least take some chips off the table,” said Ader. “The funding levels are so close to where they need to be after a strong performance by the equity market and a strong performance by the investment-grade bond market.”