A fringe theory about the origins of Alzheimer’s disease—that latent viral infections can sometimes trigger its emergence—has gotten perhaps its most significant bit of support yet. A complex new study published Thursday in Neuron has found evidence that certain viruses are not only more common in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s, but that they play a direct role in the chain of events responsible for the fatal neurodegenerative disorder.

As study author Joel Dudley, an associate professor of genetics and genomic sciences at Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine, is quick to mention, the findings were anything but expected.

“We actually had no intentions of looking at this theory. We were actually looking for new drug targets,” he told Gizmodo. “But by taking this data-driven approach on an exciting new data set, we were led down this path of looking at viruses.”

Dudley and his team studied brain samples taken from people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s after death, and compared them to samples from people who had died free of the disease. The data from these samples was collected from three large brain banks by the National Institutes of Health, via their Accelerating Medicines Partnership-Alzheimer’s Disease (AMP-AD) consortium. That was important because it provided the team access to the raw genomic sequences of these brains. Ordinarily, in these sort of studies, scientists can only look at the genes explicitly known to be human, but the NIH data allowed them to sequence and identify genetic material belonging to viruses that had made their home in the brain.

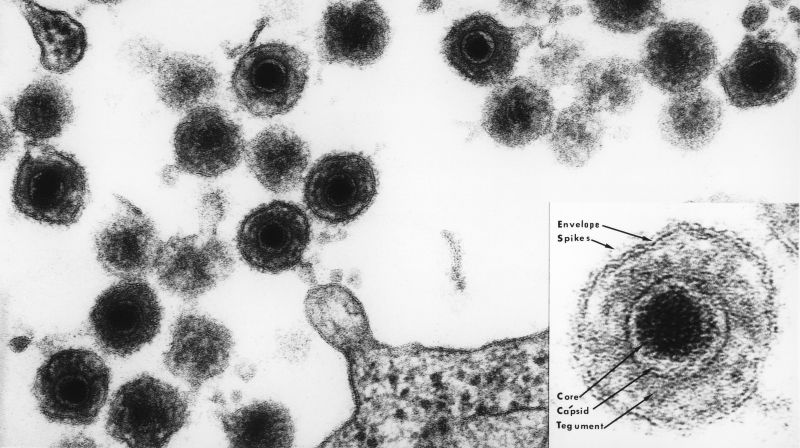

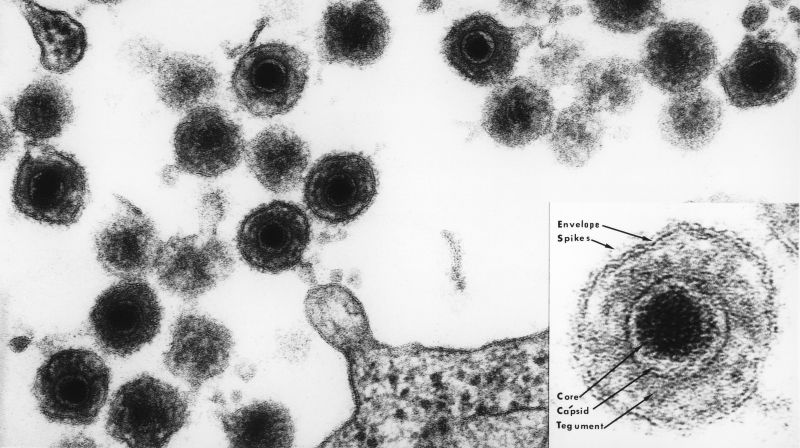

Based on that genetic footprint, the team found several species of herpesviruses that were more common in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s. Greater amounts of herpesvirus found in the brain were also associated with someone having a worse level of dementia before their death, further suggesting a clear link. And of all the viruses they looked at, there were two that showed the strongest connection to Alzheimer’s: human herpesvirus 6A (HHV-6A) and human herpesvirus 7 (HHV-7).

“That was just the beginning of the thread we started pulling on,” Dudley said. “Just because we found greater abundance in the Alzheimer’s cases, that doesn’t rule out the possibility that these viruses could just be passengers.”

So Dudley’s team went one step deeper. They used the data to create computer models of how the genes in a person’s brain interacted with any viral DNA and RNA also found there. The models suggested that HHV-6A and HHV-7 genes were regularly turning on and off human genes in these brains, and vice-versa. And the human genes that most interacted with HHV-6A and HHV-7 were also genes that have been previously implicated in raising someone’s risk of Alzheimer’s. These interactions were also found in areas of the brain especially affected by the disease, such as the hippocampus.

“We could see that the viruses were potentially activating known Alzheimer’s genes and suppressing other genes [thought to be related to the disease],” Dudley said. “So these viruses could perhaps be the environmental factor that trigger someone’s genetic susceptibility to Alzheimer’s.”

The researchers had no interest in proving or disproving the so-called viral hypothesis of Alzheimer’s when they started, but Dudley feels that makes their results all the more convincing. Regardless, the study is welcome validation for some researchers who have doggedly argued for a viral origin.

“My main reaction on seeing this article was pleasurable, as it adds a further study to the steadily increasing number of papers that support a microbial role in Alzheimer’s,” said Ruth Itzhaki, a professor emeritus of molecular neurobiology at Britain’s University of Manchester who has argued for the hypothesis since at least 1991. “The numbers are particularly gratifying in view of the derision and vituperative hostility to the concepts that some of us endured for decades—with the consequent extreme problems in funding the work and in publishing the results.”

The majority of research into the viral hypothesis, including Itzhaki’s, has mainly focused on a different herpesvirus, though: Herpes simplex 1 (HSV-1), otherwise known as the culprit behind cold sores. Of more than 130 studies that have found indirect evidence of a viral link, Itzhaki notes, only a few have singled out HHV.

Dudley’s team did find an association between HSV-1 and Alzheimer’s, just not to the same degree as HHV-6A and HH7. And he doesn’t think the results discount the possibility that HSV-1 could be involved. But because HSV-1 is relatively easier to detect through blood tests, he also suggests that researchers relying on older methods could have simply missed a stronger link between Alzheimer’s and HHV.

HHV-6A and HHV-7 typically infect people at the same time at a very early age. In children, they cause the mild skin disease roseola. But they’ve also been theorized to cause other neurological disorders. HHV-6 in particular has been repeatedly linked to multiple sclerosis, a degenerative muscle disorder.

But because these viruses are so prolific—HHVs are found in about 90 percent of Americans, while HSV-1 is found in about 50 percent—and not everyone develops Alzheimer’s, it’s clear that viral infections could only be a small, if crucial, piece of the puzzle behind what causes Alzheimer’s.

It’s thought these viruses lie dormant somewhere in the body, only to somehow migrate to and silently infect the brain or nervous system at some point in our lives. But something else must be reactivating them, such as stress or other illnesses that weaken the immune system. And from there, something else must be making people’s brains interact with the viruses in the exact way that accelerates the progression of Alzheimer’s. Itzhaki’s research has suggested, for instance, that HSV-1 largely raises a person’s risk of Alzheimer’s only if they’re carrying the E-4 variation of the APOE gene, which is already a risk factor for the disease.

Dudley’s research, meanwhile, also found that both viruses interacted with the human genes responsible for producing beta-amyloid, the protein that bunches together to form the characteristic plaques that litter and are thought to destroy the brain in Alzheimer’s patients. That finding reinforces another theory that our innate immunity can inadvertently help cause the disease. The theory, which Itzhaki has leaned on as well, suggests that beta-amyloid is used by our brain to defend itself against infection. In people who end up having Alzheimer’s, the defense mechanism somehow goes disastrously wrong.

If that’s the case, Dudley says, then there might be more than one species of virus or even bacteria capable of setting off Alzheimer’s and other neurological conditions.

There’s no shortage of questions about how all these factors work together to cause a disease that now afflicts five million Americans and is only becoming more common. But these findings, along with other recent research supporting the viral hypothesis, provide new clues to follow and hypotheses to test, as well as even new treatments to someday test, such as antivirals. The latter is particularly in sore need, given that just about every treatment for Alzheimer’s to reach clinical trials has so far failed abysmally.

“If this was all so simple, we would have figured it out already,” Dudley said.

The next-generation genetic sequencing methods Dudley and his team plan to continue using might also illuminate an entire world of microorganisms that call our bodies and brains home, many of whom could affect us in ways we simply don’t understand right now.

“We’re probably like an ecosystem of various viral genes plus human genes, some integrated, some latent, and even within our bodies, there’s going to be lots of variety among different cells.” Dudley said. “That’s pretty scary.”