NASA will likely launch its first astronauts into deep space since the Apollo program on a less powerful version of its Space Launch System rocket than originally planned. Although it has not been officially announced, in recent weeks mission planners at the space agency have begun designing “Exploration Mission 2” to be launched on the Block 1 version of the SLS rocket, which has the capability to lift 70 tons to low Earth orbit.

On Thursday, during a Congressional hearing, the agency’s acting administrator, Robert Lightfoot, confirmed that NASA is seriously considering launching humans to the Moon on the Block 1 SLS. “We’ll change the mission profile if we fly humans and we use the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS), because we can’t do what we could do if we have the Exploration Upper Stage,” Lightfoot said.

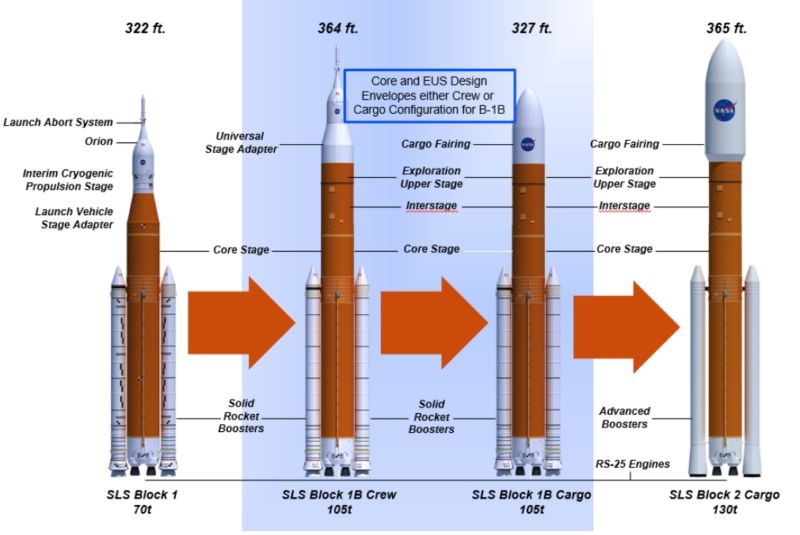

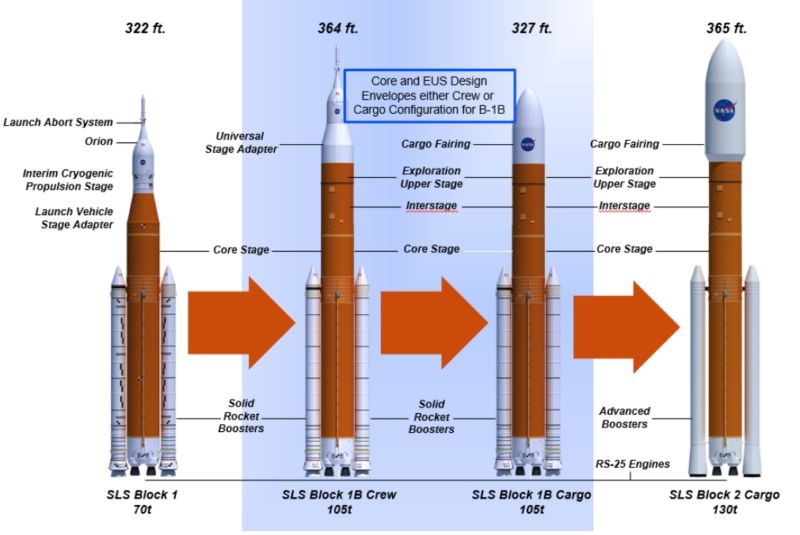

The key difference between the original configuration of the SLS rocket—which NASA has spent more than $10 billion developing since 2011—and its successor is the upper stage that sits atop the booster. Under current plans, the weaker upper stage, known as the ICPS, was to fly only once—on the maiden flight of the SLS rocket in 2020. Then, NASA was to switch to a new, much more powerful second stage that would increase the SLS rocket’s overall performance by about 50 percent.

Now, NASA will probably fly the SLS rocket in its Block 1 configuration at least two or even three times before it debuts the more powerful variant of the booster. By doing so, it may get humans into deep space faster. The current launch date of 2023 for the deep space Exploration Mission 2 could move forward, a NASA spokeswoman confirmed. “The earliest possible launch date is being assessed, with a formal decision expected in the coming months,” she added.

However, this decision also suggests the agency remains far from developing the powerful Exploration Upper Stage, which NASA says it needs to carry out an ambitious program of lunar exploration. This may well delay meaningful exploration in and near the Moon into the mid- and late-2020s, at the earliest.

Mobile launcher

Until a couple of weeks ago, NASA didn’t have the option of flying crew on an ICPS upper stage. Thanks to Congress, however, the agency can now consider flying the Block 1 version of the SLS rocket multiple times. Last month, as part of the fiscal year 2018 budget deal, Congress appropriated $350 million for a new piece of hardware—a mobile launch tower to be built at Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

NASA already has one of these massive towers, which supports the testing and servicing of the SLS rocket, as well as moving it to the launchpad and providing a platform from which it will launch. After the first flight of the SLS rocket, NASA had planned to spend 33 months rebuilding the tower to handle the larger, more powerful version of the SLS with the Exploration Upper Stage. With the additional Congressional funding, it can now start building that second tower and continue to use the existing mobile launch tower for Block 1 SLS launches.

Lightfoot said Thursday that the agency was only beginning to process how best to use this Congressional largesse, which had not been sought in the White House budget. “You’re going to have to give us a little time—it was just a couple of weeks ago that we found out we were getting that—to be able to understand the flow,” Lightfoot said.

Upper-stage delays

NASA’s consideration of flying the first crewed mission into deep space on an SLS rocket with the ICPS upper-stage buttresses the notion that the space agency is struggling with development of the Exploration Upper Stage. Sources have told Ars that the cost of this program has grown beyond expectations. Originally, this 18-meter-tall stage was to be powered by four RL-10 rocket engines. However, in a solicitation late last year, NASA indicated it was looking for lower-cost engines to power the stage. NASA has issued other solicitations to industry, too, that suggest it is concerned about the cost of the upper stage.

During an interview this week, former space shuttle program manager Wayne Hale, who is a member of NASA’s Advisory Council, said it will probably take four or five years for development and construction of the Exploration Upper Stage from this point onward.

“You’re building an entirely new rocket,” Hale said. “It’s not just a tank with some engines bolted onto it. It has to be aerodynamic. It has to be able to take the shock and vibration of launch. It’s got to be started pretty much from scratch. So yeah, it’s complicated.”

Trade-offs

Launching at least one crewed mission or more with the basic, Block 1 rocket buys NASA time for development of the new upper stage, without the embarrassment of long gaps between flights of the SLS rocket. But the decision does not come without its challenges, either. No astronauts have ever flown on a rocket with the ICPS, so it would have to undergo a time-consuming and costly process of “human-rating” the hardware.

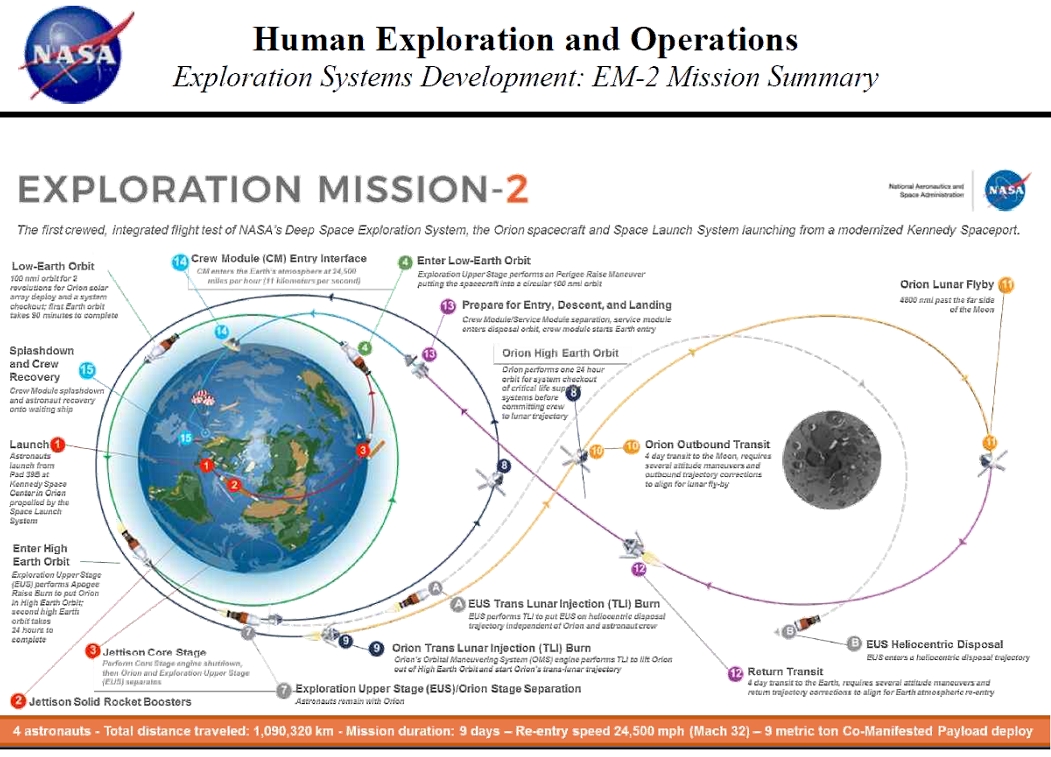

With the ICPS, the flight profile for Exploration Mission 2 would still include a crewed checkout of Orion’s systems in high-Earth orbit, a lunar flyby, and free return trajectory back to Earth. However, flying this mission on a Block 1 SLS would preclude a co-manifested payload that had been planned. NASA had not yet specified this payload for the first crewed flight, but it could have had a mass of up to nine tons. Without the Exploration Upper Stage, NASA will not be able to fly, in a single flight, crew members and pieces of a deep space gateway it hopes to build near the Moon in the 2020s.

Additionally, by continuing to fly the SLS rocket in its Block 1 configuration, NASA opens itself up to the criticism that its own heavy-lift rocket is not that much more powerful than commercial options available now or within a few years. Both SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket and Blue Origin’s New Glenn have a lift capability of about 50 tons to low Earth orbit. However, they cost only a tiny fraction of what the SLS will require to build and fly.