For the first time, researchers were able to study quantum interference in a three-level quantum system and thereby control the behavior of individual electron spins. To this end, they used a novel nanostructure in which a quantum system is integrated into a nanoscale mechanical oscillator in form of a diamond cantilever. Nature Physics has published the study, which was conducted at the University of Basel and the Swiss Nanoscience Institute.

Electron spin is a fundamental quantum mechanical property. In the quantum world, the electronic spin describes the direction of rotation of the electron around its axis, which can normally occupy two so-called eigenstates commonly denoted as “up” and “down.” The quantum properties of spin offer interesting perspectives for future technologies, for example, in the form of extremely precise quantum sensors.

Combining spins with mechanical oscillators

Researchers led by Professor Patrick Maletinsky and Ph.D. candidate Arne Barfuss from the Swiss Nanoscience Institute at the University of Basel report in Nature Physics a new method to control the quantum spin with a mechanical system.

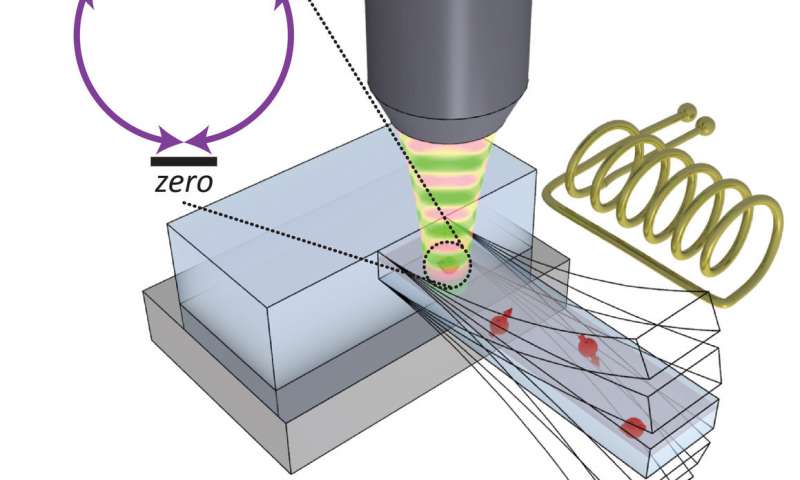

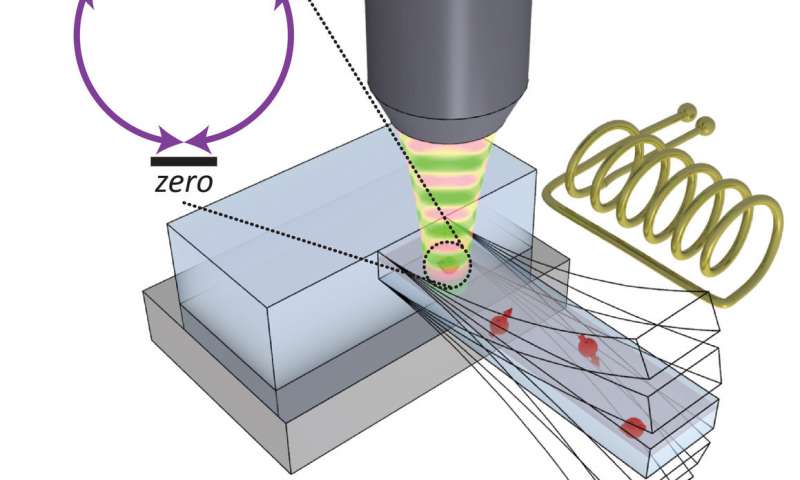

For their experimental study, they combined such a quantum system with a mechanical oscillator. More specifically, the researchers employed electrons trapped in so-called nitrogen-vacancy centers and embedded these spins in single-crystalline mechanical resonators made from diamond.

These nitrogen-vacancy spins are special, in that they possess not only two, but three eigenstates, which can be described as “up,” “down” and “zero.” Using the special coupling of a mechanical oscillator to the spin, they showed for the first time complete quantum control over such a three-level system, in a way not possible before.

In particular, the oscillator allowed them to address all three possible transitions in the spin and to study how the resulting excitation pathways interfere with each other. This scenario, known as “closed-contour driving,” has never been investigated before, but opens interesting fundamental and practical perspectives. For example, their experiment allowed for a breaking of time-reversal symmetry, which means that the properties of the system look fundamentally different if the direction of time is reversed than without such inversion. In this scenario, the phase of the mechanical oscillator determined whether the spin circled “clockwise” (direction of rotation up, down, zero, up) or “counter-clockwise.”

This abstract concept has practical consequences for the fragile quantum states. Similar to the well-known Schrödinger’s Cat thought experiment, spins can exist simultaneously in a superposition of two or three of the available eigenstates for a certain period, the so-called quantum coherence time.

If the three eigenstates are coupled to each other using the closed contour driving discovered here, the coherence time can be significantly extended, as the researchers were able to show. Compared to systems in which only two of the three possible transitions are driven, coherence increased almost a hundred-fold. Such coherence protection is a key element for future quantum technologies and another main result of this work.

The results have high potential for future applications. It is conceivable that the hybrid resonator-spin system could be used for the precise measurement of time-dependent signals with frequencies in the gigahertz range—for example, in quantum sensing or quantum information processing. For time-dependent signals emerging from nanoscale objects, such tasks are currently very difficult to address otherwise. Here, the combination of spin and an oscillating system could be useful, in particular because of the demonstrated protection of spin coherence.