As soon as sugar touches your tongue, your nervous system kicks into high gear. The tongue tells the brain’s “taste center” that you ate something sweet, relaying a message to another part of your brain that eating sweet stuff is good. This is a problematic process for anyone who’s ever tried to shed some pounds, but now, scientists studying mouse brains have found a way to disrupt it. As researchers write in Nature on Wednesday, just because your brain senses sweetness doesn’t mean it has to conflate sweetness with pleasure.

In their study, the Columbia University researchers disrupted the brain region called the amygdala — responsible for the pleasant or unpleasant experience linked to taste — and found that the mice could still detect bitter and sweet flavors but didn’t express a distaste for one or a preference for the other. This demonstrates that taste isn’t inherently linked to the pleasurable experience of the taste, the authors write. Rather, those two experiences seem to be processed in different brain regions. With this knowledge in mind, the team additionally found that they could hack mouse brains to alter the way mice processed tastes, making plain water pleasurable or distasteful and reversing the way the mice experienced sweet and bitter tastes.

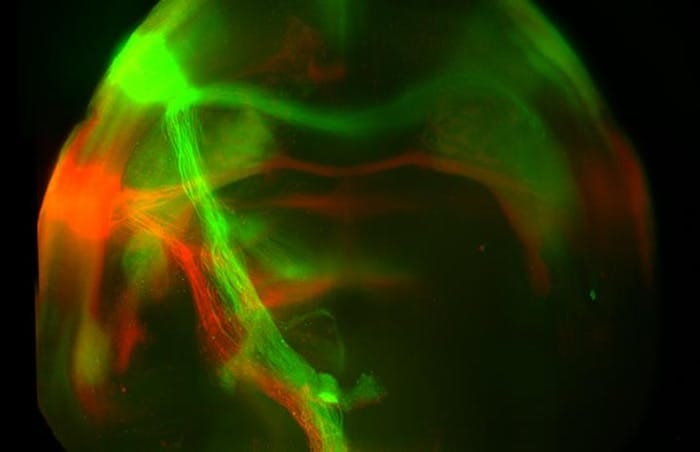

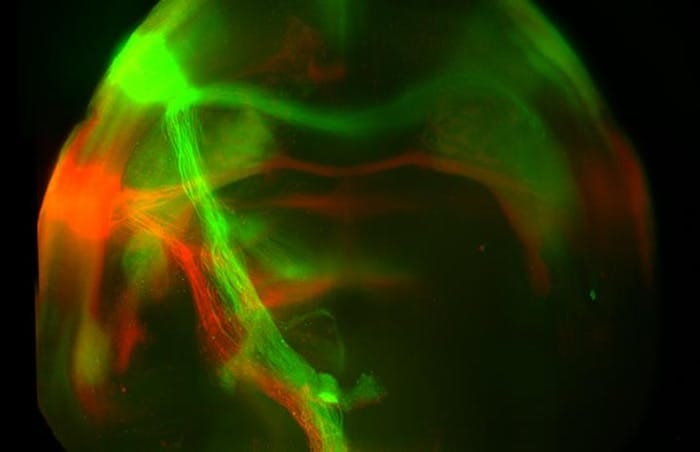

In one set of experiments, the researchers altered the way the mouse brain taste center — the “gustatory cortex” — communicated with the amygdala. The gustatory cortex has separate connection neurons that relay “sweet” and “bitter” signals. So, when the team activated the neurons associated with sweetness, the mice reacted to a neutral stimulus (plain water) as if it was sweet. Likewise, when the neurons associated with bitterness were activated, the mice responded as if it the water was bitter. In this way, they found that this switch could even reverse the mice’s emotional reactions to sweet or bitter tastes.

In another experiment, researchers trained mice to taste water from a spout and identify it as sweet or bitter by going through a door. Then, they silenced the neurons in the amygdala that determine how pleasurable a taste is. These mice were able to identify sweet and bitter, but their appetite for sweetness wasn’t activated, showing that the pleasure-making process was indeed disrupted. In a different test, mice were trained to lick when they tasted something bitter and not lick when they tasted something sweet — the opposite of their natural response. Again, their amygdalae were silenced, and just like the mice in the previous test, they could still recognize sweet and biter, but they didn’t exhibit an emotional response.

These weird experiments demonstrate that tasting and enjoying are governed by separate regions of the brain, at least in mice. If anything, it serves as a reminder that flavor and pleasure aren’t entirely linked, even though most of us take this relationship for granted. By gaining a better understanding of these pathways, which the researchers say are similar in humans, they hope to gain insight into eating disorders, which appear to result from exaggerated responses to food input.

“In the future,” they write, “it will be exciting to unravel how these circuits come together to drive innate and learned responses.”