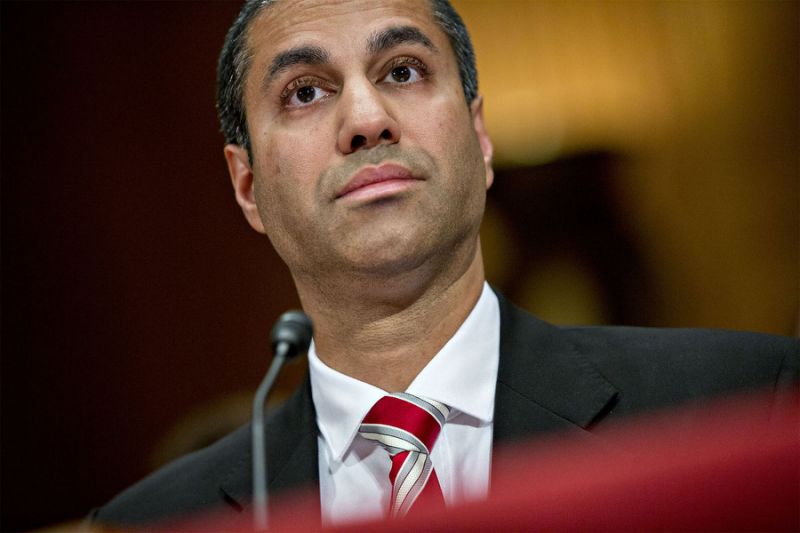

Federal Communications Commission chair Ajit Pai is adding yet another item to his to-do list. On top of cancelling broadband-privacy and net-neutrality rules, boosting rural broadband and battling robocalls, he wants to make media mergers easier.

In a post on the FCC’s site, Pai described this latest ambition as “modernizing our media ownership rules to reflect the marketplace of the present, not the past.”

Some of the anti-media-consolidation rules that President Trump’s choice to head the FCCwants to undo show their age in various ways. Others don’t. And one more sweeping part of this “modernization” agenda is yet to come.

The risk? Fewer choices for your news and entertainment that are more likely to be controlled by a giant, out-of-town conglomerate.

Who can buy what

For decades, the FCC has limited how many radio or TV stations any one person or company can own, both nationally and in a particular market. These caps have been loosened in various ways over the years, but the motion Pai wants the FCC to vote on at its November meetingwould relax them even further.

First, he would end a ban on newspapers owning radio or TV stations or vice versa in the same market, under the theory that online news sources provide plenty of competition for those traditional media outlets.

Second, he’d dump a rule limiting the combined number of TV and radio stations a company can own in one market, then lower the barrier to one firm owning two TV stations. If the FCC okays it, a single company could own two of the top four broadcasters in an area.

In its meeting this week, the commission took another step to making it easier to run a station remotely: It ended the 80-year-old “main studio rule” requiring a radio or TV broadcaster to have a studio near its listeners.

What will happen next?

The case for keeping the newspaper rule seems weaker. While TV still remains America’s dominant news source, the Pew Research Center found that as of August the internet was right behind it: 43% of survey respondents said they often get news online, versus 50% for TV.

But local news isn’t the same as news overall. “Television and daily newspapers are the principal forces shaping local opinion,” said Andrew Jay Schwartzman, a communications-law professor at Georgetown.

It’s also unclear that we’ll see newly-invigorated local media from combined print-and-broadcast operations like the mid-1970s incarnation of the Washington Post. More recently, two of the biggest media conglomerates have shed publishing or broadcast properties so that the two resulting companies can focus more closely on one medium.

In 2014, Tribune Media (TRCO) cut loose its publishing operations, which now do business under the woeful name of Tronc (TRNC). A year later, Gannett (GCI) cut loose its broadcast division as Tegna (TGNA).

Schwartzman expressed more concern about the TV-ownership rules, predicting that having the FCC make case-by-case judgments of new station purchases will pose no obstacle. “Ajit Pai has never met a waiver he didn’t like,” he said.

The precedent for this — the massive consolidation of radio stations that happened in the 1990s and left the airwaves sounding a lot more alike, and which didn’t unwind until a decade later — invites pessimism about the results.

“We certainly don’t gain more competing viewpoints from eliminating independent voices,” said Matt Wood, policy director at Free Press.

More media merger bait

Pai’s regulation-reduction agenda, however, doesn’t stop with Thursday’s announcements. The FCC is also due to revise rules about a media company’s nationwide reach, last increasedin 2003 to let one firm own stations that reach 39% of U.S. TV-viewing households.

In a conference call Thursday afternoon, a senior FCC official said the chairman was “definitely committed” to begin discussing a raise in that cap by the end of the year.

One company, Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. (SBGI), will easily exceed that 39% limit if it wins government approval of its proposal to buy Tribune Media Company. That proposed union has drawn some surprising opposition — not just from media-diversity advocates but also from some conservative voices.

The liberal opposition to Sinclair is easily understood. It has a history of imposing its politics on its stations — in 2004, it banned seven ABC affiliates it owned from airing a Nightline tribute to the 500-plus U.S. soldiers who had died in Iraq by then.

More recently, as comedian John Oliver lambasted in a July segment, it’s moved to require its stations to air political commentary that ranges from phony to creepy.

Unlikely allies

Conservative voices have also begun opposing the Sinclair merger. In a Washington Post op-ed, Newsmax Media CEO (and Trump confidant) Christopher Ruddy warned that this merger and other moves by Pai would “lead to a massive consolidation of stations and homogenization of news.”

A group set up to oppose the Sinclair deal, the Coalition to Save Local Media, features such improbable allies as the liberal group Common Cause and the Glenn Beck-founded The Blazenews network.

(Disclosure: For about a year, I wrote for a tech-policy blog sponsored by another coalition member, the Computer & Communications Industry Association.)

All this has the makings for a tech-policy debate outside the usual party lines. But will that deter Pai and his Republican allies on the FCC? The net-neutrality battle — the rules remain intact, but seem increasingly likely to be voted out by the of the year — suggests that Pai is not one to let bad publicity get in the way of fulfilling a long-sought, long-advertised goal.