-

Junta wants to create second Asian aircraft maintenance hub

-

Thailand investment board says FDI recovering from 2014 fall

Thailand is seeking to take on Singapore’s dominance in aircraft maintenance, repair and overhaul with a $5.7 billion upgrade of a Vietnam War-era airport.

Lockheed Martin Corp.’s Sikorsky Aircraft is the latest company to study a possible increase in MRO spend in Thailand in the wake of the planned revamp of U-Tapao International Airport, said Ajarin Pattanapanchai, deputy secretary general of the nation’s Board of Investment. In March, Airbus SE signed an agreement with Thai Airways International Pcl to evaluate the development of MRO facilities at the civil-military airport near Bangkok.

Top News: Bullfrog Gold Raises $816,000 Of Equity To Advance Its Nevada Gold Project

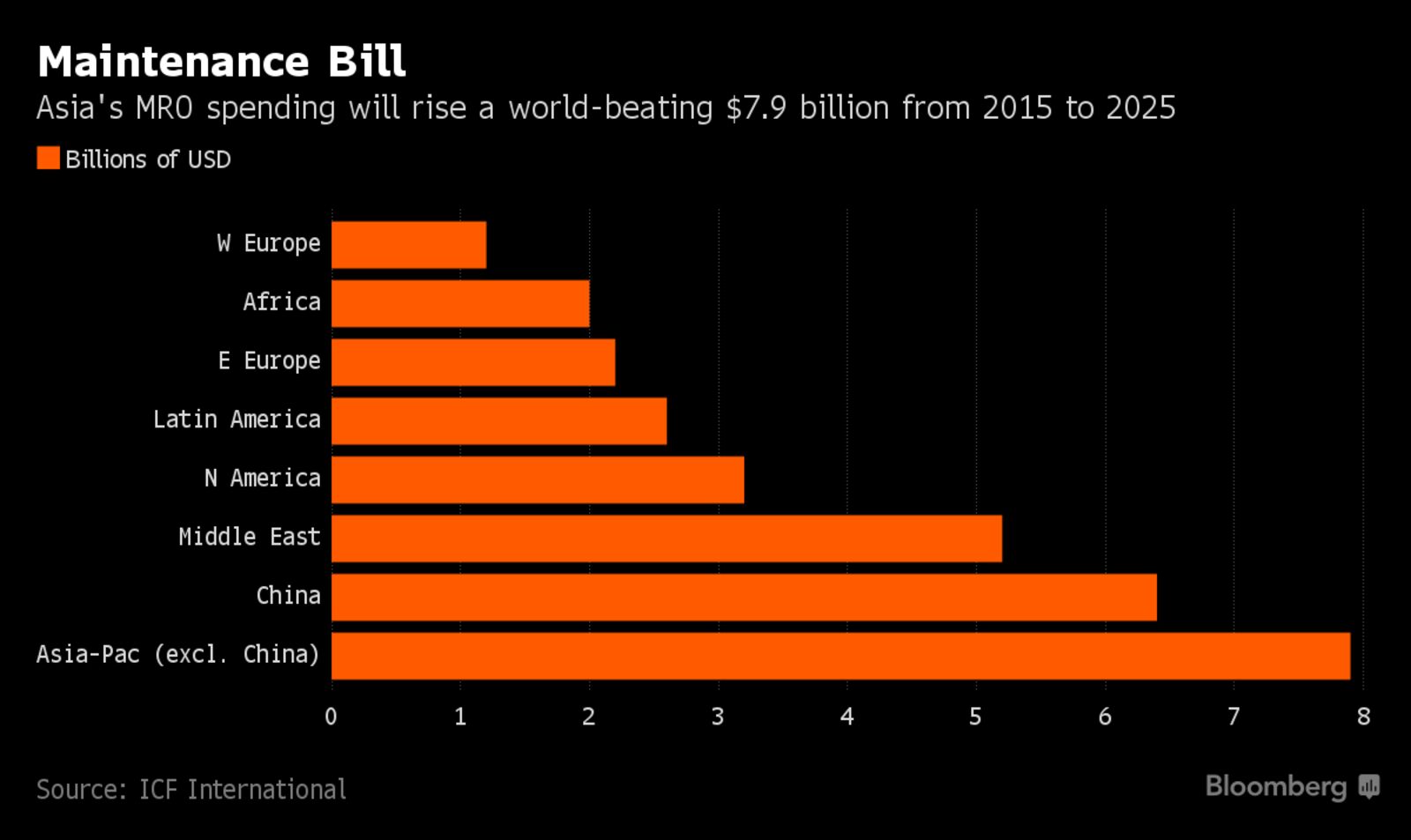

“Singapore is quite tight right now,” Ajarin said in an interview at Bloomberg’s Toronto office on May 25, during a visit to Canada to woo investment. “To catch up with the demand of airlines in the region — especially new demand from Myanmar, Vietnam, Cambodia — and given that we have existing strengths with automotives and engineering, Thailand will be the second choice to be the MRO hub.”

The airport project is part of junta leader Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-Ocha’s goal of boosting the economy, whose expansion has lagged behind neighbors since the military seized power three years ago. It’s also a key component of a plan to invest 1.5 trillion baht ($44 billion) between 2017-2021 to develop the country’s eastern seaboard.

Don’t Miss: Is This Tiny Gold Mining Company The Next Big Thing?

Apart from the airport in the Eastern Economic Corridor, the plan calls for $4.5 billion investment in high-speed rail, $11.5 billion for new cities and $14 billion for industry. The government will control and maintain the airport and a port. Other projects will be public-private-partnerships or privately held.

“I am confident we can make it,” Ajarin said, referring to raising the funds. The government has already allocated its budget for 2017, she said, declining to provide a figure for the administration’s outlay on the corridor or an estimate of the MRO business Thailand is targeting.

Foreign-direct investment has revived after sliding following the coup, especially in digital and high-technology sectors, Ajarin said.

She gave as an example Toronto-based Canadian Solar Inc., which applied for a license in 2015 and opened its Thai factory two years later. Among electric vehicles, a “big player — but not Tesla — is waiting to come in,” Ajarin said.

Also see: Is this the end to banking as we know it?

FDI increased to $8.6 billion in 2016 from $2.7 billion in 2015, according to data provided by the Board of Investment.

While the board offers incentives to foreign companies such as tax sops, it remains unclear how quickly the Thai government can implement its ambitious vision for the eastern seaboard given the scale of the project.

Challenges include a shortage of skilled workers, as well as concern that Thailand is prone to harmful episodes of political volatility.

Ajarin acknowledged that the risk of political turmoil is a worry for new investors, but argued that companies have weathered past such bouts.