Reality may be made up of multiple universes, but each one may not be so different to our own, according to Stephen Hawking’s final theory of the cosmos.

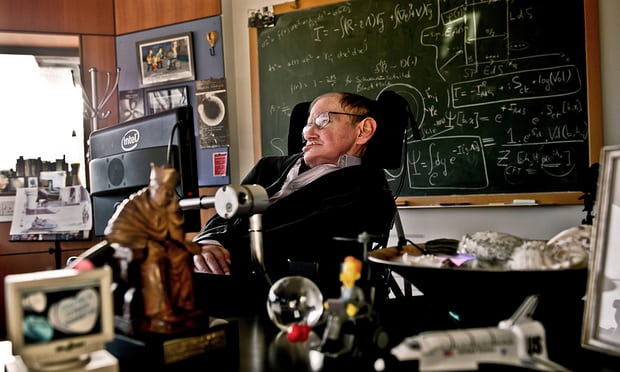

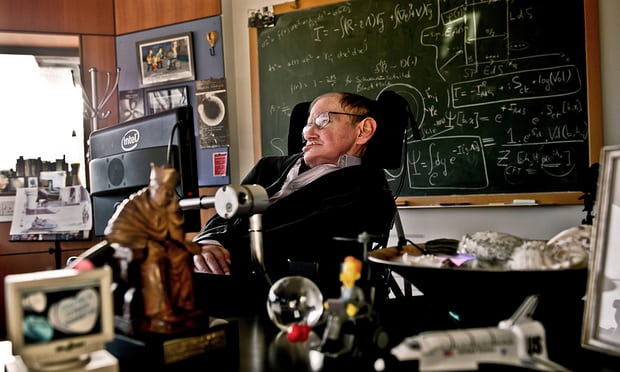

The work, completed only weeks before the physicist’s death in March, paints a simpler picture of the past 13.8 billion years than many previous theories have proposed.

Published on Wednesday in the Journal of High Energy Physics, the new work is the result of a long collaboration with Thomas Hertog, a Belgian physicist at the Catholic University of Leuven. “We sat on this one for a very long time,” Hertog said. “I do believe he was really fond of it.”

Hertog travelled to Cambridge to work on the theory with Hawking and towards the end, communication became very difficult, he said. “I always had the impression that he never wanted to quit and, in a way, this was Hawking. He never showed any sign of wanting to quit.”

“It was never said between us that this would be the last paper. I personally felt this might be the conclusion of our journey, but I never told him.”

Modern physics has more than one theory of how the universe came to be, but one of the most popular ideas is that the big bang was followed by repeated bursts of ‘cosmic inflation’ which created an endless number of ‘pocket universes’ that are now scattered throughout space.

“The usual theory of eternal inflation predicts that globally our universe is like an infinite fractal, with a mosaic of different pocket universes separated by an inflating ocean,” Hawking said last autumn.

But in the latest work, Hawking and Hertog challenge that view. Instead of space being filled with pocket universes where radically different laws of physics apply, these alternate universes may not actually vary that much from one another.

While the consequences of the proposal may not be obvious, the theory may provide some comfort to physicists who wonder how, given all the hostile variations thought possible, we find ourselves in a universe well-suited to life.

“In the old theory there were all sorts of universes: some were empty, others were full of matter, some expanded too fast, others were too short-lived. There was huge variation,” said Hertog. “The mystery was why do we live in this special universe where everything is nicely balanced in order for complexity and life to emerge?”

“This paper takes one step towards explaining that mysterious fine tuning,” Hertog added. “It reduces the multiverse down to a more manageable set of universes which all look alike. Stephen would say that, theoretically, it’s almost like the universe had to be like this. It gives us hope that we can arrive at a fully predictive framework of cosmology.”

The new theory takes work that Hawking and the US physicist James Hartle published in the 1980s and updates it with the more powerful, modern mathematical techniques used in string theory. In string theory, reality is described through the interactions of one-dimensional objects known as cosmic strings.

“Stephen himself said that this work was the area he was most proud of,” said Malcolm Perry, a colleague of Hawking’s at Cambridge University. The new paper will not be the last to bear Hawking’s name, however. With Andrew Strominger at Harvard, Perry has written at least two papers with Hawking on black holes which are still being readied for publication.

Hawking, who rose to fame on the back of his bestselling book, A Brief History of Time, died on 14 March, aged 76, at his home in Cambridge. His ashes will be interred at Westminster Abbey near the grave of Sir Isaac Newton during a thanksgiving service later this year.

Hertog believes that his work with Hawking is one small step towards a theory of our cosmic origins that physicists could ultimately test. If the universe has evolved as the theory predicts, he says, it may have left a telltale signature on gravitational waves, or the so-called cosmic microwave background, the radiation that was released at the birth of the universe. “There may be clues in those signals as to whether or not we are on the right tracks,” he said.

”I’m reasonably hopeful that both further observations and further work on the theory will eventually enable us to test our models of the big bang,” Hertog added. “We are not doing this for Platonic pleasure. Though it is fun.”