Hopes are rising again for a drug to alter the course of Alzheimer’s disease after decades of failures. An experimental therapy slowed mental decline by 30 percent in patients who got the highest dose in a mid-stage study, and it removed much of the sticky plaque gumming up their brains, the drug’s makers said Wednesday.

The results have been highly anticipated and have sent the stock of the two companies involved soaring in recent weeks.

The drug from Eisai and Biogen did not meet its main goal in a study of 856 participants, so overall, it was considered a flop. But company officials said that 161 people who got the highest dose every two weeks for 18 months did significantly better than 245 people who were given a dummy treatment.

There are lots of caveats about the work, which was led by company scientists rather than academic researchers and not reviewed by outside experts. The study also was too small to be definitive and the results need to be confirmed with more work, dementia experts said. But they welcomed any glimmer of success after multiple failures.

“We’re cautiously optimistic,” said Maria Carrillo, chief science officer of the Alzheimer’s Association, whose international conference in Chicago featured the results.

“A 30 percent slowing of decline is something I would want my family member to have,” and the drug’s ability to clear the brain plaques “looks pretty amazing,” she said.

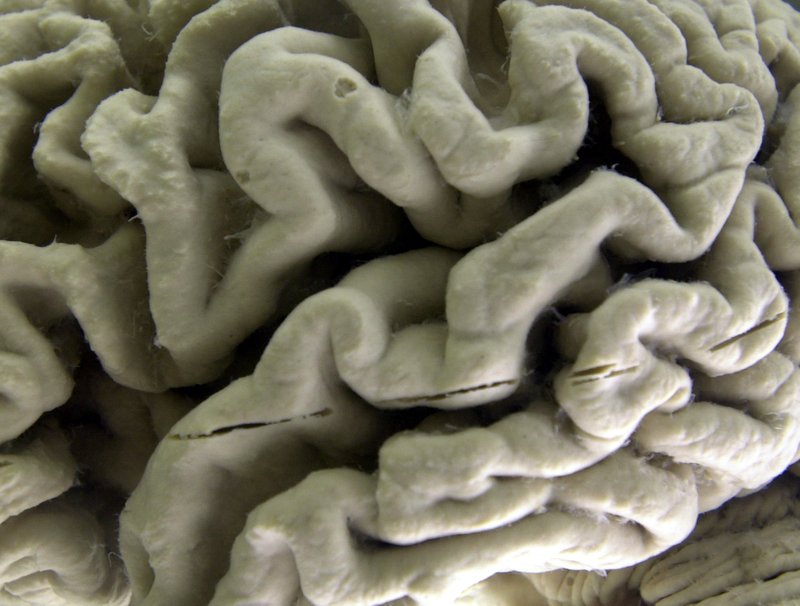

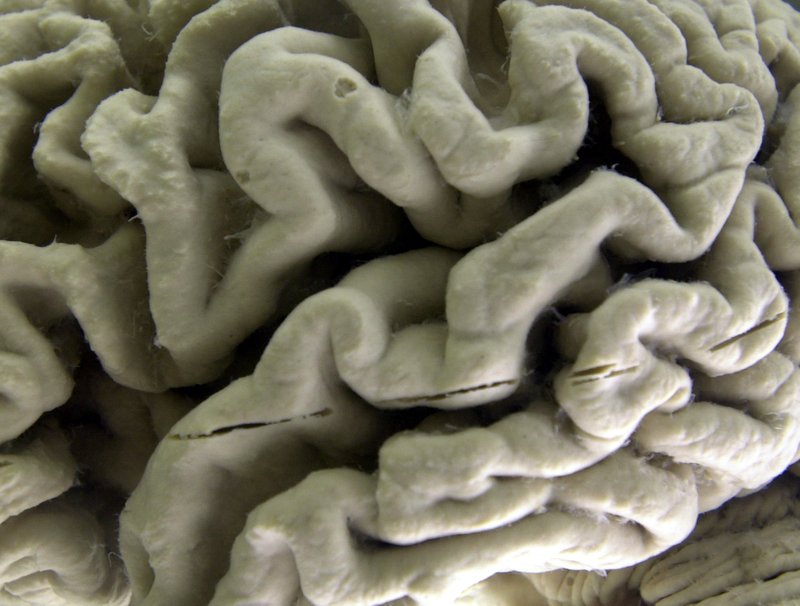

About 50 million people worldwide have dementia, and Alzheimer’s is the most common type. There is no cure— current medicines just ease symptoms. Some previous efforts to develop a drug to slow the disease may have been tried too late, after much damage had already occurred. The new drug aimed sooner, in people with early Alzheimer’s, and the drug works at an earlier step in formation of the sticky brain plaques.

Study participants were given one of five doses of BAN2401 or a dummy treatment via IV. After one year, the companies said the drug didn’t meet statistical goals. But after 18 months, they saw a benefit in the highest dose group.

What makes it tricky, though, is that they used a new way to measure mental decline, a scale that combines parts of three other widely used tests. This is the first study to use that measure, and it’s unclear how much of a difference a 30 percent slowing of decline makes — whether it allows someone to continue to bathe or feed himself, for instance.

“It’s intriguing, but these are designs we’re not used to seeing,” and it will require more study for doctors to feel comfortable with this as a measure of success, said one independent expert, Dr. Julie Schneider of Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

On one traditional measure of thinking skills, those at the highest dose declined 47 percent less than people given a dummy treatment.

Brain scans added evidence that the drug might be effective. All participants had signs of the sticky plaques that are the hallmark of Alzheimer’s at the start of the study, but 81 percent of people on the highest dose saw all signs of them disappear after 18 months, an Eisai official said.

Side effects leading to discontinuation of treatment occurred in 19 percent of those on the high dose and 6 percent of the dummy treatment group. Cases of brain swelling, which have been seen in other treatments targeting the plaques in the brain, occurred in two people in the placebo group and 16 of those in the high dose group.

Other dementia experts were encouraged.

“That’s a very hopeful outcome. It means we may be on the right track,” said another scientist with no role in the work, Dr. Stephen Salloway, neurology chief at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

Dr. Reisa Sperling, a neurologist at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said it’s important to realize that this is not a cure, just possibly a slowing of decline.

“We’re not suddenly returning people back to their pre-Alzheimer’s baseline,” she said.

Dr. Lynn Kramer, chief medical officer of Eisai’s neurology unit, said the companies would talk with regulators about further studies.

Shares of Biogen, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Eisai, based in Tokyo, soared after July 5 when they announced that the drug had slowed the progression of early Alzheimer’s disease for certain patients. Biogen’s stock jumped 19.6 percent in one day, its biggest move in 14 years, and has continued to rise. Eisai rocketed 40 percent in two days.

Biogen stock gyrated in aftermarket trading after the study results were released. After switching between gains and losses several times, it fell 6.5 percent.