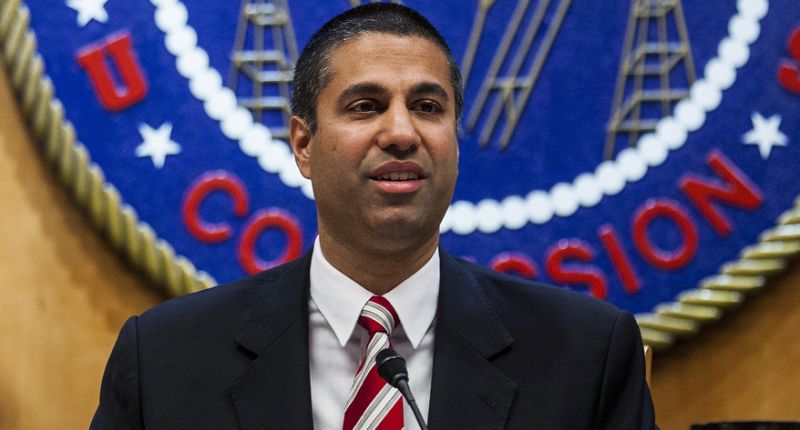

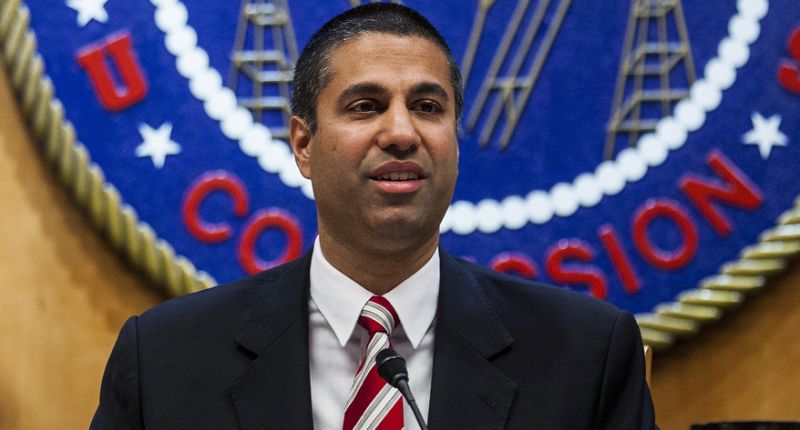

Federal Communications Commission chairman Ajit Pai just put a big item on his holiday wish list: having the FCC destroy the net-neutrality rules that it adopted two years ago.

As Pai said in a statement on the FCC’s site, he will have the commission vote at its Dec. 14 meeting on his “Restoring Internet Freedom Order.” The order would repeal what Pai called “heavy-handed, utility-style regulations” that ban internet providers from blocking or slowing legal sites or charging them for faster delivery of their data.

One of Pai’s colleagues responded almost immediately with a contrary, Thanksgiving-themed take. In a statement, commissioner Mignon Clyburn called Pai’s plan “a cornucopia full of rotten fruit, stale grains and wilted flowers topped off with a plate full of burnt turkey.”

But as Clyburn’s pithy protest noted, a 3-2 Republican majority now controls the FCC. Pai’s repeal plan, due to be released in detail Wednesday, will almost certainly pass.

And while the story certainly won’t end there, there will be plenty of lawsuits fighting the changes, Pai’s move could result mean an Internet of asterisks and dollar signs, where some sites are slower because they don’t pay your provider for priority delivery, while and others pass on those fees to you.

What’s Title II to you?

Pai, who President Trump picked to head the FCC, has never hidden his feelings toward net-neutrality rules championed by his Obama-appointed predecessor Tom Wheeler. He hates them, from their regulatory foundation on up.

In his statement, Pai said the current rules “depressed investment in building and expanding broadband networks and deterred innovation.”

But what he’s really talking about is less the reality of these rules — even under Wheeler, the FCC didn’t get beyond asking some internet providers to explain some “zero-rating” exemptions to their own data caps — than how they could be enforced under a future FCC.

That’s because when the FCC adopted the current regulations, it built them on a legal foundation dating to the 1934 law that created the agency. Title II of that law lets the commission regulate “common carrier” services — meaning ones anybody can sign up for — to ensure they treat everybody’s traffic equally.

So while Wheeler’s FCC voted to set aside Title II provisions allowing it to regulate prices, in theory a future president could put in a new commission that would bring down the heavy hand of the regulatory state.

Why would the FCC bother with this ancient Title II strategy? Because telecommunications firms beat the commission in court every time it tried crafting net-neutrality rules on laws written after the internet’s creation.

The last such suit was filed by Verizon (VZ), which now owns Yahoo Finance’s corporate parent.

Pai suggests that by scrapping Title II, we’ll return to the good old days of Clinton-era “light touch” regulation. But that’s not true: In the 1990s, the FCC not only regulated internet access under that provision but even required phone companies to open their digital-subscriber-line broadband to competitors.

This is really about choice and competition

In place of Title II, Pai would re-classify internet providers under a different branch of telecom law. That “Title I” affords the FCC much less authority but does, Pai said, let it “require Internet service providers to be transparent about their practices so that consumers can buy the service plan that’s best for them.”

In the best-case version of what comes next, Internet providers would spend money now spent on complying with net-neutrality regulations on expanding their networks.

But the head of one of the few firms independently building out gigabit fiber-optic service assessed his net-neutrality costs at zero. “Title II is not a burden in any way,” emailed Dane Jasper, CEO of the Bay Area firm Sonic.

In theory, some might collect extra revenue by charging sites like Netflix (NFLX) and Amazon (AMZN) for priority delivery.

But while those two firms can afford to pay up, they now have such gigantic reach in the market that media mogul Barry Diller scoffed at the idea any telecom firm could push them around in an appearance at a conference in San Francisco last week.

Pai and other opponents of net-neutrality rules also point to data showing lower telecom investment. But major individual firms like Comcast (CMCSA) and AT&T (T) have either kept on spending money or have pointed to lower expenses to build out their networks.

And the internet providers’ own reports to the FCC show progress in giving more Americans greater choices in broadband — even if 58% of us still had only one or zero providers offering meaningfully fast downloads of at least 25 megabits per second.

Up next: Send in the lawyers!

The consumer protection Pai would keep involves a hand-off: First internet providers must document if they block or slow any sites or charge others for paid prioritization, then the Federal Trade Commission could take action against cases of “unfair or deceptive” conduct. Then, statistically speaking, you couldn’t fire that provider anyway unless you could deal with a much slower connection.

And as you may have noticed from the sorry state of consumer privacy in America, the FTC can’t do much even when companies are open about lesser forms of misconduct.

A company must often do something egregious — think of Vizio tracking people’s TV-viewing habits without notice — to get a smackdown from the FTC.

First, though, Pai’s proposal has to survive its own inevitable dates in court. To begin, theAdministrative Procedure Act let people affected by a change in a federal rule challenge that as being arbitrary and capricious.

“We are looking at probably a year for the initial appeal and then another year to wrap up subsequent appeals,” emailed Harold Feld, senior vice president at Public Knowledge.

That easily takes this debate into the next election cycle, which will put in place a Congress that could confirm the FCC’s course or reverse it yet again. You will remember to ask candidates running to represent you about this, right?