Curiouser and curiouser: Strange metals are getting a little stranger.

Normal metals such as copper and aluminum are old hat — physicists have a strong grasp on the behavior of the electrons within. But strange metals behave in mysterious ways, and researchers have now uncovered an additional oddity. A type of strange metal called a cuprate behaves unexpectedly when inside a strong magnetic field, the team reports in the Aug. 3 Science.

Strange metals are “really one of the most interesting things to happen in physics” in recent decades, says theoretical physicist Chandra Varma of the University of California, Riverside, who was not involved with the research. The theory that explains the behavior of standard metals can’t account for strange metals, so “a completely new kind of fundamental physics” is needed.

The metallic curios’ idiosyncrasies relate to their resistivity — how difficult it is for electric current to flow through them. As scientists crank up a strange metal’s temperature, its resistivity increases in lockstep: Double the temperature and you double the resistivity. That’s unusual: In most metals, the change in resistivity is more complex. For example, at low temperatures, the resistivity of a normal metal like copper would hardly change as the temperature inched up.

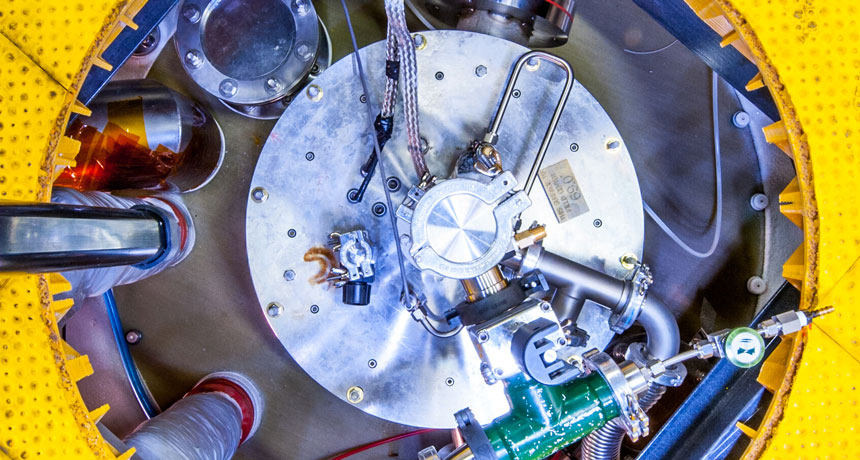

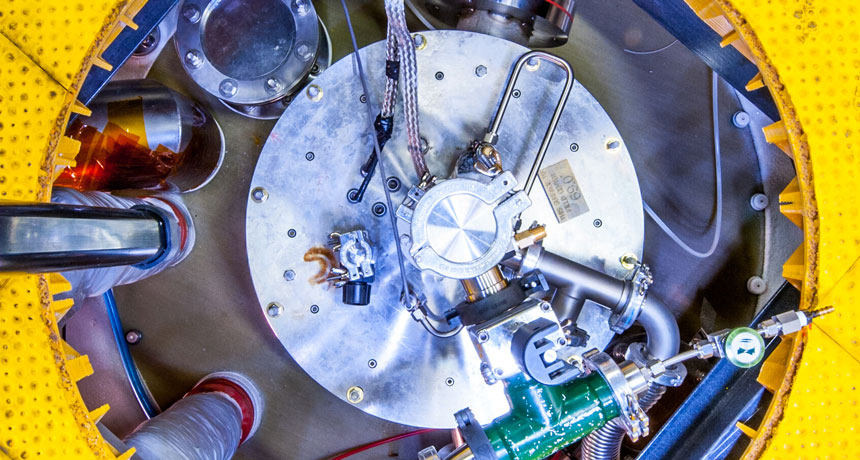

Strange metals’ behavior flouted the norms of physics, attracting scientists’ attention. The materials were “poking in our eye much more than other materials,” says physicist Arkady Shekhter of the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory in Tallahassee, Fla. So he and colleagues studied how the cuprate behaved in extremely strong magnetic fields, up to almost 2 million times the strength of Earth’s magnetic field.

The researchers showed that when the magnetic field is ramped up, the strange metal exhibits similarly weird behavior as it does with temperature. As the magnetic field grows, resistivity in the cuprate increases apace. It’s what’s known as a linear relationship, because it looks like a diagonal straight line when plotted on a graph showing resistivity versus magnetic field. In a normal metal, the change in resistance with the increasing magnetic field would be smaller, and would not be a straight line, instead curving.

Besides being strange metals, cuprates have another claim to fame: Under certain conditions, cuprates become superconducting, transmitting electricity without resistance (SN: 1/20/18, p. 11). While most superconductors have to be cooled to nearly absolute zero, cuprates operate at significantly higher temperatures. That makes the superconductors easier to use in technological applications, where the elimination of resistance could allow for more efficient, better performing electronics. Studying strange metals could help scientists better understand how cuprates superconduct at higher temperatures.

The result is “a really amazing discovery,” says physicist Jiun-Haw Chu of the University of Washington in Seattle, who was not involved with the research. “There’s a symmetric role that is played by temperature and field, and that is really new.”