Researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder have helped to find the last reservoir of ordinary matter hiding in the universe.

Ordinary matter, or “baryons,” make up all physical objects in existence, from stars to the cores of black holes. But until now, astrophysicists had only been able to locate about two-thirds of the matter that theorists predict was created by the Big Bang.

In the new research, an international team pinned down the missing third, finding it in the space between galaxies. That lost matter exists as filaments of oxygen gas at temperatures of around 1 million degrees Celsius, said CU Boulder’s Michael Shull, a co-author of the study.

The finding is a major step for astrophysics. “This is one of the key pillars of testing the Big Bang theory: figuring out the baryon census of hydrogen and helium and everything else in the periodic table,” said Shull of the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences (APS).

The new study, which will appear June 20 in Nature, was led by Fabrizio Nicastro of the Italian Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica (INAF)—Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma and the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Researchers have a good idea of where to find most of the ordinary matter in the universe—not to be confused with dark matter, which scientists have yet to locate: About 10 percent sits in galaxies, and close to 60 percent is in the diffuse clouds of gas that lie between galaxies.

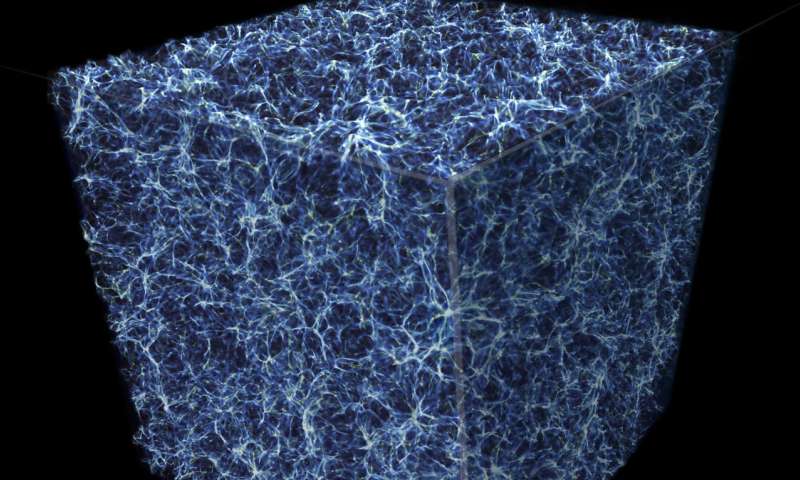

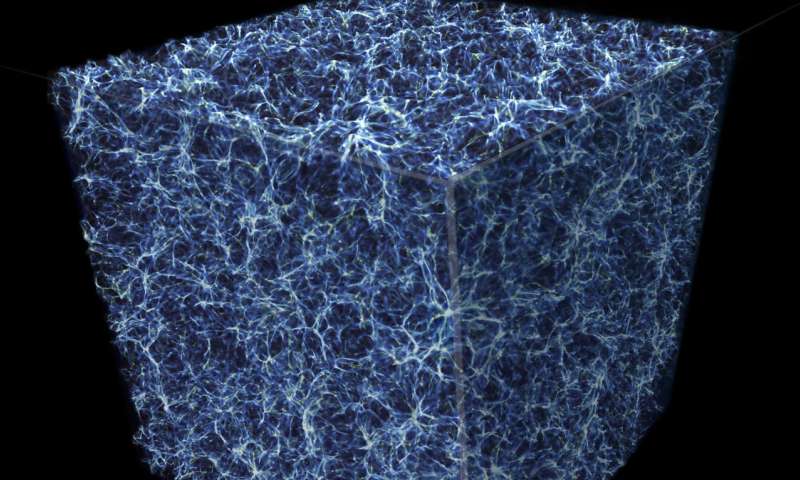

In 2012, Shull and his colleagues predicted that the missing 30 percent of baryons were likely in a web-like pattern in space called the warm-hot intergalactic medium (WHIM). Charles Danforth, a research associate in APS, contributed to those findings and is a co-author of the new study.

To search for missing atoms in that region between galaxies, the international team pointed a series of satellites at a quasar called 1ES 1553—a black hole at the center of a galaxy that is consuming and spitting out huge quantities of gas. “It’s basically a really bright lighthouse out in space,” Shull said.

Scientists can glean a lot of information by recording how the radiation from a quasar passes through space, a bit like a sailor seeing a lighthouse through fog. First, the researchers used the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph on the Hubble Space Telescope to get an idea of where they might find the missing baryons. Next, they homed in on those baryons using the European Space Agency’s X-ray Multi-Mirror Mission (XMM-Newton) satellite.

The team found the signatures of a type of highly-ionized oxygen gas lying between the quasar and our solar system—and at a high enough density to, when extrapolated to the entire universe, account for the last 30 percent of ordinary matter.

“We found the missing baryons,” Shull said.

He suspects that galaxies and quasars blew that gas out into deep space over billions of years. Shull added that the researchers will need to confirm their findings by pointing satellites at more bright quasars.