Martin H. Simon/Bloomberg via Getty Images

- Mega-deal M&A transactions worth over $10 billion are surging back after a largely dormant first half off the year.

- Wall Street bankers say an improving global economy and confidence in the regulatory environment are playing a role.

- The looming threat of super-corporations like Amazon has many large companies evaluating whether they can be an end-game winner — and whether they need to strike a deal to get there.

Broadcom announced its $130 billion takeover intentions for Qualcomm. Disney was revealed to be discussing a bid for most of 20th Century Fox, a deal that could cost $40 billion. Asset manager Brookfield was reported to be in the early stages of a bid for shopping mall investor GGP, a $20 billion company.

All within the span of a week.

Not long before that, power companies Dynegy and Vistra completed an all-stock mergerworth more than $10 billion, and Rockwell Automation rejected a nearly $30 billion takeover bid from Emerson Electric.

Is the mega-deal back?

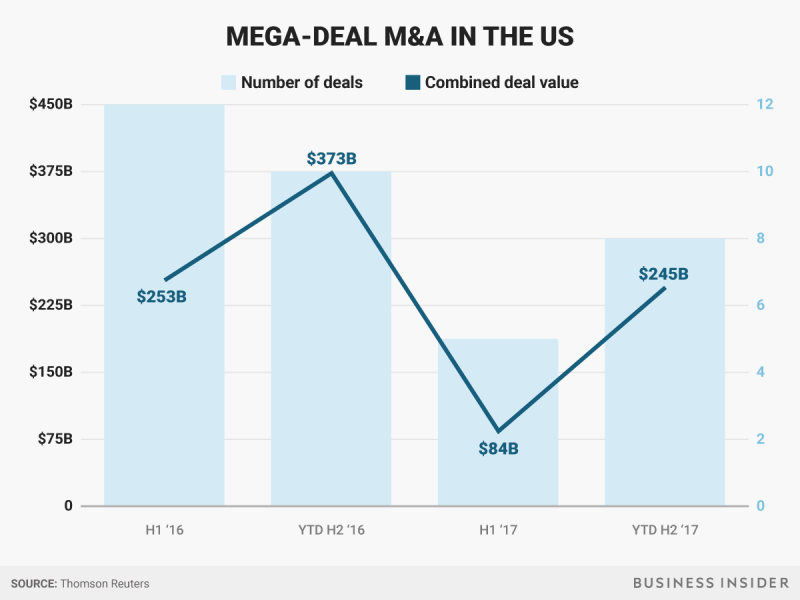

The year started off in a frigid climate for large mergers and acquisitions. Only five M&A transactions valued at north of $10 billion were announced in the first half of the year, with a combined transaction value of $84 billion, according to data compiled by Thomson Reuters.

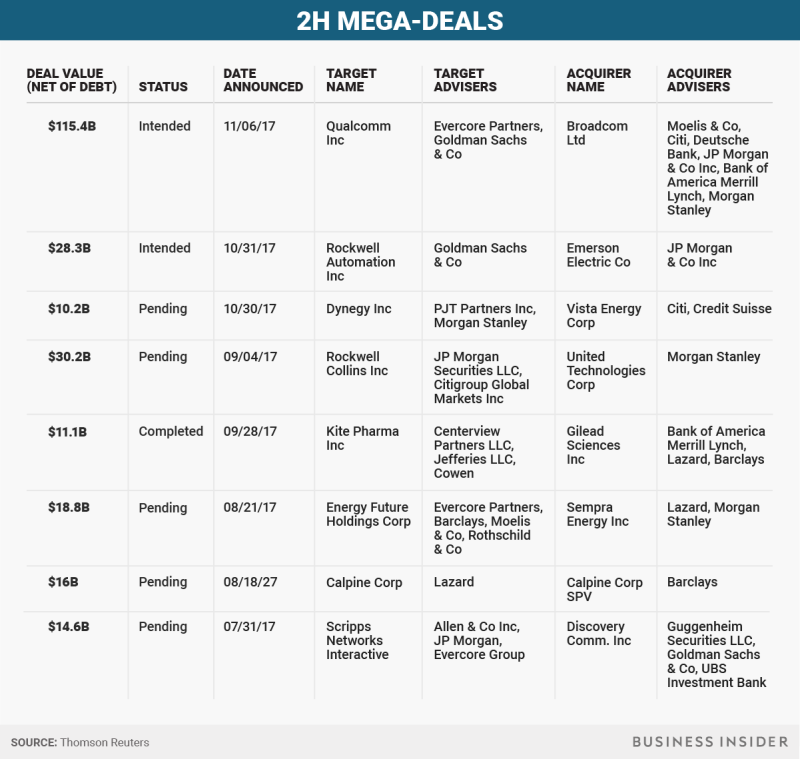

But corporate boardrooms of the US’ largest companies have worked up an appetite for mega-deals in the back half of 2017. Eight deals or attempted deals valued at more than $10 billion a piece — and a combined value of $245 billion — have been announced so far since July, already dwarfing the front half of the year with seven weeks yet to go.

While mega-deals are still well off the firecracker pace from recent years, the rebound of late is a sign of increasing confidence in global economic conditions and a favorable regulatory environment. But it also highlights the rapidly dawning realization that technological disruption poses an existential threat even to industry giants.

The specter of a global-super corporation like Amazon, Google, or Walmart entering a new industry at a whim has previously fearsome conglomerates with market capitalizations in the tens of billions feeling rather small and acknowledging that maintaining the status quo is now a risky bet.

Mike Nudelman/Business Insider

“If you’re not acting proactively, aggressively to evolve your business and change your business, you’re likely falling behind — and that realization is happening at a greater pace,” Chris Ventresca, global cohead of M&A at JPMorgan, told Business Insider. “Therefore, people are more willing to consider deals that they may not have considered in years past.”

The cool off

Why did mega-dealmaking cool off so much at the beginning of the year?

Small M&A activity — deals worth less than $10 billion — remained strong, with $490 billion across 6,900 transactions, according to Thomson Reuters. That eclipsed small-deal volume in the first half of 2015 and 2016.

It was the large deals that lagged behind.

One explanation for the hesitancy was the nascent administration of President Trump, who had made a habit after his election of tweet-shaming companies which made strategic moves that resulted in fewer jobs for hardworking Americans.

How would his regulators respond to large mergers that stood to benefit from synergies and cost cutting?

Such concerns began to ebb by summer. The President’s ability to smack stock prices with a single tweet quickly waned, and his social media salvos shifted focus toward more pressing concerns, such as the Russia investigation, the healthcare debate, and North Korea’s “Little Rocket Man.”

More importantly, big deals started to trickle through without arousing attention from the Department of Justice.

In April, medical devices company Beckton Dickinson bought surgical supplies manufacturer CR Bard for $24.2 billion. In June, Amazon sent tremors through corporate boardrooms when it swooped in to buy Whole Foods for $13.6 billion. In July, Discovery Communications announced a $14.6 billion takeover of fellow media company Scripps Networks Interactive.

The consolidations went uncontested, and more followed.

“Over the summer there was a number of big, strategic combinations and they didn’t seem to meet with a lot of regulatory or political resistance,” Mark McMaster, vice chairman of investment banking at Lazard, told Business Insider.

“It appears we’re in a regulatory environment where Washington is going to allow pure-play companies to continue to get larger,” he added.

The $85 billion merger between AT&T and Time Warner — announced in 2016 before Trump was elected — may be the exception, with regulators suggesting they’d file suit to block the deal. Reports have been mixed about whether the DoJ demanded the sale of Turner Broadcasting, the division that owns CNN.

Samantha Lee/Business Insider

By summer, CEOs also grew more confident that global economies were in sync and robust growth would continue.

With stock markets setting record highs and equity valuations soaring, this helped make the math on mergers more palatable.

Multiples may be elevated, but the premium is more justifiable with an upward sloping global economy.

“Things that may have felt expensive suddenly feel less expensive when you model in an improving global economy,” said Ventresca, noting that optimism on this front had improved from even six or nine months ago.

Deals also seem more palatable if a company can tap the low-interest debt markets or use their own inflated equity to finance a deal.

If companies swap shares in a deal, the fact that stock prices are inflated can be neutralized, McMaster noted.

The Amazon effect

Aside from giving investors and business leaders some confidence on the regulatory front, the Amazon takeover of Whole Foods more importantly served as a wake up call.

LazardGrocery stocks plummeted after the deal was announced, and pharmacy stocks took a hit as well.

Even large companies tens of billions in market capitalization began to confront the possibility that super-corporations like Amazon could wake up on a given day and upend their industry.

This forced firms to frankly assess their deficiencies and evaluate whether they have enough to be an end-game winner in their sector.

That’s why you’re seeing more mega-deals that establish a firmer footing within an industry.

That might be why Disney — facing threates from Netflix and Amazon — isn’t certain it can win purely by growing within. Acquiring 20th Century Fox would give them a major leg up. And CVS Health’s reported $66 billion takeover plans for Aetna has everything to do with staying one step ahead of Amazon.

“Companies are feeling the pressure of creating end-game winners within their various sectors and are willing to take a longer-term view of whether they have the pieces of the puzzle to be that end-game winner,” Ventresca said. “And they’re acknowledging that if they don’t, they might not have the luxury of time and building it on an organic, greenfield basis.”