Like many children, Andrew Hightower, 13, likes pizza, sandwiches and dessert.

But Andrew has Type 1 diabetes, and six years ago, in order to control his blood sugar levels, his parents put him on a low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet. His mother makes him recipes with diabetic-friendly ingredients that won’t spike his blood sugar, like pizza with a low-carb, almond-flour crust; homemade bread with walnut flour instead of white flour; and yogurt topped with blueberries, raspberries and nuts.

Andrew’s diet requires careful planning — he often takes his own meals with him to school. But he and his parents say it makes it easier to manage his condition and, since starting the diet, his blood sugar control has markedly improved and he has not had any diabetes complications requiring trips to the hospital.

“I do this so that I can be healthy,” Andrew, who lives with his parents in Jacksonville, Fla., said of his diet. “When I eventually move out and go to college, I’m going to keep up what I’m doing because I’m on the right path.”

Most diabetes experts do not recommend low-carb diets for people with Type 1 diabetes, especially children. Some worry that restricting carbs can lead to dangerously low blood sugar levels, a condition known as hypoglycemia, and potentially stunt a child’s growth. But a new study published in the journal Pediatrics on Monday suggests otherwise.

It found that children and adults with Type 1 diabetes who followed a very low-carb, high-protein diet for an average of just over two years — combined with the diabetes drug insulin at smaller doses than typically required on a normal diet — had “exceptional” blood sugar control. They had low rates of major complications, and children who followed it for years did not show any signs of impaired growth.

The study found that the participants’ average hemoglobin A1C a long-term barometer of blood sugar levels, fell to just 5.67 percent. An A1C under 5.7 is considered normal, and it is well below the threshold for diabetes, which is 6.5 percent.

“Their blood sugar control seemed almost too good to be true,” said Belinda Lennerz, the lead author of the study and an instructor in the division of pediatric endocrinology at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. “It’s nothing we typically see in the clinic for Type 1 diabetes.”

The new study comes with an important caveat. It was an observational study, not a randomized trial with a control group. The researchers recruited 316 people, 130 of them children whose parents gave consent, from a Facebook group dedicated to low-carb diets for diabetes, called TypeOneGrit, then reviewed their medical records and contacted their medical providers.

While it was not a clinical trial, the study is striking because it highlights a community of patients who have been “extraordinarily successful” at controlling their diabetes with a very low-carb diet, said Dr. David M. Harlan, the co-director of the Diabetes Center of Excellence at the UMass Memorial Medical Center, who was not involved in the study. “Perhaps the surprise is that for this large number of patients it is much safer than many experts would have suggested.”

“I’m excited to see this paper,” Dr. Harlan added. . “It should reopen the discussion about whether this is something we should be offering our patients as a therapeutic approach.”

The authors of the paper cautioned that the findings should not lead patients to alter their diabetes management without consulting their doctors, and that large clinical trials will be necessary to determine whether this approach should be used more widely.

“We think the findings point the way to a potentially exciting new treatment option,” said Dr. David Ludwig, a co-author of the study and a pediatric endocrinologist at Boston Children’s Hospital who has written popular books about low-carb diets. “However, because our study was observational, the results should not, by themselves, justify a change in diabetes management.”

About 1.25 million Americans have Type 1 diabetes, which occurs when the pancreas does not produce enough insulin to regulate blood sugar levels. Managing the condition requires administering insulin throughout the day, especially when consuming meals high in carbs, which raise blood sugar more than other nutrients. Over time, chronically elevated blood sugar can lead to nerve and kidney damage and cardiovascular disease.

The standard approach for people with Type 1 diabetes is to match carb intake with insulin. But the argument for restricting carbs is that it keeps blood sugar more stable and requires less insulin, resulting in fewer highs and lows. The approach has not been widely studied or embraced for Type 1 diabetes, but some patients swear by it.

TypeOneGrit has about 3,000 members on Facebook who ascribe to a program devised by Dr. Richard Bernstein, an 84-year-old physician with Type 1 diabetes. His book, “Dr. Bernstein’s Diabetes Solution,” recommends limiting daily carb intake to about 30 grams, the amount in a sweet potato, large apple or two slices of whole wheat bread.

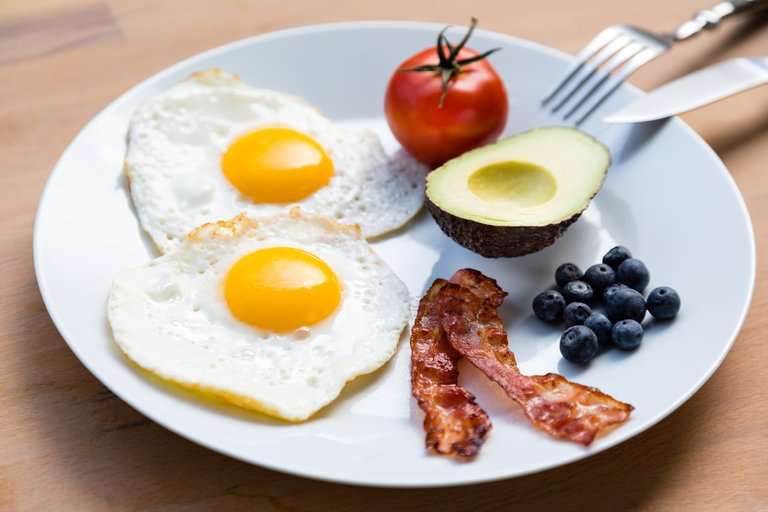

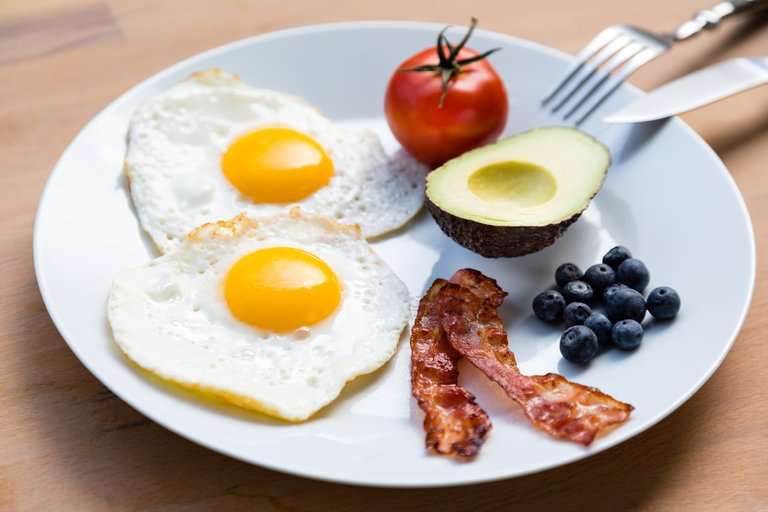

Dr. Bernstein argues that the fewer carbs consumed, the easier it is to stabilize blood sugar with insulin. He recommends foods like nonstarchy vegetables, seafood, nuts, meat, yogurt, tofu and recipes made with soybean flour, sugar substitutes and other low-glycemic ingredients. His plan emphasizes protein intake, which he says is especially important for growing children.

Dr. Carrie Diulus, an orthopedic surgeon with Type 1 diabetes who follows a low-carb vegan diet, credits the Bernstein approach with helping her keep her blood sugar under control. “It allows me to perform complex spine surgeries without worrying about my diabetes because my blood sugar stays relatively stable,” said Dr. Diulus, who helped inspire the new study when researchers learned about her participation in the TypeOneGrit community.

The most striking finding of the new report was that A1C levels, on average, fell from 7.15 percent, in the diabetic range, to 5.67 percent, which is normal. The rate of diabetes-related hospitalizations also fell, from 8 percent before the diet to 2 percent after, including fewer hospitalizations for hypoglycemic seizures.

Those following the diet had increased LDL cholesterol, likely from consuming more saturated fat, which some experts said was potentially concerning and deserved further study. But other heart disease risk factors appeared favorable: They had high HDL cholesterol, the protective kind, and low triglycerides, a type of fat in the blood linked to heart disease.

Dr. Joyce Lee, a diabetes expert at the University of Michigan who was not involved in the study, said the findings were impressive and merited further follow-up, and that patients who wanted to explore a low-carb approach might do so while being monitored by their health care team. But she also noted that the patients in the new study were a “highly motivated” group, and that it would be difficult for many people to adopt the restrictive regimen they followed.

“The reality is that it’s really hard to do low-carb, given our cultural norms,” said Dr. Lee, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan.

In an interview, Dr. Bernstein, a co-author on the paper, said it demonstrates what he sees in his practice: That there are diabetics on his regimen “who are walking around with normal blood sugars and they are happy about it, healthy, and growing if they are kids.”

Derek Raulerson, 46, a human resources manager in Alabama, agrees. Both he and his son, Connor, 13, have Type 1 diabetes. Mr. Raulerson said he struggled for years to control his blood sugar. But six years ago, he gave up juice, bread, potatoes and other simple carbs, and made protein and nonstarchy vegetables the focus of his meals.

Since going low-carb, he said, he has lost weight, cut in half the amount of insulin he uses daily, and watched his A1C fall from the diabetic range to normal levels.

“I have normalized, steady blood sugars now,” he said. “I am no longer on the roller coaster.”