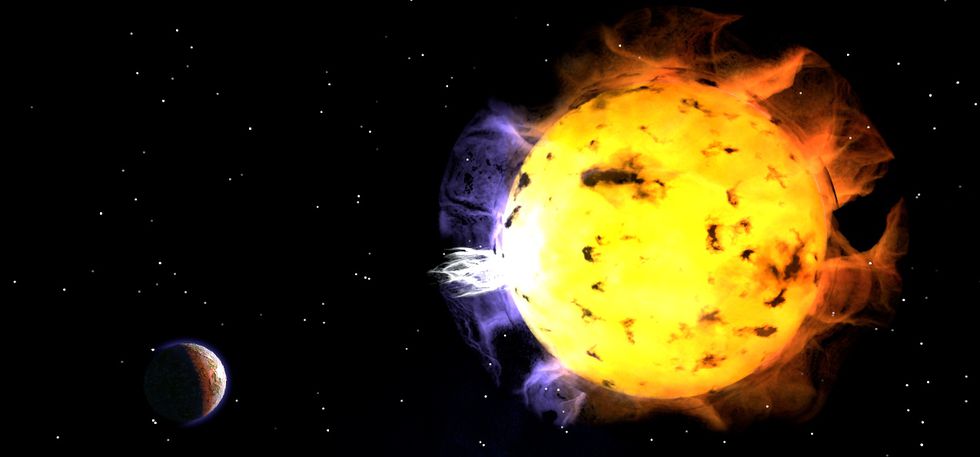

Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the sun, recently burst forth with one of the most powerful flares ever seen for a star its size. The small red dwarf is generally invisible to the human eye, but this flare may have lit it up bright enough for some naked eye observers to see the event—at least under the right conditions, according to Allison Youngblood, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

Youngblood and colleagues recently released a paper detailing the March 2016 event on ArXiv.org, a repository for scientific papers frequently used before studies are published in a journal. According to the team’s findings, the star brightened by a factor of 68 during the “superflare,” unleashing 316,227,766,000 petajoules (316,227 petawatts) of energy.

Proxima Centauri is just 4.2 light years away, but it’s a member of the smallest class of normal stars called red dwarfs, which only emit faint visible light. As such, it sits at magnitude 11—whereas the human eye can see magnitudes up to 6 or 7. (A low magnitude number indicates a high brightness, and some solar system objects are bright enough to dip into negative numbers on the scale.) The flare event placed the star at magnitude 6.8, which would have been as bright as a dim star on a clear, very dark night.

When the flare originally took place two years ago it was detected by the Evryscope, a nightly sky survey telescope that connects 24 consumer-grade camera lenses to look for transient events and transiting planets. The flare was 10 times more powerful than any ever witnessed from Proxima Centauri, which is already known for its quite volatile nature.

In fact, the superflare was so bright that an Evryscope algorithm normally used to find such events missed it on the first pass. “We estimate that flares of this size occur approximately five times a year on Proxima Centauri,” Youngblood says.

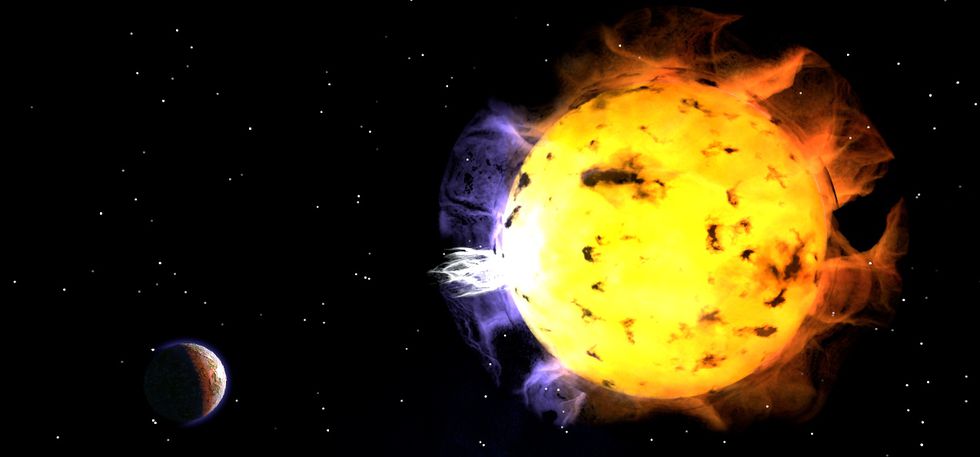

One potential problem with flares of this size is that Proxima Centauri has at least one planet and possibly more. The only confirmed planet in that system is slightly larger than Earth and in the habitable zone of its star—the region where planets under the right conditions can have stable liquid water.

While we don’t know much about the planet Proxima Centauri b, if you put Earth in its place, it would spell big, big trouble. The first hit from a flare of that magnitude would seemingly plant just a glancing blow, but chemical reactions would eventually weaken the planet’s ozone layer. From there, the prospect only gets more grim.

“We find that within 5 years, ozone is 90 percent depleted, and if the star continues flaring at the observed rate, the ozone will be completely gone after several hundred thousand years,” Youngblood says. “Then, if another one of these superflares comes along and there is no ozone protection, the UV radiation incident on the planet’s surface would kill even the most radiation-resistant organisms.”

Youngblood points out that their modeling assumes the flares from the star include powerful events called coronal mass ejections (CMEs), which would have a more destructive effect on a planet’s magnetic fields and ozone layer. Flare events around other stars aren’t well understood as of yet, especially for smaller stars like Proxima Centauri.

Even so, the Proxima flare was a rather potent event, and one that could spell doom for any otherwise-habitable worlds in the system. Most red dwarfs have violent, frequent flare events. They’re also the most plentiful stars in the Milky Way, and account for most known planets in habitable zones. That means that if Proxima Centauri b is cooked, similar planets may be just as doomed.